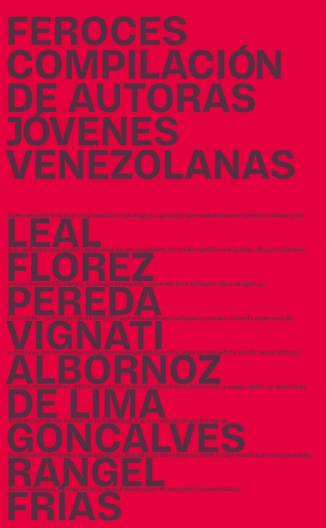

Venezuela: Sello Cultural. 2023.

The book Feroces brings together stories that aim to destabilize what is considered feminine, tales that show a wound, reactive stories that pose questions. Compiled by Jacobo Villalobos, designed by Juan Mecerón, and edited by Luza Medina, Tibisay Guerra, and María Esther Almao, the collection brings together work by Venezuelan authors Andrea Leal, Verónica Flórez, Sofía Pereda, Gabriela Vignati, Verónica Albornoz, Clara De Lima, Yoselin Goncalves, Natasha Rangel, and Ana Cristina Frías. Themes like the legacy of matrilineal tradition in interesting dialogue and contrast with the subversive and challenges to the status quo; sexual awakening and the discovery of pleasure; different forms of peripheries and minorities; and issues of identity, gender roles, and gender violence all undulate, permeate the pages, and bring the authors together. Each one is autonomous in her voice and accompanies the others.

The book Feroces brings together stories that aim to destabilize what is considered feminine, tales that show a wound, reactive stories that pose questions. Compiled by Jacobo Villalobos, designed by Juan Mecerón, and edited by Luza Medina, Tibisay Guerra, and María Esther Almao, the collection brings together work by Venezuelan authors Andrea Leal, Verónica Flórez, Sofía Pereda, Gabriela Vignati, Verónica Albornoz, Clara De Lima, Yoselin Goncalves, Natasha Rangel, and Ana Cristina Frías. Themes like the legacy of matrilineal tradition in interesting dialogue and contrast with the subversive and challenges to the status quo; sexual awakening and the discovery of pleasure; different forms of peripheries and minorities; and issues of identity, gender roles, and gender violence all undulate, permeate the pages, and bring the authors together. Each one is autonomous in her voice and accompanies the others.

According to Simone de Beauvoir, a specifically feminine discourse does not exist. For her, the authentic author is someone who universalizes the individual, who opposes the notion that women write about different things to men, or the very idea of women’s writing. Nonetheless, she notes that we women do tell particular stories, and we do so in response to the weight of historical oppression that we still carry. It is our way of saying, “I exist.” And of rebelling. Stories like those in Feroces think through what is silenced, create spaces for discussion, companionship, and taking a stand. Whatever form it takes, literature does not owe anything to anyone, you write what you must write; the what and the how is something the author comes to through searching for her own voice, starting with the spice rack, the toolbox, the baggage of materials that infiltrate the page or the screen and go beyond gender.

Every time a female author puts a foot outside of what “the feminine” supposedly is or should be, she challenges the established order. Citing a poem by Patmore, in a speech to The Workers Society, Virginia Woolf referred to the day when she realized that, unless she killed the angel in the house, that vision of the feminine as angelic, sweet, complacent, and self-sacrificing, she would never write literary criticism, or anything really. Killing the angel in the house requires observing with distance, standing firm, declaring a position, and, yes, being ferocious.

Writing independently, not owing anyone anything, about or out of dissatisfaction, rage, sadness, desire, and against control, prejudice, and expectations, is only possible if we stay alert: the angel of the house is a spirit, it does not die, it lives evasively, lying in wait. Given that the feminine has been supposed to oblige the masculine, a female author who freely exercises her literary labor ends up being ferocious.

“If every compilation is a floor and a ceiling, support and shelter, this book is a protected place for free movement”

“Smart,” by Ana Cristina Frías, is a story about migration, keeping one another company online, the diasporic experience, an ethnography from Miami in which a woman tired of obliging, agreeing, and keeping quiet puts an end to her exploitation. In the story “Las piedras,” by Sofia Pereda, magic, eroticism, imagination, and different planes of reality hold hands with brilliant impudence, and desire is a central element. Andrea Leal, in “La Ninfa de Villa Ruselli,” joins the fantastic with the dark, the forbidden; a woman with a supernatural vagina who drives mad the uninitiated young man who, from repeatedly asking, obtains what he desires, finding himself faced with a forest. In “Maizales,” Verónica Flórez recounts a furtive encounter at nightfall which, in that liminal moment, leaves behind an enigma to solve. Magic—the hinge between night and day—breathes in every paragraph of the story. Gabriela Vignati also crosses through the mirror in “Casa de muñecas”: in her new job as a companion and domestic helper in a house with interchangeable doors, the protagonist loses her autonomy, becoming another doll in her employer’s collection. In “Cambio de fase o cómo corromper a tu prima,” Verónica Albornoz imagines a community with no men, controlled by the older women, in which pleasure is taboo and there is minimal freedom of choice; only those who have decided to procreate have the right to visit the city. Eroticism, masturbation and sexual awakening are the other conveyor belt. In

“No es un caracol gigante africano,” Clara de Lima approaches posthumanism and the supernatural, building a bridge between species. In the story, a body assumed to be defective risks physical or symbolic elimination. For her part, Yoselin Goncalves writes in “La bruja nos trae de vuelta” about sickness as both possibility and passage to the other side, to the invisible. She shifts from the everyday to the magical; the ungraspable and inexplicable is just around the corner. Finally, in “Jaula para zorros,” Natasha Rangel writes about twins who identify with each other in their desire, blood as an inheritance and fervor, in a story in which the uncanny—what is familiar and at the same time terrifyingly unknown—questions the border between genders.

The anthology Feroces connects with the idea of a global Venezuelan literature, with a diaspora aesthetics, in the words of Alirio Fernández Rodríguez, and with a certain way of producing, reading, and circulating texts that cannot be separated from the national crisis. A phenomenon that Gustavo Guerrero has called Venezuelan diasporic literature, which offers an opportunity for exchange and cultural projection. If every compilation is a floor and a ceiling, support and shelter, this book is a protected place for free movement. It is a house to which you return no matter where your body resides, because you write with what you carry on your back, with your language and the cultural weight of that language, tradition, and a way of being and doing things, references, smells, tragedies, and the party that marks the point of departure that will always be an anchor.

Writing goes beyond your current circumstances; it does not require one circumstance or another to appear. People write because they have no choice, because writing is their voice, their lungs and their heartbeat, the way to find themselves, to discover who they are and to prick readers with their words and wake them up. As Gloria Anzaldúa says in Borderlands:

Why am I compelled to write?… Because the world I create in the writing compensates for what the real world does not give me. By writing I put order in the world, give it a handle so I can grasp it. I write because life does not appease my appetites and anger… To become more intimate with myself and you. To discover myself, to preserve myself, to make myself, to achieve self-autonomy. To dispel the myths that I am a mad prophet or a poor suffering soul. To convince myself that I am worthy and that what I have to say is not a pile of shit… Finally I write because I’m scared of writing, but I’m more scared of not writing.

The authors of Feroces seek to create with this anthology their own cartography, to disorder what needs to be questioned so they can try to reorder it, to find autonomy, their own voice and a shared and free space. They accompany each other and accompany us.

Translated by Katie Brown