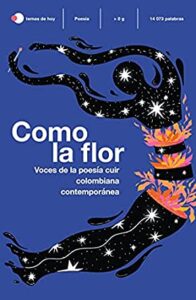

Bogotá: Editorial Planeta Colombia. 2021. 121 pages.

Con mi boca en tu sexo/ o tu sexo en mi boca

se vuelve, al fin, inteligible/ el idioma en que se cifran

los organismos vivos

[With my mouth on your sex/ or your sex in my mouth

it becomes, at last, comprehensible/ this language encoding

living organisms]

Juan Diego Otero

la flor, decía alguien,/ es el cerebro de las plantas

pero hay que decir/ es un cerebro que se expande

en el plano del sexo […]

como la flor del borrachero,/ como la del brócoli,

ejemplifican una tarea/ impensable en otros reinos:

moverte sin ir

hacia lo que deseas

[the flower, someone said,/ is the mind of the plant

but it needs saying/ it is a mind that expands

along the plane of sex […]

like the Brugmansia flower, like the broccoli flower,

they exemplify a task/ unthinkable in other kingdoms:

moving without going

toward what you desire]

Eliana Hernández

There are books that are like the greater jungle, like the heart of Pachamama, that are an open-air house. And because they are so big, because they are open with no roof overhead, all of us fit in these houses, all the oddities, the socially marginalized, and also the poetically excluded. But for there to be an outside, there has to be an inside, and the houses that we are taught to live in almost everywhere on Earth—this common home, the third planet from the sun—are houses in which to be and think correctly, in which the normative (hetero, cisgender, white, and belonging to the privileged class) slinks like cultural DNA and becomes the blue pill that designates us as worthy citizens. That is, this “good and beautiful,” the Greek kalokagathia, only happens in small houses where social conscience or love have only barely found their way in through some crevice.

There are books that are like the greater jungle, like the heart of Pachamama, that are an open-air house. And because they are so big, because they are open with no roof overhead, all of us fit in these houses, all the oddities, the socially marginalized, and also the poetically excluded. But for there to be an outside, there has to be an inside, and the houses that we are taught to live in almost everywhere on Earth—this common home, the third planet from the sun—are houses in which to be and think correctly, in which the normative (hetero, cisgender, white, and belonging to the privileged class) slinks like cultural DNA and becomes the blue pill that designates us as worthy citizens. That is, this “good and beautiful,” the Greek kalokagathia, only happens in small houses where social conscience or love have only barely found their way in through some crevice.

And so literature, like the back of a dragon or a mare, like the manta ray’s sanctuary, like weeds or undergrowth, is here, exists, reappears, is reinvented, becomes architectural material with which to “desfigurar los hábitos lingüísticos” [disfigure linguistic habits] (Vélez 37), and also to lay the foundation of pillars in the hopes that one day they too may disappear and we will start over, and with this other opportunity, in a world vaster than a simple Eden, no one will be left out, no one will suffer from a desire that “navega sin rumbo” [sails aimlessly] (Salgado 35). That is what I think, that this house, for which “big” is now too small a word, was created on the eighth day, when the god that doesn’t exist died and poets sprouted from seed.

Yes, Como la flor is one of those house-books, a queer/cuir/weird anthology where I myself as a poet found my own plot of land. It is the first anthology of contemporary queer poetry edited in Colombia, and, more than just a book, it is evidence of a community: a hive, a shoal, a school, herd, flock, pride of poets. That is what this book ended up being: a habitat, but also fauna and flora.

The editor, Salomé Cohen, and the compiler, Alejandra Algorta, have brought together thirty writers from different literary backgrounds; authors who, from the emptiness within (that allows you to live on its edge) created an ark that seems to be built of woes, “con la lluvia, con el llanto, con el agua de un río dulce” [with the rain, with weeping, with a sweet river’s water] (Alonso 56), with “carne destajada/ valle de lágrimas” [shredded flesh/ valley of tears] (Barbosa 63), with “explosión por el pecho y saliva en la cabeza” [explosion in my chest and saliva in my head] (Ardila 73). But this ship, which seems to float in the history of the marginalized, also contains rooms with latex on gums (Lemus 69), cherry kisses (Castillo 93), pineapple, water lily, and café tinto (Sanín 80), mosses, lichens, and angel hair (Enciso 84).

