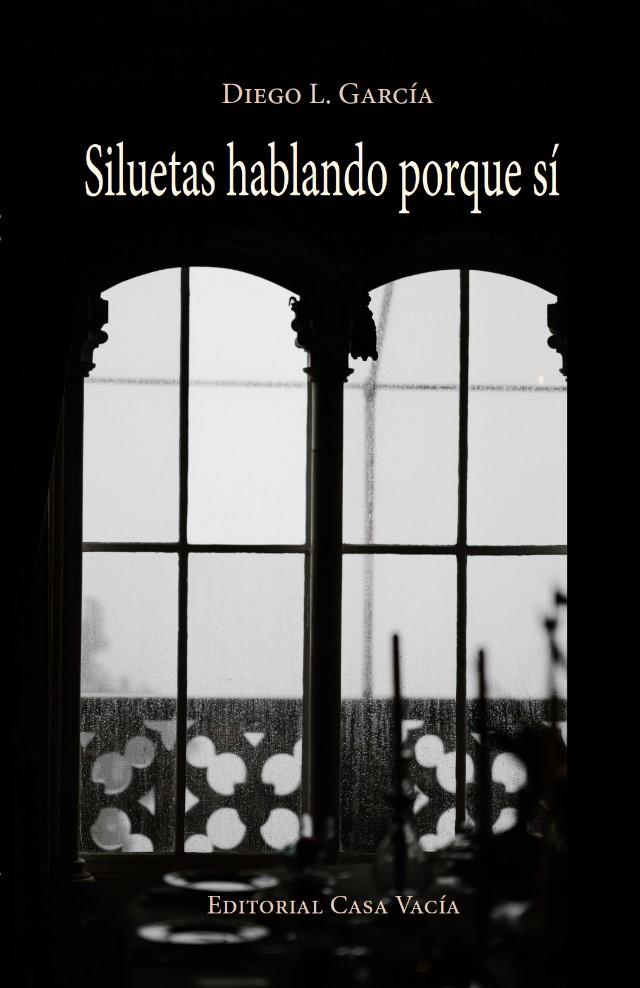

United States: Editorial Casa Vacía. 2022. 64 pages.

A superficial reading makes us think about pulp poetry, film and urban pieces; glimpses made for the big screen from either a movie theater or visions from our own streets, in broad daylight or in one-night prolonged intervals. I have tried to view this piece from a standstill and from the first moment I literally dropped the ball. I shouldn’t view this book from a conventional unity; this unity I see now was built from fragments that aren’t entirely organized: “solo son flashes/ que lo cortan todo sin motivo” [they are only flashes/ that cut everything up for no reason], says Argentine poet Diego L. García, author of Siluetas hablando porque sí (Editorial Casa Vacía, 2022).

A superficial reading makes us think about pulp poetry, film and urban pieces; glimpses made for the big screen from either a movie theater or visions from our own streets, in broad daylight or in one-night prolonged intervals. I have tried to view this piece from a standstill and from the first moment I literally dropped the ball. I shouldn’t view this book from a conventional unity; this unity I see now was built from fragments that aren’t entirely organized: “solo son flashes/ que lo cortan todo sin motivo” [they are only flashes/ that cut everything up for no reason], says Argentine poet Diego L. García, author of Siluetas hablando porque sí (Editorial Casa Vacía, 2022).

Diego L. García (Buenos Aires, 1983) is a poet, essayist, and professor of Letters who graduated from the National University of La Plata. Before releasing Siluetas hablando porque sí, he was known for the following works: Fin del enigma (2011), Esa trampa de ver (2016), Una cuestión de diseño (2018), and Las calles nevadas (2020). He often collaborates with online magazines in Latin America. Among those are Periódico de Poesía (Mexico), Vallejo & Co. (Peru), Jámpster (Chile), and Poesía (Venezuela).

Perhaps it comes down to the same set of symptoms José María Valverde expressed in the first pages of his book La literatura: I stop seeing the poem’s actions and I dissolve in its fading words. The Spanish translator and writer was referring to a deformation as readers, when we reach a certain verbal awareness that can turn out to be unfavorable. Others call it professional deformation. If I transport this feeling to the book we’re talking about now, by Diego L. García, I think of possible poetics; meaning, for what each poem expresses and for the theoretical insights that can be read between the lines: “ni la belleza ni el poema/ necesitan que las cosas se completen” [neither beauty nor the poem/ needs for things to be complete].

Here I list some formal traits that those who read Siluetas hablando porque sí will notice: poems that are almost always brief, some with titles, others without; using punctuation between verses but not at the end of the poems; omitting capital letters after a period and what follows; using only the closing question mark (as in English). I go quickly or slowly through this book: and I’m allowed both tempos. The syntactic life of poems reflects the life described within them. The poet, although not always deliberately, moves his characters as they would move in a North American film. Rather than a single film, they would be scenes conveniently taken from several films and compiled into an album with newspaper clippings, either from the Events section or from the Society section.

The poetic self that is present serves as an amateur film critic, such that when reading the poem you may think, “I don’t believe it.” The problem with these types of unions is that the bias toward what is realistic is very much alive: what I read must align with my insights or mental representations. This is a personal error: it’s not about logical or descriptive sentences, but rather about verses that make up the image in full, including giving space to certain images which aren’t at all favorable to a palate of “good taste.” That is where the anti-poetic emerges in some of the final works chosen by Diego L. García: a sudden cut, rustic yet not weak. These poems bring about a sustained flow of anecdotes. It’s nice to feel this way: to read poems that say what they need to say but with a very natural flow. There is also space to “think” in the poem. I’ve noticed that Diego pauses to reflect as a conclusion, that something denser than normal is concentrated into the last verses of each text: “la oscuridad nos revela/ una verdadera libertad” [darkness reveals to us/ a true freedom].

I look more closely at these poems and their distant associations, as Reverdy calls them, and they start to draw out “closer” strokes. What I first perceive to be a grand piano turns into a computer. Or is it the other way around? “Con las teclas blancas y negras escribe/ un relato de lo que acontece” [with the black and white keys he writes/ a story of what is happening]. While I become more paralyzed, while I let my eyes work with my still body, other spaces emerge in the book.

I tend to go for the poems that are in between fronts, those that try to meticulously crumble the notion we have of lyric poetry. It’s no longer about going to the other side of meaning or the generic, or opposing the design of the contemporary poem. I’m interested in the dissident collection of poems; I’ll explain: the collections of poems which avoid, wherever possible (and if the poet is demanding, it can always be possible) the common twists and turns. Just as what is commonplace or wasted can result in being counterproductive, unwarranted “efectismo” [sensationalism] is also displeasing.

A writer friend would call a small book of microstories a “novela corta” [short novel]: a pulverized, atomized novella. Similarly, I think Diego L. García has built a “novela corta” [short novel] in verse, shredded. Nonetheless, these fragments keep beating while the poet narrates, enumerates, or describes. Although what we end up reading is a book influenced by other antecedents or subgenres (among those, pulp novels or pulp fiction, Richard Ford, Marty Holland…). One can certainly notice a reader avid for other styles in an exercise of healthy appropriation: “nada más simple que una llamada telefónica/ que fracasa porque al otro lado/ nadie quiere participar del crimen” [nothing simpler than a phone call/ that fails because on the other end/ no one wants to partake in the crime].

Daniel Freidemberg, who worked on writing the words on the back cover, has described this poetry as a “montage of captures.” And it’s nothing different from what we, as recipients of this book, perceive. What is captured demands its own method, a special kind of calisthenics. Diego L. García, in all awareness, has also created a bridge towards other thematic interests. This is a success we should appreciate and treasure.