Javier Cercas was chosen by the Vatican to write a book about his journey, alongside Pope Francis, to Mongolia—a country on the geographic, religious, and social periphery, with fewer than 1,400 Catholics. We spoke with the writer about this experience and his reflection on “God’s madman,” a figure both humble and radical who dreamt of a different Church and, with humor and grace, marked a revolutionary turning point in the transmission of the Gospel.

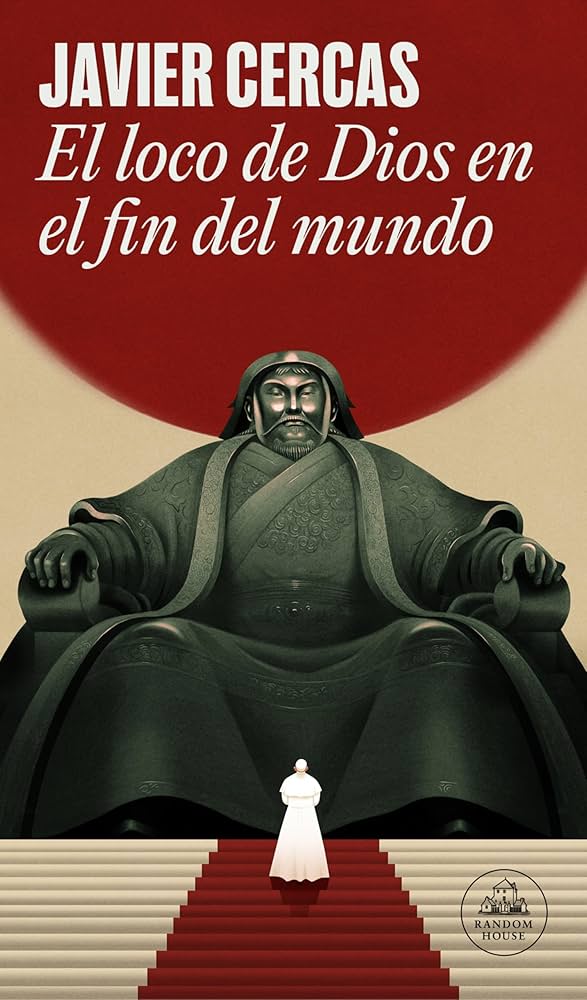

Jorge Mario Bergoglio, an unassuming man from Latin America—a “continent on the periphery,” in Javier Cercas’s own words—became Pope in 2013, and carried out his role without its customary pride, sophistication, and exhibitionism. In El loco de Dios en el fin del mundo (Penguin Random House, 2025), the Spanish writer tells us with transparent feeling of his journey through Mongolia—another political and geographical periphery—and of this anticlerical lunatic’s view of his apostolic task.

The Argentine pope, whose first exhortation was titled “The Joy of the Gospel”—a man who believed God could be found in anyone, even unbelievers, and who achieved absolute harmony with the most pressing matters of the present day (ecology and migration, to name just two)—is the focal point of this book, written by an atheist, a militant secularist, a consummate rationalist, and a thorough non-believer, in the author’s own words. We spoke with Cercas a few short months after the death of Pope Francis about the man who shook the very foundations of an institution that cries out to be renewed.

Natalia Consuegra & Juan Camilo Rincón: Your book was published just a few months before Pope Francis’s death, and it reveals a paradox: his work was praised by atheists, while more orthodox Catholics shunned him for his rejection of a more traditional idea of the Church.

Javier Cercas: I think it’s all a big misunderstanding. He was a disruptive pope for the Church; you might even use the word “revolutionary,” depending on how you understand it. He clearly made no change in Christian doctrine, but there is a revolutionary element to him, which was laid out in Vatican II, the Church’s last great council in the mid-twentieth century. What brings about this revolution? A return to primitive Christianity.

N.C. & J.C.R.: You see Francis as a radical Christian, a radical of the Gospel.

J.C.: The fact is that Christianity means being a radical follower of Christ, and that’s precisely why there was tremendous, fierce resistance against him from certain sectors of the Church. Some people refuse to return to that original Christianity; they don’t like it because they see it as overly radical, or even as something entirely different from Christianity. Francis’s revolution, if we can use that term, came from the fact that all the aspects he sought to change were guided by that return to primitive Christianity. In the first interview he ever gave, he was asked what he wanted to do with the Church, and he said he wanted to take Christ out of the sacristy and put him on the street; which is to say, to return to primitive Christianity. I’m ever more convinced that he was thinking of Dostoevsky, of the story of “The Grand Inquisitor” from The Brothers Karamazov. For that reason, and many others, a portion of the Catholic establishment fervently opposed him.

