La derrota de lo real. Pablo Brescia. Miami: Librosampleados, 2017. 146 pages.

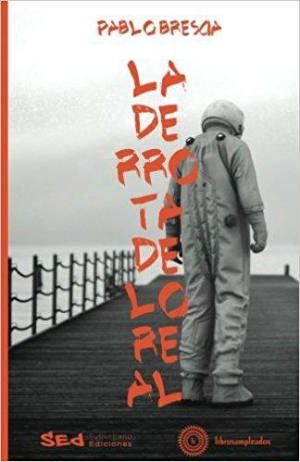

With La derrota de lo real [The Defeat of Reality], Pablo Brescia has chosen to bolster the notion of the book as a weapon, a sign of the symptomology of contemporary cultural malaise. The cover functions as the introduction to the threshold: the man facing away from the reader wearing a spacesuit is located in a limited frame. Both the man and the suit are symbols of resignation, underscored by his paralyzed body. At the same time, in his act of facing away, we recognize a line of escape between grey and greyer. It is not the visionary power of the marvelous or the fantastic, but the ability to see the ordinary details, particles and margins. Brescia suggests that we can only defeat reality by seeing it at its most vulgar levels. In its vocabulary, this task is like measuring the world’s absurd, contradictory and tension-ridden moments. This is how I understand the back cover: the author—Pablo Brescia—as a character; a man that looks on with transplanted eyes. The vision is reinforced when it comes to pass in the realm of the ordinary or familiar.

With La derrota de lo real [The Defeat of Reality], Pablo Brescia has chosen to bolster the notion of the book as a weapon, a sign of the symptomology of contemporary cultural malaise. The cover functions as the introduction to the threshold: the man facing away from the reader wearing a spacesuit is located in a limited frame. Both the man and the suit are symbols of resignation, underscored by his paralyzed body. At the same time, in his act of facing away, we recognize a line of escape between grey and greyer. It is not the visionary power of the marvelous or the fantastic, but the ability to see the ordinary details, particles and margins. Brescia suggests that we can only defeat reality by seeing it at its most vulgar levels. In its vocabulary, this task is like measuring the world’s absurd, contradictory and tension-ridden moments. This is how I understand the back cover: the author—Pablo Brescia—as a character; a man that looks on with transplanted eyes. The vision is reinforced when it comes to pass in the realm of the ordinary or familiar.

In those stories that give off a fantastical aura, it is always a minimal detail that marks vicissitudes and tensions. “Takj” and “Las que lloran” [The crying women] are connected to a Borgesian style, be it due to the creation of a distant sphere or a narrative form loaded with erudition. Nevertheless, Brescia harnesses the Borgesian impulse, configuring a system all his own. In “Takj,” the decisive factor will be the oversight of missing bloody footprints and the madness that buds from the effort to detain death. In “Las que lloran” the body is relevant to the attempts to deny pleasure only to search it out indefatigably by the protagonist, Rajiv. Different ways of feeling and moving the body alter reality through trips, divisions or excesses (such as the scene in which Rajiv is jacked off for three months by the men and women of his town).

Here, the material outwardly serves a worldly function. That is to say, reality arises through blood, sex, placenta and broken bodies (like Randy’s prosthesis in “El valor de la poesía”[The Value of Poetry]). Brescia perceives that reality can be abolished by more than the evocation of a supernatural beyond, as he did in his previous works. The power of creation is emphasized by the search for immanence. If Brescia used to translate invisible worlds, in accordance with a fantastical aesthetic, in La derrota de lo real he offers invisible bodies that are so very familiar today – mediocre heroes and distorted and racialized bodies. To this effect, “El valor de la poesía” results emblematic. Poetry is stripped of the aura of fine letters, from its world of aristos, and is pronounced from the body, from the repressed spaces and disabilities. For Brescia, the value of poetry is not found in the decoration of reality, but rather in discovering it in society and using it in concrete defenses. In this manner, the author pursues the notion of poetry driven by Enrique Fierro. Randy and the Uruguayo resist before that man with the suit and the black briefcase, the icon of liberal ideology. Their resistance comes not through speech, but through violence. La derrota de lo real thusly allows for the understanding of literature as the embrace of a political position capable of taking shape in actions, contagious affection and vital impulses.

For this very reason, the book loses some power in the metatextual stories that lean upon pictorial or literary references. Reality cannot be conquered with that which is “literary, too literary.” In this manner, “Gestos mímimos del arte” [The minimal expression of art] and “El señor de los velorios” [The funeral master] begin the second segment of the work, while “El resto es literatura” [The rest is literature] remains as an anecdotal exercise. Still, a confrontation appears in said segment between a sort of aestheticism (heavily criticized by Huidobro in the verses of Altazor – “Basta señora poesía bambina” [That is enough childish poetry, Madame]) and the demystification of literature. On one side, one chooses affectation and erudition; on the other, a critique of literature’s ostentatiousness or emptiness. Brescia chooses to confront the literary critic in “Pequeño Larousse de escritores idiotas” [Little Larousse for idiotic writers]. The narrator will take pleasure in unimportant facts, exaggerate in his judgment search a story from top to bottom, even though it be without either defenses or riches. This is where the Salvadoran critic is attacked (dixit Luiselli) who writes reviews like some people make churros. In one part in particular, he quotes Witold Arcé: “Escupe para abajo” [Spit downward]. The commentary that follows is vacuous and exaggerated: “los críticos destacan la crisis de la subjetividad y la búsqueda de la propia expresión” [critics highlight the crisis of subjectivity and the search for self-expression] (63).