This ship, house, paradise lost, carries words: lustful, sentimental, anxious, ironic, rebellious words; but more than words there are feelings that escape adjectives and are only known to those of us who were there. And so this book returns the affront to established society, because all the poems are a sentencing, almost a premonition: the proliferation of the tortas, the gays, the travas, the maricas, the bisexuals and the nonbinary. It’s a book as seed, creating pathways in the jungle and in asphalt, it’s the abnormal reproduction of fruits, animals, and flowers, it is a bestiary of passions that reminds everyone, you as well as us, that we share the same speck of dust, and that when we deviate and hold fast, when we choose to be as we are, we do so against the rule that today is the exception, and we work together to dissolve it.

What more is there to say? Perhaps this review, like the poetry anthology itself, is a way of publicly exposing pleasure as a political form of lovemaking between freaks. In that, the queer, the weird, is found. But it is also found in thinking of poetry as an infectious microbe that forces asthmatics to use inhalers or the ill to use oxygen tanks, in poetry as a “sustancia escasa y viscosa” [scarce and viscous substance] (Angueyra 60), as “una silueta que se confunde” [a muddled silhouette] (Múnera 38), as the only voice that will still be murmuring into our ear “después de ser todos/ los animales […] todos los animales enterrados […] y aunque extrañamos/ los esqueletos/ nos quisimos para siempre” [after being all/ the animals […] all the buried animals […] and even though we missed/ our skeletons/ we loved each other forever] (Ganitsky 47). Queerness as creativity and endurance; also as affection that comes into existence at the edge of an abyss, always.

What I mean to say, after so much contemplation that muddles this review with a manifesto of pleasure and righteous anger, is that queerness (as sexual strangeness but also poetic strangeness) does not have an essence but rather a history. The history of those of us compelled by an uncontrollable drive to invent a life with body and with word; the history of a few beings who insisted we create radical ways of life which, rather than separating (the human from the animal, the hetero from the gay, the body from the word) would be a source of creativity and freedom, where every type of existence in and of itself would be worthy of being experienced. So yes, Como la flor is also a siblinghood of nonconformists—in our sexuality, our gender, and our literature—where bonds beyond blood are formed, a meeting within a family made up of strangers unified by solidarity. It is a book and a ship and a garden that is both pasture and jungle, it is a house where “no le dejaré poner cosas en mis paredes/ por más papeles que sean/ por más bautismos o sentidos/ que nos quieran dar” [I will not let them put things on my walls/ no matter how many papers/ no matter how many baptisms or meanings/ they want to give us] (Tengono 97).

From this nonconformity that brought us together emerged pistils, leaves, hybrid caricatures, monsters, like the rebellion of a live youngling that is not human, but also—from what some would call the depths of aberration—the construction of this book, as a new way of poetry and of dignity.

And, because naming ourselves is another form of existing, a rite of initiation, an explosive testimony, here we are: Alejandra Lerma, Alejandro Múnera, Amalia Andrade, Ana López H., Andrea Juliana Enciso, Andrea Salgado, Andrés Ardila, Carolina Dávila, Cris Tengono, Eliana Hernández, Estefanía Angueyra, Fátima Vélez Giraldo, Francisco Bárcenas Feria, Ivonne Alonso-Mondragón, Johanna Barraza Tafur, Juan de Dios Sánchez Jurado, Juan Diego Otero, Kirvin Larios, María Luisa Sanín Peña, Paula Alejandra Castillo, Pedro Adrián Zuluaga, Pedro Carlos Lemus, Pedro N. Villegas, Rodrigo Marel, Sebastián Barbosa Montenegro, Solara Sosa, Tania Ganitsky, Tina Pit, Violeta Gómez, and Yenny León.