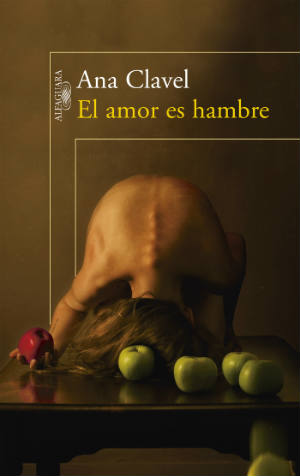

El amor es hambre. Ana Clavel. Mexico City: Alfaguara. 2015. 162 pages.

El amor es hambre. Ana Clavel. Mexico City: Alfaguara. 2015. 162 pages.

Upon reading Ana Clavel’s novel El amor es hambre [Love is hunger] (2015), the memory of any reader interested in erotic fiction will refer back to texts by Caribbean writers like Zoé Valdéz and Mayra Montero—that’s what the first few pages suggest, at least. But then we realize that Ana Clavel’s eroticism is not eroticism per se, but rather something veiled, something suggested, more in the vein of Luisa Valenzuela or Ana María Shua. Only later do we stumble upon the realization that this novel, for all it owes to the aforementioned authors, relies on a dynamic directed more by the spaces of possibility than by description. It’s important to mention that the novel also explores the currents discovered by Laura Esquivel in Como agua para chocolate [Like Water for Chocolate], just as the protagonist discovers her desires, in part, through her sense of taste, as Freud would have suggested.

The story is told in the first person by a narrator who takes us by the hand through the course of her life: from her birth, passing through the loss of her parents in an accident, leading to her adult life and her success as an international chef. The protagonist tells the stories of her many romantic adventures, but she does so in a way that is not direct but rather suggestive; for the narrator, the senses and their possibilities hold a place of privilege above purely sexual action and description.

The well-known children’s story of Little Red Riding Hood runs alongside El amor es hambre, and the relationship carries over from the book’s title to the protagonist’s life, over the course of her career, as she experiences love with various partners. Finally, it is platonic love with Rodolfo, her adoptive father, that makes her feel complete as a woman. The closest connection between the two is attained at the end of the novel, with Rodolfo in a hospital bed after open-heart surgery: “I hold your hands between mine and I kiss them. In India, there is a sect whose members eat their dead because they think they can find no better burial ground than their own bodies. I tell him that. Rodolfo smiles. Well, I’d eat you all up… he confides in me. I’d be satisfied with just a piece of you… […] I tell him, stroking his chest where the stitches from his operation form a sinuous path that I trace with my lips and my tongue” (157). This is the scene that encapsulates the novel; the relationship is suggested, as are all elements of the story, but the text intends for its readers to decide what happens for themselves.

The novel is made up of 46 short sections—almost chapters—along with four informative notes at the end of the text and a page and a half of acknowledgments. It also includes an invitation to the author’s website, where visitors can watch the video El amor es hambre/Corazón de lobo [Love is hunger/Heart of a wolf]. In this sense, the text and the video make an effort to establish interaction between the text and the reader. In my opinion, the relationship between the two is rather strained, since the images in the video—beyond being photographs of a model emulating Little Red Riding Hood—bear little connection to the text. Perhaps it’s worth pointing out that the photographs were taken in a forest, and the forest is a constant motif in the novel; also, a few phrases from the book appear alongside the photos. At any rate, the experiment’s intention is appreciable.

Laura Esquivel attempted something similar a few years ago with her novel La ley del amor [The law of love], which included a compact disc with instructions such that the reader could listen to the appropriate tune while reading the corresponding scene in the novel. For this reader, that attempt was a failure. Ana Clavel’s novel avoids this fate. It is attractive insofar as it does not abandon the suggestive; it doesn’t fall into the facile strategy of describing sex as a palliative to sustain the reader’s interest. Instead, it seeks to make the reader’s own mental games the decisive factor in all of its scenes, and that, to my mind, is its greatest merit.

Besides the video, the novel includes seven photographs among its pages: two of carnivorous flowers (which serve to represent the protagonist’s nature), one of Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf in bed, one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, one of the Fountain of the Fallen Angel in Madrid, and two more of the author herself (copied from the dust cover). The existence of the first five photographs can be understood, perhaps, through the relationship they hold with the text on the pages in which they appear; the inclusion of the author’s portraits, on the other hand, is beyond the comprehension of this reader…but maybe that’s the idea.

José Juan Colín

University of Oklahoma