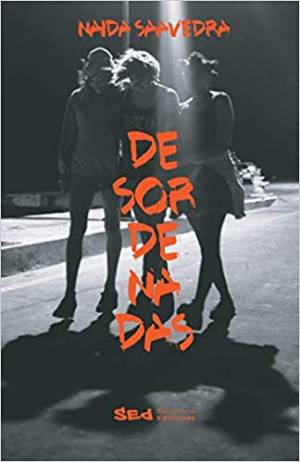

Desordenadas. Naida Saavedra. Miami: Suburbano Ediciones. 2019. 124 pages.

“Every few weeks she would shut herself up in her room, put on her scribbling suit, and ‘fall into a vortex’, as she expressed it, writing away at her novel with all her heart and soul, for till that was finished she could find no peace.” This passage from Louisa May Alcott’s timeless classic Little Women could well have been one of the mantras of the Venezuelan writer and academic Naida Saavedra while she was composing—in Massachusetts no less, a place where she lives and teaches, and the same state where Alcott wrote her celebrated novel—Desordenadas, a collection of stories about women who, though separated by time, share the same space.

“Every few weeks she would shut herself up in her room, put on her scribbling suit, and ‘fall into a vortex’, as she expressed it, writing away at her novel with all her heart and soul, for till that was finished she could find no peace.” This passage from Louisa May Alcott’s timeless classic Little Women could well have been one of the mantras of the Venezuelan writer and academic Naida Saavedra while she was composing—in Massachusetts no less, a place where she lives and teaches, and the same state where Alcott wrote her celebrated novel—Desordenadas, a collection of stories about women who, though separated by time, share the same space.

The Pilgrim’s Progress by the Puritan preacher John Bunyan—an allegorical novel that constituted a kind of manual for how to comport oneself—was a text that informed the first section of Little Women. But its influence was also destabilized by the American author, who replaced the male pilgrimage with a woman’s, and moved the story to the modern age. Saavedra continues this wonderful project in presenting us with stories of women who subvert the patriarchal world by taking ownership of and reinventing their own standards of proper behavior. The pilgrimage of her characters involves confronting situations and conflicts that are both current and timeless—family life, poverty, immigration, academic aspirations, sexuality—along with its intersectionality with agency and the female body.

In an interview following the publication of Desordenadas, when asked about the most important book she had ever been gifted, Saavedra pointed to A Room of One’s Own: “I always carry that text with me; Woolf understands me just as much as I understand her.” This influence is palpable in Desordenadas, as we find a space of one’s own for each of Saavedra’s characters—a small matriarchal domain that offers an exquisite constellation of stories populated by and focused on women.

The first story, “Una cosa sin sentido” [A senseless thing], provides an early key for the otherness that vibrates throughout Saavedra’s collection. The narration unfolds like a treatise on writing that breaks the expectations and commonplaces of the creative process. The writer-narrator confesses to us that she rarely finds her own characters appealing, and instead makes fun of them: “I even forget their names or mix them up.” She also resists language norms—she would appreciate the use @ and x to replace gendered nouns—and later describes her frustration with “a language that’s so masculine,” in the same way that Jo in Little Women rejects the categorization others tried to impose upon her: “I’m not a writer from there, because I began to write here…and I’m not a writer from here because I first published stories there.” The characters this narrator creates don’t pay much attention to the rules either, to the point that she herself often can’t control them: “My characters are from wherever they want to be from and talk however they feel like talking.”

Considering that Little Women was published in installments in a newspaper, it was a delight to discover that two stories in Desordenadas evoke that same genre. “Cuatro Lauras” [Four Lauras] and “Vos no viste que no lloré por Vos” [You didn’t see that I wasn’t crying for you] develop through fragmented narrations with subtitles that bestow an episodic air to each of the stories. But this formal twist plays with the structure of serial romantic novels, disrupting the expectation of a happy ending, opting instead for resolutions in which women must face the consequences of bucking convention without the redemptive intervention of a male character. They, and they alone, are the heroes of their stories.

“Vos no viste que no lloré por Vos” subverts chronological narration, adhering more to the fractured and chaotic structure of traumatic memories. The borders between reality, illusion, life, and death blur: “Mama, mama, why won’t you all answer me? I hear you sob but I can’t see you…Where am I?…Can it be that it’s still yesterday?” In the narrative universe of “Cuatro Lauras,” there is no space for weddings, nor for redemption. There are hardly any men either. It is as if the four Lauras have reached an agreement that the only way to reclaim their own space and distance themselves from patriarchal discourse requires banishing any trace of a masculine presence in their lives.

It is precisely this ending that many female readers would have wanted for Jo March. It is the ending that Alcott herself—who decided never to marry—desired for her semi-autobiographical protagonist. Alcott had to give in to the pressure of her editors—even allowing for the unexpected twist in which Jo turns down Laurie’s proposal—and write for her heroine the only ending acceptable for a woman in that moment. For this reason, it’s an immense satisfaction to encounter endings in Saavedra’s collection where no man appears to rescue the female characters. Where the women, no matter the situation, proclaim themselves owners of their mistakes and their destinies. Owners of their voices and their stories. In the introductory note, Saavedra shares her intention to “stitch together pieces of lives so that they can have a body and a space to which they can belong.” In this way, just like Meg, Jo, Amy, and Beth, the women protagonists in Saavedra’s stories personify different aspects of the female experience. From the most quotidian episodes to the most horrific, like the one described by the protagonist of “No llores mi reina” [Don’t cry, my queen]: “I felt like a knife was entering me and piercing me again and again and breaking me and breaking me and breaking me.”

On the back cover of Desordenadas we read that “just as Simone de Beauvoir inspired new ideas for women in the 20th century, the characters in this book, ferociously contemporary, immerse themselves in the conviction that they can only redeem themselves through chaos.” I imagine the French feminist as a girl, playing Little Women with her sister. This is the story told in the The New Yorker by columnist Joan Acocella, who adds that Beauvoir always chose to represent a writer character in her work because she liked to see herself as Jo—with the hope that she also would find her place. It comforts me to think that in this way, just as Alcott’s uncontrollable March sisters inspired Simone de Beauvoir, and the unruly oeuvre of Virginia Woolf inspired Naida Saavedra, so too will the wildness of women writers—both then and now—continue to inspire new generations of women to transgress and push boundaries, to tell their stories and to reclaim a space of their own in whatever spheres they would like to belong to.

Melanie Márquez Adams

University of Iowa

Translated by Travis Price

Melanie Márquez Adams is the author of Mariposas Negras, a short story collection. A 2018-19 Iowa Arts Fellow, and recipient of an International Latino Book Award, she is currently an MFA candidate in Spanish Creative Writing at the University of Iowa. Her bilingual collection of personal essays is forthcoming from Katakana Editores.

Travis Price received his MFA in creative writing from North Carolina State University. He is currently translating short stories by Uruguayan writer Marcelo Damonte, while working on a novel set in Uruguay. He lives in Philadelphia.