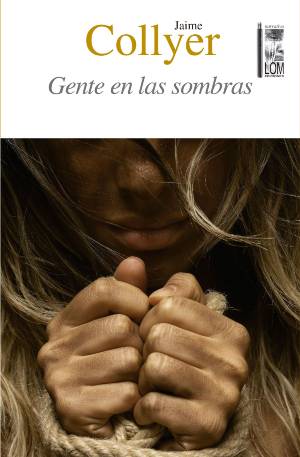

Gente en las sombras. Jaime Collyer. Santiago de Chile: Lom Ediciones. 2020. 202 pages.

Jaime Collyer, with his distinguished career as a storyteller, was part of the generation of writers active during “the transition”—witnesses to and voices of a very particular period in Chilean history. In his work, political themes often weave in with allusions to metaliterature. His most recent novel, Gente en las sombras, offers a new take on the settling of scores that occurred when dictatorship gave way to democracy.

Jaime Collyer, with his distinguished career as a storyteller, was part of the generation of writers active during “the transition”—witnesses to and voices of a very particular period in Chilean history. In his work, political themes often weave in with allusions to metaliterature. His most recent novel, Gente en las sombras, offers a new take on the settling of scores that occurred when dictatorship gave way to democracy.

His protagonist, Álvaro Larrondo, a historian with dreams of writing fiction, is put in charge of a project to interview survivors of a detention facility known as Camp D that was active during the dictatorship, along with the retired colonel, Efraín Prada, who ran the camp. A young architect, Svetlana Braun, is chosen to redesign the camp and convert it into a public memorial, whose opening will coincide with the publication of Larrondo’s report: “A book of some one-hundred, one-hundred twenty pages, with photographs…It will be a photographic memorial, which we will distribute later via the official channels,” Larrondo is instructed by Beregovic, a government functionary in charge of the project in which Svetlana will manage the visual design. “You do have experience in those things, I guess…Institutional records, archival reports….You are after all a historian.”

The assignment requires Larrondo to get to know Colonel Prada. The two develop an ambiguous relationship in which Prada is tempted by the possibility of an autobiographical retelling of his experiences at the torture center. The story is set in 2005 near the end of the Ricardo Lagos administration. Through the perspective of Larrondo, Collyer poses his own questions as a writer, wondering about his generation, about the relationship between language and politics, about secrets, memory, and forgetting. It is fitting that the novel opens with an assassination attempt on Efraín Prada, and then flashes back to follow the remodeling and inauguration of the memorial, Camp D. Efraín Prada proves to be a charming and complex figure, who reads the stories written by Larrondo and possesses his own pseudo-literary ambitions: “With his stories it is the same—they don’t make you think too much,” Larrondo says of Prada’s writing. “All of a sudden the matter is flipped on his head, as when one jumps into a void and the only thing left to do is free fall until the ending arrives….I liked your strategy….Congratulations, my friend.” In this way Prada goes on weaving his fabric around Larrondo. These comments about the colonel’s writing also describe, in a game of mirrors, Collyer’s own novel

Larrondo also interviews three survivors who he chooses from the dossier he is given to enrich his report, but the figure of Prada imposes with his dangerous and threatening nature. Larrondo argues with Svetlana after being pressured by Beregovic, who tells him, “We would like your report, the one you are preparing for us, to be something serious. Well-balanced! A story without high emotion, something spare, that adheres, nonetheless, to the truth. A book that leads toward reconciliation—toward the country that we all desire.”

How can one write such a report in the presence of figures like Prada, or the mysterious Godofredo Ruy Díaz, who has known, and manages and represents the dictatorship’s ‘civil side’? What does reconciliation really mean to all these characters?

This seems to be the great difficulty for Larrondo each time he interviews the survivors, and especially when he meets with the once powerful Efraín Prada, who knows perhaps too much, which could cost him dearly.

Questions about the relationship between memory and peace, between scar and open wound, between forgetting and adapting, between resignation and hope, are the primary concerns of Collyer and his alter ego Álvaro Larrondo.

Master of his domain, Collyer, wise storyteller, lays down twists and turns to create suspense and transform the novel into a dark thriller with an uncomfortable ending that underscores the talents of the author.

The Chile that lived through the dictatorship does not come off well. Ruy Díaz declares, “A free country? Don’t make me laugh! This country has never been free, Beregovic, nor has it deserved to be. An embittered country, that’s what it is. An ungrateful country, incapable of appreciating the enormous work that we did. Neither you nor your friends in the party would be where you are were it not for the labor we took on and that now they want to tarnish….We would all be in the gulag, my friend, behind a wire fence, in some hard labor camp, you and me both. Watched over by the same scum that Prada locked up during his nighttime raids. It seems you don’t understand what we freed you from….”

The tension generated by the novel’s ambiguity, by the duplicity of characters closest to power, creates a narrative readers can’t put down until they know how the relationship between Larrondo and Prada will end, and understand the very first scene that we read: the assassination attempt.

Divided in four parts, the novel is appealing because it interrogates the most brutal doubts that surface during the transition from dictatorship to democracy: Can memory be more than a memorial? Or is the memorial of Camp D a sophisticated form of forgetting? What is the limit between memory and betrayal? How much does one have to forget to salvage freedom from the weight of history?

All these considerations are packaged in a nimble and captivating story, thanks to the skillful pen of Jaime Collyer. It’s a story in which Larrondo and Svetlana will make a painful discovery about who writes the history of a country. And why it’s important that it is written and continues to be written.

Marco Antonio de la Parra

Translated by Travis Price

Marco Antonio de la Parra is a Chilean writer and playwright, and a member of the Academia de Bellas Artes of the Instituto de Chile. He has been awarded the MAX 2003 prize for Hispano-American theatre, the Premio Municipal de Literatura, the Premio Consejo Nacional del Libro, and the 1997 Premio José Nuez Martín. He has received Guggenheim and Iberescena grants. He has published almost 100 titles, including theatre, essay, and narrative.

Travis Price’s fiction has appeared in The Collagist, pioneertown, Clockhouse, and Toho Journal. He is currently working on a novel set in Uruguay, where he lived in 2018 while completing a Fulbright. Travis lives in Philadelphia.