N.C. & J.C.R.: And because of the notion that he was a leftist, for example.

J.C.: Many people have seen things in him that weren’t really there, and that’s one of them. As Pope, he was radically devoted to the Gospel, and the Gospel is socially closer to the left than the right. Christ was on the side of the penniless: the poor, the outcasts, the prostitutes; he sided neither with the rich nor the powerful. What’s more, he tried to speak to non-Catholics, and he was roundly rebuked for that, but that’s another falsehood; ninety percent of what he said was meant for Catholics. I’ve read everything he wrote, and I can assure you of that.

N.C. & J.C.R.: He was also rebuked for his apparent need to always address those on the periphery.

J.C.: It’s true that, as Pope, he wanted to turn to the peripheries of Catholicism—that was one of his key words—and that’s where non-Catholics are found: that’s why he addressed them, and that’s why, for the first time, an atheist writer like me was given permission to enter the Vatican. The Church had never done that before. Why shouldn’t it have been a Catholic? The answer lies in his vision of the world, which was Christ’s vision as well: he meant to speak to those who were neither Catholics nor Christians. He had what we might call a missionary perspective on the Church, and for him, missionaries are the ones who radically embody the words of Christ. Christianity is radical, and many Catholics don’t like that; they prefer a more moderate, conservative Catholicism, but Christ was no moderate; he was dangerous, and there is a sector of Catholicism that does not accept that. It’s an obvious fact; one only has to read the Gospel to see that this man was dangerous, to such an extent that he was crucified.

N.C. & J.C.R.: How much fiction is there in religion?

J.C.: For atheists, religion might be fictional; for believers, it is not. A non-Christian might say it’s pure superstition, and that opinion is totally respectable. I have sought to understand the true nature of the Catholic Church, of Christianity, now that I have had a golden opportunity to do so. In that sense, coming in with the idea that it’s all fictional means coming in with prejudice, and my primary goal was to set aside all prejudices in order to see reality as it is, to try to understand what those who are really there are saying, from the intellectuals to the pope to prefects, cardinals, and missionaries. I didn’t go there to tell them what I think, but rather to listen to what they told me. Now, rethinking your question: did Francis, unlike other popes, put himself forward as a human being? Is that the real fiction here?

N.C. & J.C.R.: That bothered a lot of people.

J.C.: It bothered the Catholics who wanted a semi-divine pope, one who never made mistakes, who spoke ex cathedra, who prayed for believers because he was going to save their souls, etc. That is all indeed a fiction because the pope is neither semi-divine nor capable of speaking ex cathedra. That’s not true—popes only very rarely speak ex cathedra, when they have to speak on a specific subject, on doctrine. Popes are normal, everyday people, and they make mistakes, they live their lives. Some people cling to papolatry, which means thinking of the pope as an idol. That is obviously a fiction, because the pope is a person. I bring that up several times in the book because it’s very important. The first words he said after he was appointed pope were, “But I am a sinner.”

N.C. & J.C.R.: And you correct him.

J.C.: I correct him sacreligiously: “Because I am a sinner.” The fact is that the Chursh is the home of sinners. Those are not my words; it’s a clear fact, and it’s one we forget. Christ does not choose a Superman; he chooses a Peter, a lowdown fisherman who, what’s more, has denied him three times already. That couldn’t be more meaningful. So the pope is no Superman, that’s not what Christ had in mind. And the fact that the pope has been put forward over the centuries as some higher being, if you will, is also a fiction, because he is the representative of God on Earth. In this case, he approached nonbelievers by putting himself forward as an everyday human being. That’s why he’s called the pope of atheists, which is a huge exaggeration from those believers who are angry with Francis. But it is true that he hoped to speak to non-Catholics, as Jesus did, and he presented himself as what he was: a human being with flaws, virtues, and mistakes. He was a very disruptive pope. Some people said he was a revolutionary without a revolution who accomplished nothing. Well, you might say he accomplished nothing, but the essence of his revolution was the return to primitive Christianity.

N.C. & J.C.R.: And he didn’t come up with that himself.

