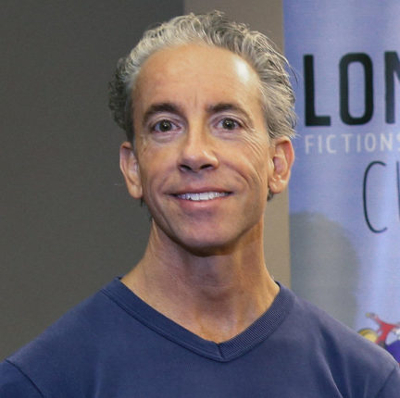

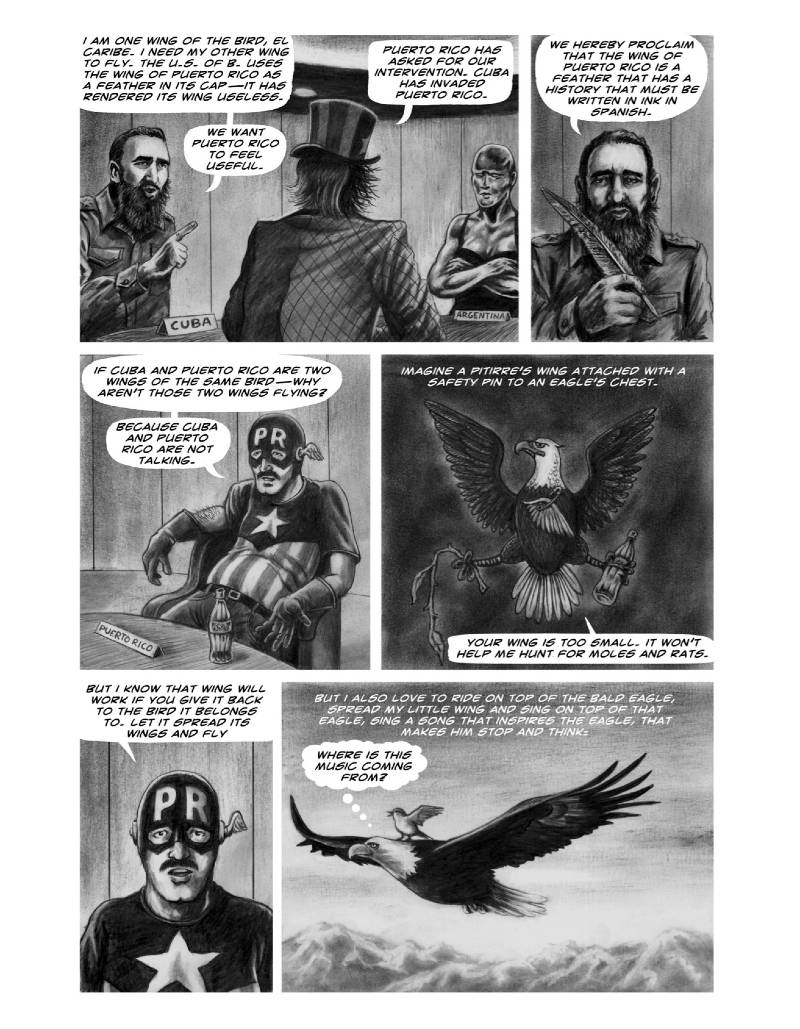

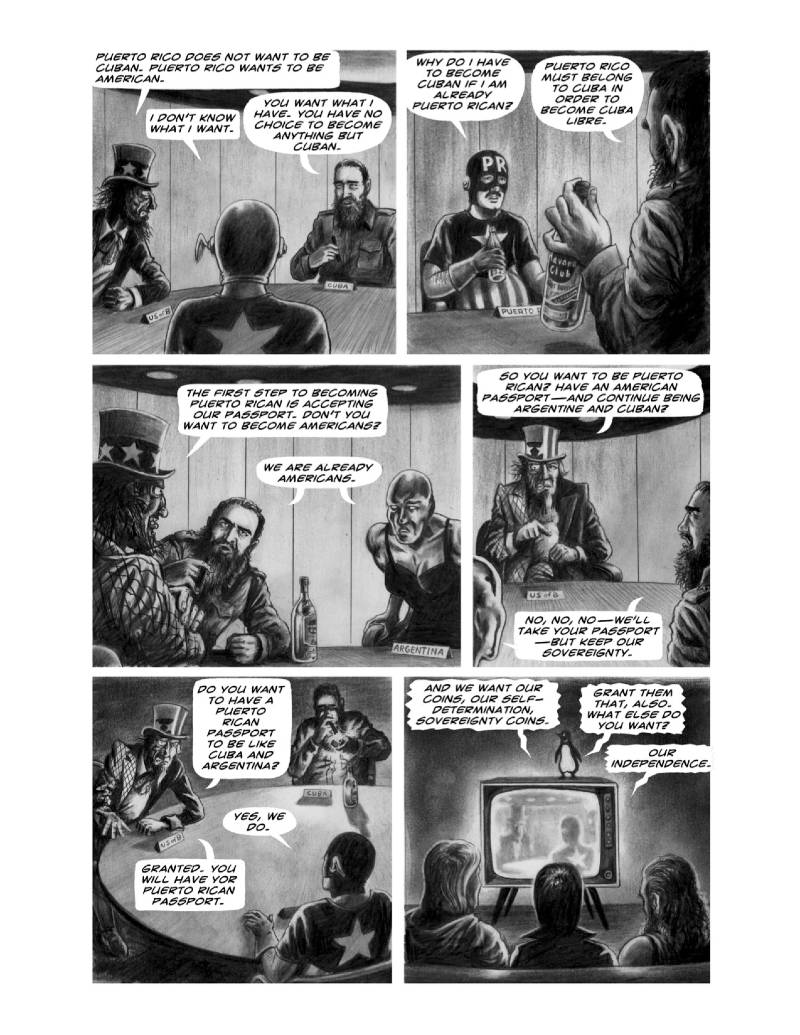

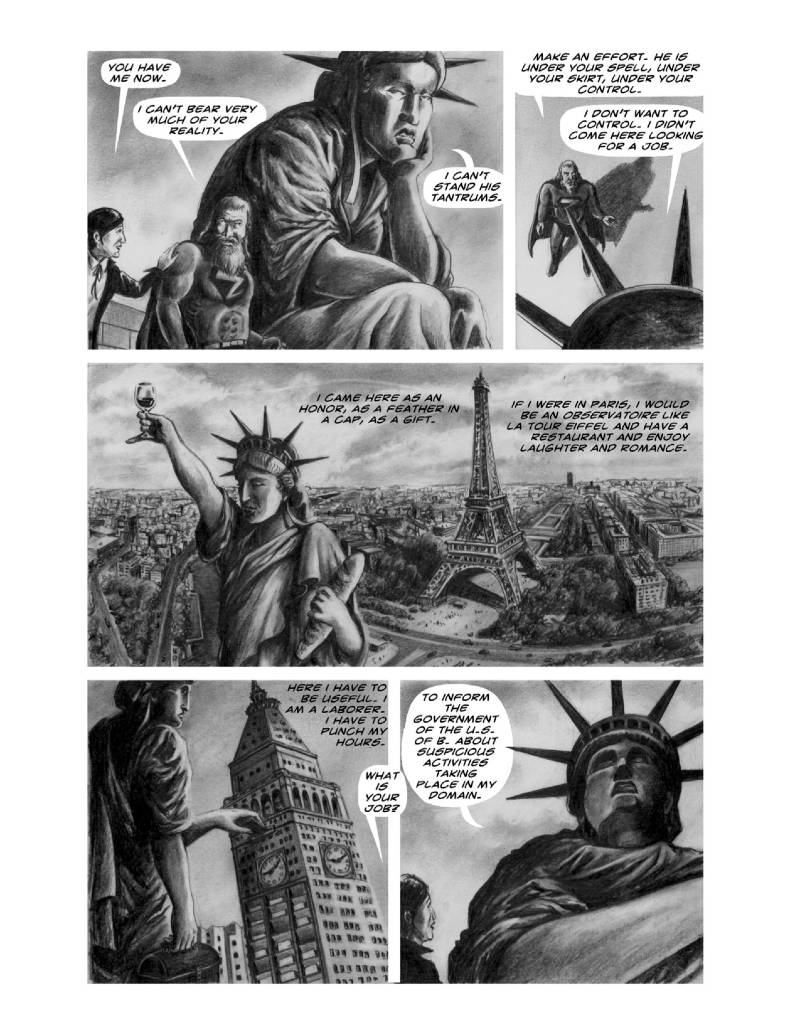

Editor’s Note: The images that accompany this interview are from the forthcoming title United States of Banana: A Graphic Novel by Giannina Braschi and Joakim Lindengren, with an introduction