elis o teoría de la distancia. Lucas Margarit. Buenos Aires: El Suri Porfiado, 2020. 50 pages.

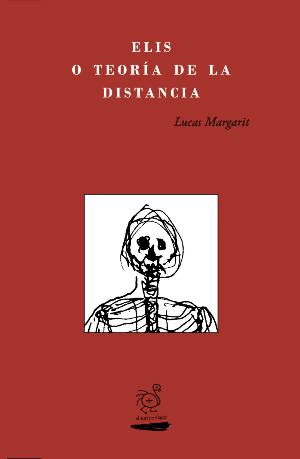

Inevitably, when one first sees the simple-yet-macabre front cover of Lucas Margarit’s new verse collection elis o teoría de la distancia [elis or theory of distance], one asks oneself: “Who is this Elis?” The book’s epigraph mentions Elis by name, citing a poem by Austrian poet Georg Trakl—a tragic figure from a family of musicians who died of a cocaine overdose in 1914, shellshocked in the trenches of the First World War. Trakl’s reference to Elis can be traced back to the story “The Mines of Falun” by E.T.A. Hoffmann, in which Elis is a man figuratively trapped in the breach between the real and the impossible, and literally trapped in a haunted mine.

Inevitably, when one first sees the simple-yet-macabre front cover of Lucas Margarit’s new verse collection elis o teoría de la distancia [elis or theory of distance], one asks oneself: “Who is this Elis?” The book’s epigraph mentions Elis by name, citing a poem by Austrian poet Georg Trakl—a tragic figure from a family of musicians who died of a cocaine overdose in 1914, shellshocked in the trenches of the First World War. Trakl’s reference to Elis can be traced back to the story “The Mines of Falun” by E.T.A. Hoffmann, in which Elis is a man figuratively trapped in the breach between the real and the impossible, and literally trapped in a haunted mine.

More specifically, and more importantly, Hoffmann’s Elis is preserved immutable in said mine, emerging decades later to re-encounter his now aged bride-to-be and disintegrate in her arms. Two of Trakl’s poems make direct reference to this tale; Margarit’s epigraph comes from the one titled “To the Boy, Elis,” which Margarit cites in Italian, English, French, Catalan, two translations into Spanish, and the original German. In Trakl’s troubled hands, the living-dead Elis serves as a simultaneous observer and embodiment of the expressionistic world around him. The blurred figure of Elis and Trakl’s weighty evocations of the natural world bleed together into one; a glimmer of Hoffmann’s folkloric character remains in this ghostly entity (“A thornbush chimes / where your mooning eyes are. / O, how long Elis, are you dead?”). And yet, this Elis has drifted radically away from his source material. Trakl turns Hoffmann’s tragic captive into a pervasive, ethereal presence.

Margarit takes another step in turn. As Dolores Etchecopar states in her brief introduction, his Elis is not Elis but elis, “written in lowercase: elis, as if it were not a proper name but a multiplicitous pronoun, changing according to the distance that calls him into question.” She is right to point out that, poetically as well as orthographically, Margarit’s elis is further distanced from his antecedents—elis is no longer a character so much as a center of gravity, the “conductor of a current of words that circulates through the landscape.” Margarit’s elis is Adamic: not content to haunt and be haunted by the natural world, he conceives of (or perhaps just conceives) the earth, as if he were made of it or it of him, not that both cannot be true at once.

“The Mines of Falun,” the 1819 story where Elis was born, is a distinctly elemental tale. Its sailor-cum-miner protagonist must choose between a life at sea, with all the openness and emptiness this entails, and a life spent below ground, not beyond but rather within the land, in a claustrophobic space of geological marvels unimagined by those of us who walk the surface. Hoffmann’s story, like many by the writer who inspired Freud’s formulation of Das Unheimlich, is also oneiric in both form and substance—its main character sleeps an impossible sleep in the mines, and the text itself smacks of a dream in its evocation of supernatural subterranean landscapes and its assignation of semantic importance to the smallest details of the natural world.

Margarit’s poems are similarly elemental, and similarly dreamlike. He presents an accelerating, interconnected sequence of scenes linked by motifs, many of which consist of the very natural elements both perceived and conceived by his elis: birds, stones, water, trees; a dark, wet, wooded landscape, unfurled in verse. These images guide the reader through the poems, growing familiar in the mind while simultaneously shifting through unexpected shades of meaning, taking on semantic weight as the poems progress. The overall impression is one of a cohesive world distinct to this poetry, and of an effort at worldbuilding accomplished in these pages.

That being said, the most important motif in this constructed world—the one that lies at its consciously hollow center—is one not of presence but of absence. The metaphysical questioning of distance is truly the book’s central concern, as its secondary title suggests. Is distance literally the empty space from one point to another, or rather a question of who measures said space? Here, distance—like stones, trees, and birds—becomes anything but literal. “The vastest distance of a point / is who observes it,” we read in “second dialogue.” In this sense, distance is simultaneously infinite and nonexistent, capable of taking on many forms depending on the figurative needs of the moment and differing from perspective to perspective: as we hear in “the pathways of elis,” “an animal sees distance / as another veil / the steppe repeats.”

Finally, returning to Dolores Etchecopar’s idea of “elis” as a pronoun, I should like to close with a final revelation surrounding this figure—one that is both grammatical and thematic. In Margarit’s book, elis does indeed serve in a universalized role as a sort of cosmic avatar through which the world is presented and designed. However, elis is not entirely depersonalized: in fact, elis appears alongside a small but significant cast of other pronouns (“you” and “I” stand out most starkly) that put his nebulous figure in contact with other human beings. This contact is sensual, erotic, corporeal; we read in one section of “distance or the rest”: “on my back your beard / slides and pauses / is modified / my body no longer implores / it plunges blind into / the images of a bloodless / sacrifice.”

Perhaps my favorite feature of this book is that, for all its cosmicism and its birds-eye view of a comprehensive world, it is also very much about the body—a human body in skeletal form, like the one we see on the cover—not figurative but feeling, still eager to be touched across the distance.

Arthur Malcolm Dixon