J.C.: That’s exactly what was said in Vatican II, a council that the whole Church accepts. He took the idea of returning to primitive Christianity seriously; all his efforts at change and reform followed that path. It’s unsurprising that this bothered many Catholics, because there is a great deal of hierarchy, but many everyday Catholics are also accustomed to a form of Catholicism that is, in fact, a perversion of standard practice. I’m not the first person to say it; Dostoevsky, in my opinion, best expressed this obvious fact a long time ago. The Catholicism of the rich and powerful—all that we’ve seen from past popes and soldiers—has nothing to do with Jesus. All of this has caused a great deal of bother, as has the idea of a leftist pope, which is absurd. It is a mistake to interpret him in political terms because it leads you to the wrong conclusions. In certain regards, the Pope was more aligned with the left because the Gospel is more aligned with the left in those regards: the poor, the unfortunate, etc. And there are regards in which the Pope was closer to the right, as far as moral questions, especially abortion, etc.

N.C. & J.C.R.: Did he only complete half of his revolution? You say he understood he would not be able to bring about all the reforms he hoped for.

J.C.: He didn’t only complete half; he was able to complete five percent of what had to be done. Those who don’t understand that do not understand the nature of the Church.

N.C. & J.C.R.: You also write about humor, joy, celebration, irony, and you mention how Francis claimed “eternity will not be boring.”

J.C.: The simple fact of having a sense of humor is disruptive. What do we associate with Catholicism? Doom and gloom. In the book, there is a quote from Cioran that is almost a leitmotif: “Every religion is a crusade against the sense of humor.” That strikes me as disastrous; I am a novelist, and the novel cannot exist without humor. Cervantes—who is our present and future pope—said so: there is nothing more serious than the sense of humor. I agree with that idea, because, having had a Catholic education myself, I associate religion with its flipside, the sense of humor, which is always disruptive, subversive. In Francis, I found a pope who radically vindicated the sense of humor. He once said in Italian to a friend, who did not understand what he meant, “The closest thing to God’s grace is the sense of humor.”

N.C. & J.C.R.: In Spanish, gracia is synonymous with humor.

J.C.: Precisely. In Spanish, a person who is “gracioso” is a person with a sense of humor, and if something has “gracia” it means it makes people laugh. This pope understood that: a connection between the sense of humor and grace, in no uncertain terms. Approaching the Vatican without preconceptions, despite all I obviously know based on my experience as a Catholic, and despite everything I was glad to study before going to the Vatican to prepare to write this book, allowed me to see all of this as a big surprise, from start to finish. Mongolia may be a very exotic place, but the Vatican is much more so. Everything there surprises you, and not for the reasons you might think. All those clichés about the Vatican are just stupid ways to make money, the black masses and so on…

N.C. & J.C.R.: All the dark, macabre theatre of human sacrifices, Nazi symbolism, and orgies…

J.C.: It’s nothing like that. You meet people who really surprise you, but it’s because of things like the existence of a prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith.

N.C. & J.C.R.: You even write about a head intellectual. The Church is interested in relating to all aspects of people’s lives through the official gazette, a journal that addresses political and intellectual matters, even literature…

J.C.: I only call him a “head intellectual” as a manner of speaking. They also have media outlets, which is one of the most surprising parts.

N.C. & J.C.R.: The whole thing is a media outlet.

J.C.: There’s nothing else like it. This machinery operates around the world. It’s astonishing!

N.C. & J.C.R.: But it still clings to a language that, as someone from the inside tells you, even the Vatican itself cannot shift.

J.C.: I see that as one of the basic issues: the linguistic question. On the one hand, the Church uses hermetic language, and, at the same time, the most important word of Francis’s papacy was “synodality.” That’s why all the changes he managed to carry out must be interpreted through the lens of a return to primitive Christianity, of returning to the Christianity of Christ himself. Even still, no one understands the word “synodality.” Nobody knows it, not even Catholics. It’s a hermetic language that no one understands and, on the other hand, it’s an old language, which is even worse.

N.C. & J.C.R.: It’s lifeless, worn out.

J.C.: It’s awful. It has no meaning, no grace. Priests talk in an old way, everything is old. From my perspective, that is a huge, basic, colossal problem, and one that I don’t know how to fix, because it’s apparent that Christ’s Christianity was disruptive, with a language that broke barriers, a language of the streets that was completely unexpected, that led him to have the incredible impact he had—no one has ever made such an impact, precisely because of his new language—so why this old, completely uninteresting language? That’s the problem that nobody talks about, not even Francis. I think that’s the main problem.

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon