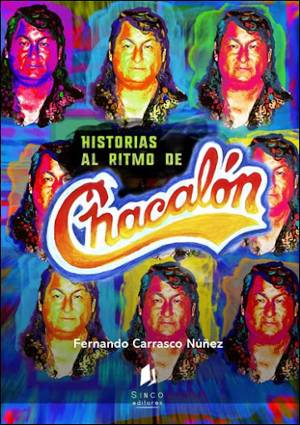

Historias al ritmo de Chacalón. Fernando Carrasco. Lima: SINCO Editores. 2020. 166 pages.

In his new short story collection Historias al ritmo de Chacalón [Stories to the rhythm of Chacalón] (Lima, 2020), Fernando Carrasco Núñez continues his exploration of topics connected to the criminal underworld. Carrasco is a storyteller who tackles such wide-ranging themes as death, betrayal, homesickness, and heartbreak, to name a few, but all from the perspective of marginalized subjects.

In his new short story collection Historias al ritmo de Chacalón [Stories to the rhythm of Chacalón] (Lima, 2020), Fernando Carrasco Núñez continues his exploration of topics connected to the criminal underworld. Carrasco is a storyteller who tackles such wide-ranging themes as death, betrayal, homesickness, and heartbreak, to name a few, but all from the perspective of marginalized subjects.

Given its title and its cover, the book could be mistaken for a tribute to Peruvian chicha music singer Lorenzo Palacios Quispe, better known as “Papá Chacalón.” However, it takes a different direction. For me, these stories evoked El llanto del ayaymama [The Ayaymama’s lament], Welmer Cárdenas Díaz’s novel that tells the story of the legendary Peruvian cumbia band Juaneco y su Combo. I read the first story, “Los Once Chavetas,” expecting to find Chacalón as a character, or at least a story set at one of his concerts. However, not Chacalón himself, but rather his music, is the most important element in Carrasco’s stories. The chicha’s melancholy lyrics are evident in the barrio’s revelries (“Los Once Chavetas”) and even inspire the characters’ lives (“Al ritmo de Chacalón”).

The dramatic monologue presented in the seven short stories that comprise Historias al ritmo de Chacalón not only silences the narrator—whose presence may be confused with that of the author himself—but also makes the characters responsible for telling their own stories. In this way, the author gives a voice to the voiceless. Carrasco’s characters live in extreme economic and moral poverty, as subjects who live in those areas of the capital that we prefer to avoid. Characters such as Chaveta, Chatín, and Metralleta make us cross the street to avoid them or hide our belongings. However, in his narrative world, Carrasco manages to make us follow these subjects, to see what they will do or what decisions they will make.

In the middle of the second story, “Carehuaco,” I couldn’t stop wondering if the book was conceived as a way of experimenting with dramatic monologues as a literary device, with the stories merely serving as excuses for trying out this stylistic tool. I think the empathy we readers manage to feel for Carrasco’s “forgotten” characters couldn’t have been achieved if he had used an omniscient narrator or another narrative technique. Using the monologue lets us get to know the characters’ essences: their way of speaking, thinking, and feeling. However, its use is neither merely aesthetic nor a simple strategy for hooking the reader or making the characters more believable. The use of dramatic monologue in Historias al ritmo de Chacalón is a political action. And what action could be more political than giving a voice to those who lack it, and lending humanity to those whom society has robbed of their dignity and their rights? Fernando Carrasco manages to make the reader question the very values of Peru’s privileged class, whose members view poverty and marginalization as a personal choice and success as merely a question of will. Through the characters’ own words we become conscious of the ways in which society as a whole, with its laws, dynamics, and injustices, decides the course of our lives.

This dynamic narrative in which the writer mutes his own voice, but not his presence, begins to take shape with the first story (“Los Once Chavetas”) and is the book’s hallmark, although some of its stories are not narrated entirely by their own protagonists. In “Robacarros” [Car thief], a taxi driver tells the story of his son’s accident, which led the driver to commit criminal acts in order to pay the medical bills. In this story the protagonist’s voice alternates with that of an omniscient narrator. In “El retorno de Carmela” [Carmela’s return], a girl recounts the problems alcoholism brought her and how she managed to overcome her addiction. This story moves between first and second person: Carmela tells her own story to a professor in a writing workshop (first person), and, in turn, the protagonist’s conscience makes itself heard as she remembers and reflects upon her struggles with alcoholism (second person).

Fernando Carrasco gives us a new look at Lima, shows us marginalized subjects’ humanity, and manages to show us how to understand the life stories of those who frighten us. However, he has done more than give us stories and perspectives on how life is lived in the slums. With Historias al ritmo de Chacalón, the author succeeds in reflecting on his own role as a narrator. The writer positions himself, more than as one who seeks stories, as a listener, one for whom the best stories are real and who knows that the best way of telling them is through the words of those who have lived through them. With this book, the author succeeds in making us reflect on the borders between fiction and reality. As readers, we have doubts as to whether these stories happened in the ways Chaveta or Carehuaco tells them, yet we also recognize that Carrasco has reshaped, invented, and crafted his style in order to keep the reader’s attention and immerse us in these areas of Lima.

Abraham Vargas Bautista

Translated by Karen Martin