by Amanda M. Smith and Amy Sheeran. The full graphic novel will be published by The Ohio State University Press in March 2021. LALT is honored to publish these panels for the first time in the United States and in English.

***

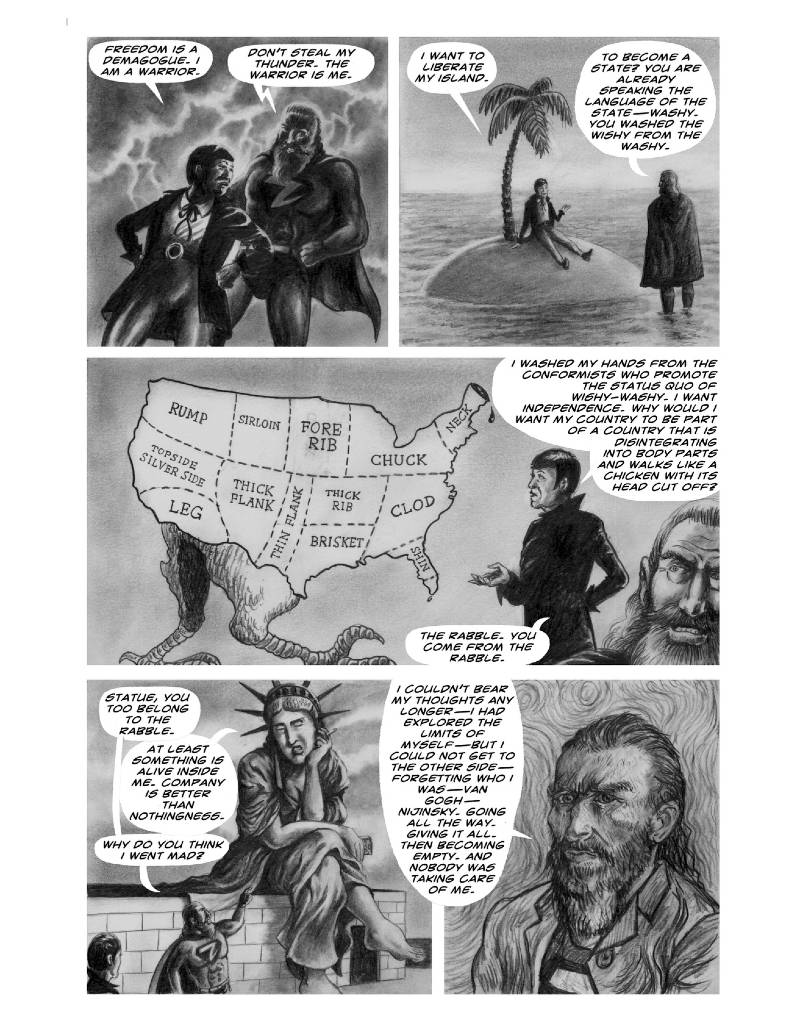

Frederick Luis Aldama and Tess O’Dwyer co-edited Poets, Philosophers, Lovers: On the Writings of Giannina Braschi (University of Pittsburgh, October 27, 2020), a collection of essays by fifteen scholars across diverse fields, exploring the forty-year career of one the most cutting-edge authors in Latin America today. In the following dialogue, Aldama and O’Dwyer discuss the ways that Braschi discovers and creates new spaces for free thought.