Confronted with this model of Byzantine prose, Brescia bets on a soberer style. There is always a rhythm that sustains calm, even in the most pivotal moments. We are not exposed to explosions (the only exception is “Putas, Las Lenguas” [Whores, the tongues]), but to waits, concentrations that that are later unfolded as the author opts for sobriety. This style does not implicate diminished intensity, but a sense of regulation that aspires to greater depth and surprise. In this way, it begins “Un problema de difícil solución” [A problem with a difficult solution], where the quartering or the grotesque are told in a prose free of pathos: “Beso ese cráneo que ya casi no pertenece al cuerpo y le meto la lengua en una oreja. Creo advertir una mueca de placer. Me muevo despacio, me deslizo rítmicamente para llenarme de sangre, para que me sienta”; “Abro los ojos. Acaricio eso frío, mutilado, potente, que está debajo de mí. Enciendo otro cigarrillo, pero esta vez el gesto no es de nerviosismo, sino de descanso” [I kiss the head that barely hangs from its body and slide my tongue into an ear. I think I see a face of pleasure. I move slowly, stroking rhythmically to fill with blood, so it feels me”; “I open the eyes. I caress that cold, mutilated, powerful body beneath me. I light another cigarette; this one is for rest, not nerves] (18).

I ask myself whether the sobriety of the narrators is an expression of dormant sensibility in globalized times. Does Brescia articulate the style that I indicate as a way of emphasizing broken methods of feeling? There is a tendency to focus on broken realities, conditions of life controlled by hegemonic violence. That symptomology of the contemporary of which I was speaking tries to detect social problems and question acts of violence against female bodies (“Puta, o Las Lenguas”), or against immigrants in the United States (the impossibility of writing about Hispanics in New Jersey for Jonathan in “Melting Pot,” or Wilson’s xenophobic comments in “Código 51” [Code 51] – “Usted, comisario Torres, no deja de ser un mexicano de mierda ¿entiende? Esta no es su tierra ¿entiende? Hay que acabar uno por uno con ustedes, son como las cucarachas. Hay que limpiar esto, empezando por usted” [You, Commissioner Torres, do not cease to be a shitty Mexican, get it? This is not your home, get it? We have to get rid of you people one by one, just like cockroaches. We have to clean this up, starting with you] (114)).

Likewise, the reader perceives the necessity of analyzing a life reduced to capitalism. “Un día en la vida de Mr. Black” [A day in the life of Mr. Black] focuses upon the misfortunes of a fallen hero, a white trash icon, reduced to powerless, petty normalcy. Mr. Black’s efforts to carry out heroic acts do not only owe themselves to the fact that he will soon die. What he searches for, above all, is existence – becoming visible in a system that attributes him no value. In this sense, the idea of “being” is only possible through absorption by the rules of capitalism. This is what occurs in “Mr. White pierde y recupera” [Mr. White loses and recovers]. The protagonist uses a detachable penis at the opportune moments. That is to say, the body is undone during daily life, only whole during sex. This system-world fractures under a feeling of wretchedness, when the body recognizes itself not merely through the lenses of objectivity or asepsia, but through its most intimate parts. Another form of defeating reality, (along with the ideology that sustains it), is recognizing the worldly vulgarity of the body, its own dirtiness or limits. Mr. White manages to retrieve his detachable penis, but Ms. Lancaster, who tries to put on her Portable Vagina, “tira el aparato contra la pared sin pensarlo demasiado” [throws it against the wall without thinking very much about it] (127). Brescia reminds us that it is possible to confront the modus vivendi imposed upon us by capitalist globalization.

The greater the worldliness, the greater the firmness with which the author takes the position. Return to simplicity to dismount reality. The inaugural tale, “Un problema de difícil solución” announces in its first line: “Hay una historia” [There is a story] (15). Do not narrate from cosmopolitan fictions or from artistic stances; narrate from where you hit the ground. We return to the tensions of the cover: the man in the spacesuit is not in some galaxy; he trends upon reality, in an intimate “here” to enunciate, speak and criticize. In the story that closes the volume, “El valor de la poesía,” within a greying life, Randy’s dreams highlight his disability: the loss of a leg turned to concrete in the world of the story. However, only when liberation from resistance takes place, when poetry reaches intense imminence, will Randy’s dreams bring him fullness: he recovers his leg and laughs with his friend, the Uruguayo. In this manner, his affirmation of reality is greater without falling into negations or schemes. Reality is always defeated by the mundane, by the tiniest pieces, by interference. These barely perceptible experiences are, perhaps, the most honest display of the many dimensions of La derrota de lo real.

Christian Elguera

Translated by Michael Redzich