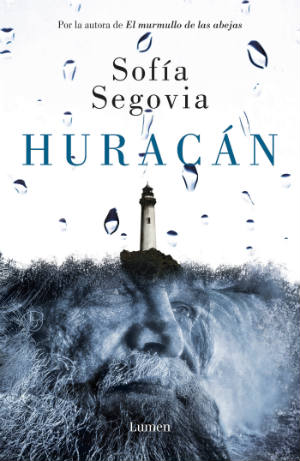

Huracán. Sofía Segovia. Mexico: Lumen, 2016.

Huracán [Hurricane] (2016) is the reinterpretation or remake of Segovia’s first novel, Noche de Huracán [Hurricane night] (2010), edited first by Conarte and later picked up by Editorial Lumen and published in 2016 as Huracán. This is her second book after El murmullo de las abejas [The murmur of the bees] (2015), one of the best Mexican novels in recent years. It recalls major Latin American literature masterpieces such as One Hundred Years of Solitude, The House of the Spirits, Balún Canán, and Pedro Páramo. In the long tradition of Carpentier’s “lo real maravilloso”, defined by the Cuban writer in his preface to The Kingdom of This World (1949) as “a miracle” or “faith,” El murmullo de las abejas presents a real and magical character, Simonopio, and his bees, which communicate with him through blood nooks and tell him the future. The Morales-Cortés family, living in a town called Linares in the state of Nuevo León, Mexico, travels back and forth to Monterrey, the state’s capital, to narrate episodes from the Mexican Revolution and the Agrarian Reform through the eyes of a landowner, Francisco Morales Sr., who learns how to dodge the law to safeguard the land where he plants his fruit trees. The story also describes the impact of Spanish flu in Linares in the precarious period of Mexican history at the beginning of the 20th Century. Segovia whispers in our ears (as the voice of one of the novel’s narrators, the narrator-character, the elderly Francisco Jr.) in an intimate conversation with a taxi driver driving him back to Linares from Monterrey on a journey to the source, now as an old man, to regain the murmuring of the bees of his adopted brother, Simonopio, and make his long life meaningful until he meets his death.

Similar to Simonopio, Aniceto Mora, el Regalado (the Given), as he was given away by his family, stars in Sofía Segovia’s Huracán. This character knows the hardship his family endures in Cozumel, an island in the Mexican Caribbean, which forces him to be exiled to the mainland. His fate is marked by misfortune and the reader walks along with him through the story of his return to Cozumel in a reunion with his past told by an omniscient, third-person narrator. The catastrophe brought about by the hurricane creates a two-fold image: the character’s hurricane-like life and his story, and the wake of two real-life hurricanes in Cozumel and their consequences for the island’s economy, tourism, and citizens. Segovia addresses human pain and betrayal in her novel, as well as the bitterness and resentment of an individual born into a social class that did not provide him with the opportunities to unfold his full potential. The real yet magical element is realized in the novel by the deceased Pinche Güero following Aniceto during his lifetime, like Prudencio Aguilar did to José Arcadio, the patriarch of the Buendía family, in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Structured in six chapters covering the life story of Aniceto Mora, el Regalado, and his family into their old age, Huracán portrays a deeply Mexican and realistic world in the tradition of novels of the Mexican Revolution, such as The Underdogs by Mariano Azuela, Las manos de mamá [Mama’s hands] by Nellie Campobello, and Al filo del agua [On the edge of the water] by Agustín Yáñez. However, Sofía Segovia solves the conflict between men, the force of nature, and politics with a language and style different from those inherited from this tradition. Her female characters, like La Gorda Nayuc, Aniceto’s wife, or his daughter, whom he raped in a lighthouse during another hurricane, redefine the position of women in a patriarchal society. Both women develop defense mechanisms to go beyond gender tyrannies: one of them injures her rapist father before leaving and the other dies, leaving him alone. Aniceto’s son, Manuel Mora, rejects his father’s destiny and grows up to be an honest, working man, the antithesis of his machista lineage. As the manager of a hotel in Cozumel during the hurricane, he proves his efficiency by handling “regios” (Monterrey citizens, or regiomontanos, vacationing in Cozumel) and “gringos” (American tourists representing the arrogance of the average American vacationing on the island). Segovia portrays and illustrates these characters (Marcela and Roberto/Lorna and Paul Doogan) to express a fine contrast with Manuel’s calmness and dignity when faced with tourists’ requests before, during, and after the hurricane. In this context, the storm becomes a catalytic agent for the novel’s action.

The title of the book, Huracán, is a double-edged sword that the author uses to create a cutting criticism of Mexican society and the hotel and tourism industry, one of the most thriving in Latin America. Furthermore, the hurricane represents a trope of characters’ hurricane-like lives in the family history of Aniceto and Manuel, father and son. As in the scene in which we see the misfortune of powerlessly waiting for the hurricane to strike: “Experience had taught him that the best thing he could do in a hurricane was run away from the storm, escape, leave, go far away. That was the only way to be safe. Manuel knew that, but he did not listen. He could not listen” (185). His duties as hotel manager prevent him from helping his wife and daughter, living in a half-built house.

In El murmullo de las abejas and, particularly, in Huracán, Sofía Segovia becomes established as one of the best Mexican prose writers of 21st Century. Her training as a communicator and writer of political speeches, comedy and musical comedy scripts, and scripts for local amateur theater has provided her with an acute power of observation of our Latin American reality. We must also read her new novel, Peregrinos (published by Penguin Random House), which tells the story of two Prussian families escaping from the Second World War, in order to track her narrative proposal. We must not lose track of this writer, who will surely make the headlines.

Daniel Torres

Ohio University

Translated by Irina Lifszyc