Braschi has been called “one of the most revolutionary voices in Latin America today” by PEN America. The Library of Congress describes Braschi as “cutting-edge, influential and even revolutionary,” noting that there are “elements of art, culture, philosophy, and politics in all of her literary works, which include the Postmodern poetry classic Empire of Dreams and Yo-Yo Boing!, credited with being the first novel to be written in Spanglish. Her latest, United States of Banana, has been described as experimental, revolutionary and profoundly philosophical. It is to be read as The Wasteland of the 21st century.” She has won awards and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, PEN America, Rutgers University, Ford Foundation, the Danforth, Rutgers, and Puerto Rican Institute for Culture. Born in Puerto Rico, she lives in New York.

***

Tess O’Dwyer: What poets, philosophers, or lovers leap to mind at the mention of Giannina Braschi?

Frederick Luis Aldama: That’s easy. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz who considered herself a free, rational, scientific spirit and a poet.

T.O.: Is there a specific trigger to that connection?

F.L.A.: Sor Juana’s poem, “First Dream.” It’s an extraordinary achievement. She based it on the scientific findings of the Renaissance, all while translanguaging a Catholic vocabulary, and an Aristotelian worldview and conceptual organization, to disguise from Church authorities her penchant for science and rational thinking, to create a prodigious verbal universe and to express the most wonderfully affective, logical thoughts. Second to mind comes Louise Glück, recently recognized with a Nobel Prize. Her poems speak to isolation, alienation, and other discords pervading quotidian, ordinary life. Braschi and Glück address our current state in its multifarious manifestations, both positive and negative, creative and destructive, hopeful and despairing. And, their poetics are driven to incandescence by heart and mind, emotion and reason—and never slip into mysticism and pseudo-foundational mythmaking.

T.O.: In the introduction (to Poets, Philosophers, Lovers), you situate Giannina within a genealogy of avant-garde artists such as Audre Lorde, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, and Claudia Rankine, while noting as well her commonalities with cutting-edge contemporaries such as Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi and Zinzi Clemmons. Why does the cutting-edge appeal to you as a framework for understanding?

F.L.A.: Giannina Braschi is one of our great Latinx vanguardista poets, performers, fiction makers. However, like other deep creators—think Roberto Bolaño, Fernando A. Flores, Salvador Plascencia—the complexity of their work at once demands attentive study and scares off the weak of heart. Like a Borges or a Faulkner, Braschi pushes hard at the limits of creation. In this sense, she’s a poet and a poet’s poet through and through. Here, we spiral into etymological roots of poiesis, derived from the ancient Greek, to make. Braschi creates new forms to carry powerful content that shakes us from our habituated states—and radically so. As such, her work educates and grows future readers. Think of the Spanish future tenses here, and not the simple one we have in the English language. The future has caught up with the present.

T.O.: As to the future, I think we’re become more future-focused since the Trump era began, especially since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. The prevailing question is no longer: How are you? Rather: What do you think will happen next? It’s fascinating how forecasting has shifted over the ages from the image, word, intuition to numbers, data, equations. Today, people turn to predictive modeling and statistics to gauge the future. Whereas, ages ago, they looked to oracles whose prophecies and revelations were poetry. The Swedish poet Ann Jäderlund calls Giannina revelation-ary. Not in a strict sense of divination or prediction, but that her poetry is one of revelations, of revealing something startling, something true, and something new. And no matter how startling or stark the vision is, it comes with a comic burst of absurdism via an uncanny cast of characters, be they oracles, psychics, witches, or fortune tellers.

F.L.A.: Or be they poets, philosophers, and lovers.

