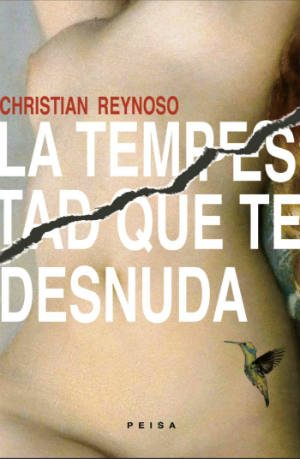

La tempestad que te desnuda. Christian Reynoso. Peisa, 2019. 178 pages.

La tempestad que te denuda [The storm that strips you], Christian Reynoso’s recent novel, has weathered many storms. I’ve witnessed the ways the author, like a great surfer, has beaten against the fierce waves of the storyline. In 2016, the author travelled to Brussels, Paris and the island of Sardinia to lose himself in the labyrinth of fables, which, occasionally, it appears he really lives, and then to find himself once again the captain of his own ship. All these maritime metaphors come from Rimbaud, since Reynoso went through periods of intellectual vagabonding under the influence of malevolent nineteenth-century artists, the century of creation par excellence.

La tempestad que te denuda [The storm that strips you], Christian Reynoso’s recent novel, has weathered many storms. I’ve witnessed the ways the author, like a great surfer, has beaten against the fierce waves of the storyline. In 2016, the author travelled to Brussels, Paris and the island of Sardinia to lose himself in the labyrinth of fables, which, occasionally, it appears he really lives, and then to find himself once again the captain of his own ship. All these maritime metaphors come from Rimbaud, since Reynoso went through periods of intellectual vagabonding under the influence of malevolent nineteenth-century artists, the century of creation par excellence.

Where does the current in La tempestad que te desnuda take us? The novel revolves around a young dancer and her romantic experiences—Silvana Oblitas—who refuses to give up her dedication to and fascination with music and dance, a passion which will “overcome” any misfortune or vicissitude.

Reynoso has created this female character, and with the reliability of an omniscient narrator, he dives into her heart of hearts to discover her worries and weaknesses, along with her strengths, as she faces a crisis. She moves through a critical period in which her professor Almudena Dreyer and her friends become an important foundation supporting her so she doesn’t collapse and abandon everything.

One of Reynoso’s great virtues as a storyteller is his talent for developing introspective characters and for describing and connecting his characters’ emotional states with their environments. As a result, a street, a shop, an object are not what they appear. Rather, they are part of the characters’ intimate reality. Reynoso’s characters evolve; they fundamentally change from one state to another, which is a basic principle of the contemporary novel: the evolution or involution of the protagonist.

Silvana Oblitas is to Reynoso what Madame Bovary was to Flaubert: the author’s daughter and alter ego. But Silvana is not middle-class, rural and married, as was Emma Bovary. Silvana here and now represents women of all social classes who suffer harassment, are victims of abuse, rape, and the worst kind of machismo. And this includes hypocritical neomachismo, the product of a backsliding society that rails against migrants escaping war, hunger, and organized crime; ethnic minorities; and women in all territories who fight minoritization and feminicide through movements like Ni una menos, mentioned in the novel.

As preparations for the musical Ciudad Paraíso [Paradise city] are underway, Silvana suffers brutal violence at the hands of the male character Mariano Santander—a musician and an old friend from school—who is also Silvana’s boyfriend. The production is described as a “conceptual musical about happiness and the search for identity” (22), however, in the characters’ lives, exactly the opposite will ensue. Silvana is a victim of Mariano’s jealousy, harassment and physical and sexual violence. Thankfully, a group of friends and her professor Almudena attempt at all costs to save Silvana from the depths of despair.

La tempestad que te desnuda is built on constant temporal and spatial ruptures. A modern-day object, such as a cellphone, juxtaposes periods of time. After attacking Silvana, when Mariano takes her cellphone, we as readers no longer need the typical justifications of an omniscient narrator of the past, since Mariano, after having physically and psychologically abused her, looks through her phone and imagines the life Silvana has led. As a result, she tries to run away from herself, as she feels lost, her identity gone. During this escape, she has another intense experience with a young man at a resort, which becomes the basis for not accepting her own submission or feeling like she has betrayed herself.

But Silvana and Mariano have a secret that is revealed just before the novel reaches its denouement: a little something the narrator hides in his sleeve that further nuances each character’s personal drama. Some might say the secret explains the characters’ behavior as products of their environment and lived experiences. In any case, it is a prevailing theme and it fosters a moral or ethical argument. And in lieu of explaining or justifying their behavior, the author displays the elements disarticulating our discriminatory and consumerist society.

As for Silvana, the family secret is the enigma of the absent father who was disappeared during the internal conflict between Shining Path and the Peruvian government. For some psychologists, the theme of the absent father leads certain young women to identify a father figure in their partners—a father figure who provides for them and on whom they can depend. A core issue central to the protagonist’s identity is the search for her father. During the war, loyalists to Shining Path died along with individuals who had no political ideology whatsoever. One of them could have been Silvana’s father. In the big Ni una menos march narrated in the novel, Silvana tells her friend Yuyu her mother’s long-awaited revelation regarding what happened to her father.

This entire narrative frame is contextualized at the beginning of La tempestad que te desnuda, where the topic of abortion is outlined. The novel begins with Silvana in a medical clinic bed waiting for the moment she will undergo an abortion to terminate an unwanted pregnancy. In this way, the reflection on the abortion theme is presented with its most controversial aspects at the fore. It’s developed at the end of the novel with the dance teacher, Almudena, when she meets with her ex-partner, Giraldo, and they get into a debate about Silvana’s abortion and its impact on her body and psyche. Reynoso suggests the dilemma, whose root is more philosophical than physical. The situations surrounding the practice of terminating a pregnancy are many and all are justified in each individual case. In a recent interview, Reynoso states that he doesn’t know if his story should convey something concrete in the end. Instead, he leaves the likely answer to the reader. The answers are many, as many as individual experiences and factors—internal and external, cultural, socioeconomic, etc.—revolving around an unwanted or unplanned pregnancy. The solution, Reynoso says, is beyond him as an author. The important thing, he adds, is having told a story that invites us as a society to consider the question.

The denouement leaves us with the figure of Mariano, who also hides a secret related to domestic violence: these are experiences he had in his youth that have remained buried, almost forgotten, in his subconscious, but which emerge later, when he flees his own violence, his narcissistic perversity and which lead him to think of himself as a wretched man. “I understood that I didn’t have anybody to talk to. That I was alone, totally alone, in the world, like a fugitive, placeless, lost in the distance, like I’d truly been born under a bad sign” (170), Reynoso writes at the end. With this ending, we see Mariano wrapped up in his own misery and solitude while the confrontation of forces in the narrative are resolved. Meanwhile, male and female readers place their bets, win or lose, on these characters’ lives, depending on whose side they’re on.

Carmen Ollé

Lima, Peru

Translated by Amy Olen

Amy Olen is an Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She finished her Ph.D. in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at The University of Texas at Austin on Guatemalan Maya-Kaqchikel author Luis de Lión. Amy holds Master’s Degrees in Translation Studies (2006) and Spanish and Portuguese (2010) both from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her research interests include Central American and Andean Indigenous writing, and Translation Studies.