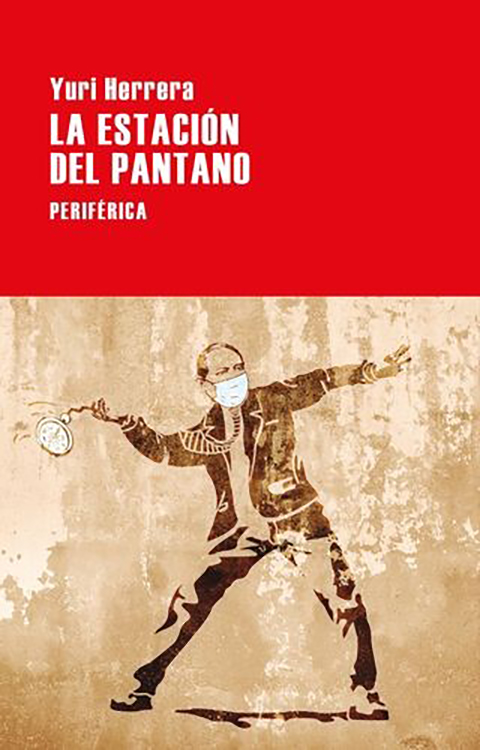

Cáceres: Editorial Periférica. 2022. 185 pages.

Yuri Herrera’s latest novel, La estación del pantano (Editorial Periférica, 2022), smells of coffee and tobacco leaves. We enter it like we might the shadow of one of Conrad’s boats, or a run-down tavern, drowned in a suffocating heat. From these deep, dense airs emanate more scents, humid and stagnant, that carry traces of blood, sweat, and history. They are the scents of hundreds of bales of cotton, harvested by Black slaves and stacked in the port of New Orleans in the mid-nineteenth-century, and of the many newspapers that shine like a palimpsest beneath the pages of this novel.

Yuri Herrera’s latest novel, La estación del pantano (Editorial Periférica, 2022), smells of coffee and tobacco leaves. We enter it like we might the shadow of one of Conrad’s boats, or a run-down tavern, drowned in a suffocating heat. From these deep, dense airs emanate more scents, humid and stagnant, that carry traces of blood, sweat, and history. They are the scents of hundreds of bales of cotton, harvested by Black slaves and stacked in the port of New Orleans in the mid-nineteenth-century, and of the many newspapers that shine like a palimpsest beneath the pages of this novel.

So it is, by layers of news clippings from the era’s press, of archival fragments, of letters, typefaces, and overlapping maps, that this spherical novel takes up volume, building its own world just as it reconstructs another: that of New Orleans between 1853 and 1855. Like in Señales que precederán al fin del mundo (Editorial Periférica, 2009; translated by Lisa Dillman as Signs Preceding the End of the World, And Other Stories, 2015), the reader follows, or perhaps pursues, a character in transit. That character is Benito Juárez, the future first indigenous president of México, and the journey is that of his exile, which begins in Cuba and ends in Louisiana.

Given that linear progression is not the model that usually defines voyages—and even less so, the works of Yuri Herrera—we can begin by saying that La estación del pantano chooses a path that is the antithesis of the travel narrative. As the title indicates, the novel recounts an unmoving itinerary, paralyzed by the secrecy of exile—a stagnation in a temporal and spatial layover that begins with the arrival of Juárez via mailboat at the port of New Orleans, and ends when he leaves, a year and a half later, also by boat, headed for Acapulco. In this interstice, in this crevice within History that the author infiltrates and rescues from the mired swamps of time, is this intimate history of Juárez’s New Orleans exile that he himself did not write and that the historical archive did not save. Let us call it an imaginary life, after Schwob, or an experiment with the suspension of time, as in Borges’s “El milagro secreto” or “La otra muerte”: La estación del pantano surmises an untold story and fills a “hueco marcado por el punto y aparte” [hole marked by the paragraph break], as the introductory note anticipates.