T.O.: Right! Among the many mind-bending scenes in United States of Banana is when Giannina serenades Diotima on the steps of the White House, asking her to open the doors of the Republic to poets, philosophers, lovers, while tossing her a set of keys. Hence, the title of our collection. So, what is it about the figure of the philosopher that resonates with you?

F.L.A.: We are living—surviving—strange times, Tess. In France, a teenager beheaded a young history teacher who was teaching students about the importance of free speech. The teacher used cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad as an example. In the US we have Executive Cheeto in Chief incessantly spouting white supremacist, anti-science rants, unleashing torrents of irrationalism and murderous death across the land. And, we have the sudden resurgence of chatter on Nazism-stained Heidegger in hallowed academic virtual spaces, especially those prone to Medieval-fashion mysticism; not to mention, the crawling-out of rotted-wood ideologues presented as philosophers like Giorgio Agamben.

T.O.: It sounds like the philosopher is crawling backwards like a crab. But what about the poet? The Academy of American Poets proclaims poetry has made a huge comeback. NPR reports that over the past five years, the number of people in this country who are reading poetry has nearly doubled. That is according to a survey by the National Endowment for the Arts. Are you surprised to hear that poetry is up?

F.L.A.: Surprised? No, not at all. The poet builds captivating storyworlds chock full of gods, humans, and those demigod in-betweens. In epic poems such as The Iliad and The Odyssey, we see a clear separation between the secular and the divine—and demi-divine in-between. We only begin to see the fusion of the secular and the religious in culture after 380 CE, when Christianity was declared the official religion of the Roman Empire. This fusion of state and church continues to infect theories of literary creation, intermixing myth and mysticism in concepts of the poet as oracle or prophet.

T.O.: We might disagree, but I love the poet as the seer. The first poem I ever translated was from the Book of Clowns and Buffoons in Empire of Dreams. The prose poem begins with the lines: “I have been a fortune-teller. Ages ago, I told the fortune of buffoons and madmen. You remember. I had a small voice like a grain of sand and enormous hands. Madmen walked over my hands. I told them the truth. I could never lie to them. And now I’m sorry…” The soothsayer first reveals the past…

F.L.A: As an indication of a vision for the future.

T.O.: Exactly. And, in the spirit of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi, United States of Banana deals with the science of imaginary solutions as a way to clear the deck. An oracle proclaims Puerto Rican sovereignty, and it is achieved by a Declaration of Independence. But, the island does not choose between its three political options of nation, colony, or statehood. In Braschian terms, those choices are “Wishy, Wishy-Washy, or Washy.” They are as limited a menu as mashed, baked, or fried. “Any way that you serve it,” she says, “it’s all the same potato.” The poet sees the truth, goes to the heart of the matter, and clears the deck of cynicism and irrationalism in order to create something wholly new. To be free from “feardom.”

F.L.A.: Well, given the level of cynicism and irrationalism flooding across the US and beyond, that the work of Martin Heidegger has resurfaced is not surprising. His push to go beyond being (with little b) to something deeper is simply a repackaging of the negative ontotheology formulated in the work of Christian mystic Meister Eckhart during the middle ages. The philosopher becomes a cypher for irrationalism—and anti-science. Moreover, in Heidegger’s first lecture on the Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin, he famously declared: “The thinker evokes being. The poet names the holy.” He went on to ask what it means to “poetise.” For Heidegger, the act of “poetizing” is always bringing something “anew” into being that prepares the ground for the return of the god or the gods. Indeed, poetry became his close compadre in the search for an “other beginning” of thought, and existence that reveals the essence of being and thus the essence of the sacred. The poet is the new officiant of the new mystical world to be ruled by the new religiosity and the new god or gods to come. Heidegger in his later years insisted that his whole work had been determined by the goal of giving full expression to a renewed theology. Indeed, it is this kind of modern-day mysticism and ultimately irrationalism that informs Giorgio Agamben’s philosophical outlook and leads him to declare that the real threat today is not COVID-19, but the climate of panic that science has supposedly fanned up among the planet’s population. If we are to survive as a species, today more than ever we have to remember the crucial reason for the separation of church and state, mysticism and science, lies and truth.

