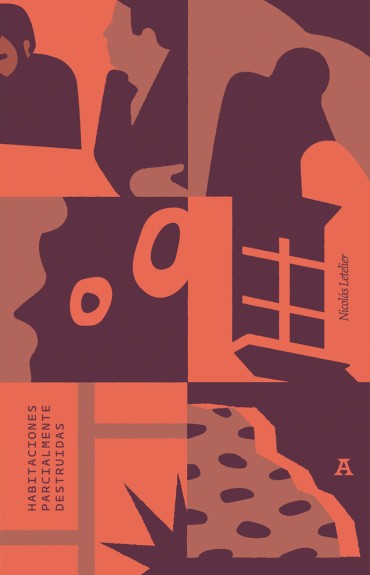

Arica: Editorial Aparte. 2023. 44 pages.

In his fourth book of poems, Habitaciones parcialmente destruidas (Editorial Aparte 2023), Nicolás Letelier Saelzer takes on the allegory of language as a prison house, always with irony, subtlety, and dissonance. The “prison house” of language refers to the idea and image employed by Friedrich Nietzsche of words as a constitutive condition of thought. This means language is familiar to us, while it also determines us.

In his fourth book of poems, Habitaciones parcialmente destruidas (Editorial Aparte 2023), Nicolás Letelier Saelzer takes on the allegory of language as a prison house, always with irony, subtlety, and dissonance. The “prison house” of language refers to the idea and image employed by Friedrich Nietzsche of words as a constitutive condition of thought. This means language is familiar to us, while it also determines us.

Two dramatic monologues, of different styles in terms of register and versification, open the collection of poems. “Dramatic monologue” is understood to be a rhetorical mode or lyric subgenre capable of evoking the speaker’s temperament from their most private thoughts. The first poem, “Of the Middle Middle Class,” probes into the euphemistic nature of this social category from a place of anonymous subjectivity: “work / produce / maintain / this / throng / of luminaries / who / live / in / all / this / that / is / beautiful.”The second poem, “Charles Robert Darwin / (1809-1882),” interweaves Chilean registers and modern allusions with the mindset of a high bourgeois Victorian character: “Modest as I am / I wrote the most elegant / treatise on ethics / more elegant than / Duke Ellington / but the scatterbrains / from here don’t understand / anything.” In both texts, irony constitutes a core resource for casting doubt on the speakers’ assertions and the motivation for social mobility.

As its epigraph (“From Paul Klee and Gordon Matta-Clark”) indicates, the title poem of the book uses ekphrasis, understood as the verbal representation of a visual representation, but which, through an exercise of imagination, is capable of emulating, translating, and questioning the compositional patterns employed by both artists. In the manner of Matta-Clark and Paul Klee, the poem seems to “perforate and intersperse” phrases and images related to language with lines and figures from the realm of construction: “cement reinforced concrete of organic forms / relations between what is said and what is projected what is wanted.” As this excerpt reveals, the principle of juxtaposition, taken up later in the sentence “all that is left is to superimpose,” falls not only between the verses but also within their interstices by means of the radical, but meditated, suppression of connectors and conjunctions. Thus, the processes of enjambment and superimposition crumble the foundations of language, where the poetic image, that “hologram of the mind,” acts as a cognitive projection, influenced by the work of Paul Klee and Matta-Clark. Based on such poetics, Letelier conceives of the poem as a partially destroyed room, belonging to the prison house of language.

“If language is that which ‘domesticates’ us, then the poem is responsible for denaturalizing and partially destroying everyday speech”

If dramatic monologues explore the rhetorical possibilities of irony, defined in a literal sense as the formulation of an opposite meaning, the poem “And” contemplates the difference between false and true statements. With elegant audacity, the speaker interrogates the true quality of “each sentence” and “each word.” For the subject, language lies not precisely because of the referent (“it is not the dog”), the signifiers used (“the vocalized sound”) or the non-verbal expressions (“here the / arm holds points at a / dog”), but rather due to the social character of everyday speech, which is capable of naturalizing its uses and conventions: “it is only sound that / we domesticate with word.” Therefore, if language is that which domesticates us (and here is the double meaning with the initial reference to the dog), then the poem is responsible for denaturalizing and partially destroying everyday speech.

The use of enjambment, consistent and extended throughout the collection of poems, disrupts the tension between rhythm and syntax, while reinforcing a metaliterary meditation on the process of poetic composition. In “Balcones II / Vanitas MMXX,” the speaker reflects on the creation and reception of an everyday event (“It is a nice gesture to intone / a song in the morning”), where the aesthetic pleasure resides not only in harmony, but also in dissonance: “and find beauty / not only in the melodic / lines that overwhelm / the brain and enjoy the / offbeats and basses.” In these last two lines, the enjambment is able to break the syntactic link established in the phrase by separating the article (“the”) from the noun (“offbeats”). In this way, the enjambment embodies the syncopated rhythm articulated by the speaker.

The variety of rhetorical modes in Habitaciones parcialmente destruidas is proof of Nicolás Letelier’s enduring craft and the intertextual fabric of his literary work, while demonstrating the poetic possibilities underlying everyday speech from an ironic, reflective, and skeptical lens regarding its means of expression. In the face of the prison house of language, the poem becomes not a construction site, but rather an occupied ruin.

Translated by Whitni Battle