“ALMOST PHANTASMAL, LOST IN THOUGHT, BENITO JUÁREZ, WHOSE FACE THE NARRATOR NEVER LETS US SEE, IS WITNESS TO THESE DISCONCERTING SURROUNDINGS THAT HE OBSERVES OUTRAGED, CAUTIOUS, AND SILENT”

The fresco of this nineteenth-century city that emerges from the novel is the color of tobacco and stained, aged paper. Wandering through its streets are Juárez and his companions—among them Ponciano Arriaga, José María Mata, and Melchor Ocampo—remorselessly men, exiled and pursued Mexican politicians, in the middle of the local hubbub, of the excesses of drums, pianos, theaters, horse races, and the daily cruelties that surround them, in a turbid mess of whites and creoles, murderers and sailors, prostitutes and drunks, slaves and their owners. A diverse mix of languages, ethnicities, and races coexist in this complex geography: “blanco-blanco” [white-white] creoles, “blanqueados” [whitened] and Black creoles, and slaves, some on the plantation, others in the city. Blindly following or pursuing an unnamed character—who will turn out to be Juárez, but whose identity is withheld from us, keeping us guessing from beginning to end—we bear witness to the most sordid of urban meanderings. We even cross the threshold of one of the most blood-chilling sites in the entire country: the slave markets at Gravier, where cages and showrooms exhibit, “como ganado” [like cattle], many “manos sin persona” [personless hands]: slaves referred to only by the part of their body that provides the brutal labor of “pizcar algodón” [picking cotton] and “cortar caña” [cutting sugarcane].

Almost ghostlike, lost in thought, Benito Juárez, whose face the narrator never lets us see, is witness to these disconcerting surroundings that he observes outraged, cautious, and silent. He listens without speaking; he is surprised without remark, while, isolated and sentimental, he deciphers local English-language newspapers and devours those that occasionally arrive from México, which “a él no lo menciona[n] de nombre” [don’t mention him by name], and writes letters to consuls and mayors without being able to sign them, owing to the accusations of conspiracy weighed against him. Even worse, this humiliating silence to which he is condemned by dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna—who is responsible for his exile—is duplicated by another silence, which also isolates and frustrates him as a learned jurist and cultured politician, preventing him from intervening in the conversations and debates that spring up about him: English. This new tongue, which Juárez attempts to befriend over the course of months, continues to be a foreign and hostile language in which every word becomes “un bulto” [a bulk], an obstacle that imposes itself between him and the fluid discourse he could produce but does not succeed in relaying.

It’s only on the penultimate page on the novel, just when the swamped season of exile ends, that this spiral of silences is broken: on the gangway of the boat that will return him to México, Benito Juárez García introduces himself to the ticket seller with his true name and, for the first time, lets us hear his voice. Just as in that extraordinary epilogue to El hacedor (published in English as Dreamtigers), in which Borges imagines a man whose job it is to “dibujar el mundo” [draw the world] and who, “poco antes de morir, descubre que ese paciente laberinto de líneas” [shortly before dying, discovers that this patient labyrinth of lines] that he has been passing through for his whole life “traza la imagen de su cara” [traces the image of his face], each step that Juárez has been taking since his departure traces his destiny and his return trip to Mexican lands. But then, when the swamp layover is concluded, so is the novel.

The recovery of stories from muddied earth, and of voices from silence, like that which is buried, is the defining mark of La estación del pantano, just as it is for the author’s previous novel, El incendio de la mina El Bordo (Editorial Periférica, 2020; translated by Lisa Dillman as A Silent Fury: The El Bordo Mine Fire, And Other Stories, 2020). Both books lie over murky waters, clouds of smoke, judicial machineries, and residues of other stories cut short. By looking into the archive, Yuri Herrera digs up much earth and finds, in subterranean layers of the city, the mine and the swamp, stories that have been made invisible, be it from smoke or lack of air or from “la cuticula verde del patano“ [the green cuticle of the swamp] that covers lives and History in an opaque and motionless cloud. And even so, despite being submerged in the nineteenth century, the author continues inventing neologisms and shaping the Spanish language with his unique and unmistakable twist. In these gestures, the writer seems like that mythical bird, tattooed on the shoulder blade of the first men whom Juárez accidentally stumbles upon when disembarking in New Orleans and whose glyph appears drawn in the book. Yuri Herrera is like this bird, who walks forward but looks back, advancing without forgetting the past. So it is that once again he takes another of his characters into the light of History and returns to “mirar las estrellas otra vez” [look back at the stars again].