T.O.: “Creation means discovery of a new reality that exists but that has not yet been noticed,” says Giannina in United States of Banana. There’s a profound relationship between creation and discovery, and that is why the arts and sciences should always be taught together.

F.L.A.: The character Papá Rolo in my kid’s book The Adventures of Chupacabra Charlie says it simply, “Art creates. Science discovers.”

T.O.: What interests you about the formal devices that Giannina uses to create?

F.L.A.: She seamlessly intermixes formal shaping devices from poetry, performance art, and fiction in surprising ways—and always with what Edgar Allan Poe called the “unity of effect”: where a great will is exerted to shape form and content in ways that move the reader in particularly directed emotive and imaginative ways. And while Poe was not to become a practitioner of a borderless genre where short story and poem could become indistinguishable, he theorized this possibility. His formulation greatly influenced Borges and Cortázar, who was such a huge fan of Poe that he translated all of Poe’s works. Borges and Cortázar in turn hugely influenced Faulkner. I see Braschi’s acts of poiesis as robustly extending this line of creation and creators.

T.O.: I trust she would agree with you on that. I certainly do.

F.L.A.: Octavio Paz was working to reformulate the evolution and nature of literature. He cribbed his project from Heidegger in the 1950s. He declared that poets were mythmakers and their role was to give new life to ancient myths, period. And, according to his Heideggerian formulation, because the whole edifice of literature and art is built on poetry, then all artistic creation is built on the same ultimately religious foundations and on the same spinning of myths that a new mysticism and a new mystical frame of mind should elicit.

T.O.: Where do you see Giannina on these issues? Do any passages come to mind?

F.L.A.: “Poetry must find ways of breaking distance”—from Yo-Yo Boing! reminds us that authors work hard to reconstruct the building blocks of reality to make new our perception, thought, and feeling about the world we inhabit. In so doing they also re-create themselves in and through their uniquely fashioned styles.

T.O.: The recreating of the self is a Braschian obsession, for sure.

F.L.A.: She does this with her hemispheric translanguaging. Cortázar famously did this in a passage in Hopscotch that’s entirely written in an invented nonsense language: Gliglico. However, to get to this generative creative space where authors can see all the expressive possibilities and imagine new ones, they must bring a certain distance to the subject matter they are shaping. Cortázar talks about certain events, certain aspects of reality needing a distance in time or history to become amenable to representation. He was thinking of transcendental changes and events such as the Cuban Revolution, and also of the kind of aesthetic tools needed to be shaped and perhaps newly created. In sharing her writing process, Toni Morrison talks of the importance of not being overwhelmed by sentiment and bringing a certain “cold” distance to her subject matter in order to see clearly all of her re-creative options. Braschi’s phrase from Yo-Yo Boing! reminds us that creation centrally involves the reason system as a whole—an important reflection and reminder that resonates way beyond poiesis, the act of making, and may inflect all aspects of a good life.

T.O.: That’s beautiful, Frederick.

F.L.A.: Finally, I’d like to recall the line from United States of Banana that reads: “I have nothing against the smell of rot but something against what hides the smell of rot in the United States of America.” I don’t want to dwell here on the obvious. Rather, I’d like to use her phrase as a powerful reminder of the opposite of rot, ethics, the good and the moral enveloping growth, truth, life, and love—and the lovers of our book’s title. While Braschi often drops us into discomforting (in form and content) spaces, she does so to take us to radically new and unpredictable places, to the most surprising locations where all sorts of questions are posed and offered to our scrutiny, leading us to reflect on memory, intersectional identities, gender and race oppression, aesthetics, ethics, and metaphysics from standpoints constructed in remarkably unsuspected ways. That is, Braschi ultimately takes us to that place where we at once celebrate total freedom in art and can begin to heal and love as lovers, and so much more.