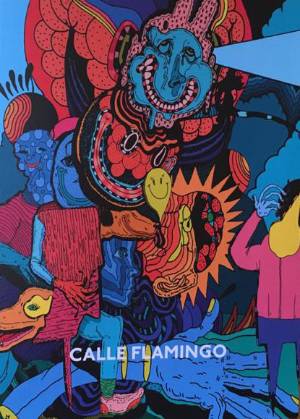

Calle Flamingo: Antología Marica. Izka Lozano Rodriguez (ed.). Bogotá: Editorial Nomos. 2020.

Nobody cares about the body of a fag in a wig

LoMaasBello

Calle Flamingo

This is street writing; real street writing. A book from the barrio Santa Fé, Bogotá, Colombia. A book of prostitutes, transvestites, lesbians, of bisexual, queer, nonbinary people, of people living on the streets. A book of voices that have been silenced and the lives lost along with them. Lives revived, reborn, remade through literature, a superpower once said to belong only to the geniuses, the enlightened, those touched by the muse.

This is street writing; real street writing. A book from the barrio Santa Fé, Bogotá, Colombia. A book of prostitutes, transvestites, lesbians, of bisexual, queer, nonbinary people, of people living on the streets. A book of voices that have been silenced and the lives lost along with them. Lives revived, reborn, remade through literature, a superpower once said to belong only to the geniuses, the enlightened, those touched by the muse.

When I finally got my hands on this book—after its launch was delayed by the quarantine, after craving it so badly when I saw the promo videos of trans women taking to the streets, bookshops, cafes in all their naked splendor—I spent days reading it, bit by bit, because the power (almost magic) within it was more than anything my thirty years and counting as a reader, my decades thinking I knew what literature was, could ever have prepared me for. I could smell it. I can still smell it as I write this, trying to inhale through my nose something our ‘civilized Western society’ is yet to absorb, through either head or heart. I touch it, I touch the middle pages, written in braille, on beautiful queer pink paper, that says “if you have to hold your ground, better to do it sitting down and looking respectable (…) That’s it, let those sons of bitches come, but we’re not going anywhere”. I want to use my senses to understand where these words—all these voices, stories, poems—come from. As I read them today I learn that the only worthwhile poetic act is to live for revolution and to live to party, at one and the same time; that “ripping apart and being reborn are the same thing”, as Luis X says in the poem “Trans-mutación”.

I read it, I reread it and I try to put a verb to it. I do this whenever something changes my life – I try to define it through an action. For this book I choose the verb romper, rupture, break, from the Latin rumpĕre, which means to break a whole violently into pieces, to undo its totality, because the trans, LGBTI, queer struggle has been fought by breaking things apart, tearing them up: streets, walls (try asking the memories and scars of Greenwich Village), proper literature, polite speech, the dictates of the Real Academia Española; breaking open minds, institutions, the established order, as Brian Velasco says in the book’s preface. Breaking open, like light breaks open darkness, revealing what’s been kept hidden within its depths. This is a book that shows what others will not tell: that many people have had to break life apart to remake it, trying not to be killed in the process.

Calle Flamingo. Antología Marica is a book about all possible freedoms, but above all one: the freedom to be and not to have to die for it. It is a book that shows life from the fringes, sharpening words when they’re no longer useful.

It all began in 2019, with queer and non-binary poetry and writing workshops organized by Libros del armario, an organization that promotes the reading of texts on gender and sexuality, and part of the Red latinoamericana de literatura diversa [Latin American Network of Diverse Literature]. They launched the project together with the Red Comunitaria Trans de Bogotá [Bogotá Trans Community Network], inviting the writers Giuseppe Caputo and Henry Gómez to work with participants who, in many cases, had never written anything before. This book came out of those workshops, the testimony of a literary and counter-cultural family, of people unafraid to expose the pain in the truth of their lives – because no act leaves us more exposed than the act of writing. It is a book like a body that comes at you from both sides in a fight, like a record, the A-side a poetry blade, the B-side a prose knockout.

When I first heard about Calle Flamingo, the title made me think of that John Waters film from the seventies about Divine, a drag queen who lives in a motor home and gets into a feud with a gay couple that make a living stealing babies to sell to lesbian couples. It was the film’s name, Pink Flamingos, that brought it to mind, but while Calle Flamingos ranks nowhere near it on the absurdity scale, when I finally read the book I realized the parallel went beyond their titles alone. It was something about pushing limits, transgression. They both discomfort, unsettle. Calle Flamingo is that awkward word, the voice of the people we don’t hear, people who have to break open their own safe space. It is Lala Switch confessing “I was born blood (…) without gender, without God”, or Katalina Ángel “savoring the sound of the padlock as it opens”; it is the voice of Iska Lozano accepting her survival because “the sea didn’t wash away the sickness or clean the wounds”.

I like anything that shows life as a political act, and for me, nothing does this better than literature. Calle Flamingo is a declaration, a voice to the four winds, proclaiming what a culture has kept quiet. It is like a giant wave rising over a city with its back to the sea. It is a book that names, that shouts here we are, we exist, we write. The weirdos, the different, the diverse, the queer, the transvestites, the prostitutes, cursing language in its own words. The people brave enough to name themselves, using their voices to invoke the bodies, cuerpas, that are no longer with us.

Literature breaks apart, what breaks apart is changed, what is changed speaks of the flowers of springs past, but also, and above all, of the flocks, schools, herds of a thousand species that are here, that have always been here, and that are now acknowledged, named, made permanent, even with their knees grazed by the sidewalk, as Lorena Daza says in “Amigas las cicatrices” [Friendly scars]. Like when “a new story is created from the rubble”, this is one story made of many, those of Camila Murillo, of Nico Merchán, Luna Laverde, Ángel López, Ammarantha Wass.

How much the world needs books like this; bombshell stories whose words draw a family portrait, a body of many eyes and many arms, three tits, orifices, multiple members. It lays dynamite on the last of the ivory towers, transforming them into a rite of passage for a stuttering society. Calle Flamingo is an anthology, but it is also a queer mythology, an origin story that takes us to the beautiful, messy edge of things, where life imposes itself, immense, without asking permission, and takes, grabs, possesses, handles, disarms, reinvents the word, to speak—in broad daylight and pre-watershed—of our mixed bodies and our crossed identities. Because yes, there are duties in literature, though some say otherwise, and one is to point out the immense rifts between us, and to see if we can begin to close them.

Ivonne Alonso-Mondragón

Translated by Robin Munby

Ivonne Alonso-Mondragón is a scholar of philology and literature at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Her research centers on subjects related to feminism and literature, as well as the literary tradition dealing with the armed conflict in Colombia. She teaches writing at the Universidad de los Andes and in the Creative Writing programs of the Universidad Central in Bogotá, Colombia.

Robin Munby is a freelance translator from Liverpool, UK, based in Madrid. After graduating in modern languages from the University of Sheffield, he worked in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, before returning to the UK to complete his master’s in translation studies at the University of Glasgow. His translations have appeared in the Glasgow Review of Books, Wasafiri Magazine, and Asymptote Journal. His interests include Cuban literature and Russophone literature from Central Asia.