During my adolescence, Los Redondos (that’s how Patricio Rey y sus Redonditos de Ricota were known colloquially) were an obsession and a mystery. They only gave interviews every once in a while, and going to hear them live implied a real risk because of the violence and police repression that had begun to take place around their concerts. They didn’t make TV appearances and there weren’t any film recordings of their concerts. Additionally, their lyrics weren’t linear, but they impacted me, as well as many young men and women of my generation (and others, as well), in an inexplicable way. The band had formed in the mid-seventies, during the dictatorship, and their first concerts were sporadic, like a space of artistic and psychedelic resistance during a time when repression was common currency. There were artistic performances that included live chickens on stage, scantily-dressed girls, monologuists, and a chaotic rock-n-roll. They had an unusual name, referring back to oldies artists like Bill Haley & His Comets. No one could imagine, at that time, that they would transform into the most compelling band in Argentina. Although it would stay up-to-date with the digital revolution, the group always maintained a musical identity linked to epic rock. On a road plotted outside of corporate show business, Los Redondos raised the flags of independent music (and of the entertainment industry). They made their way through the underground of the early eighties, and after appearing at discos, they arrived at Estadio Obras, a closed venue for some five thousand people, which they got used to filling up without interruption. The nineties were the decade of great stadiums and touring through towns in the interior, which were practically overrun with fans, comparatively devoted, perhaps, as followers of the Grateful Dead in the United States. The mysticism of the Redonditos de Ricota was (is) inexplicable: probably on par with Peronism, the most important social and cultural phenomenon in Argentina in the twentieth century.

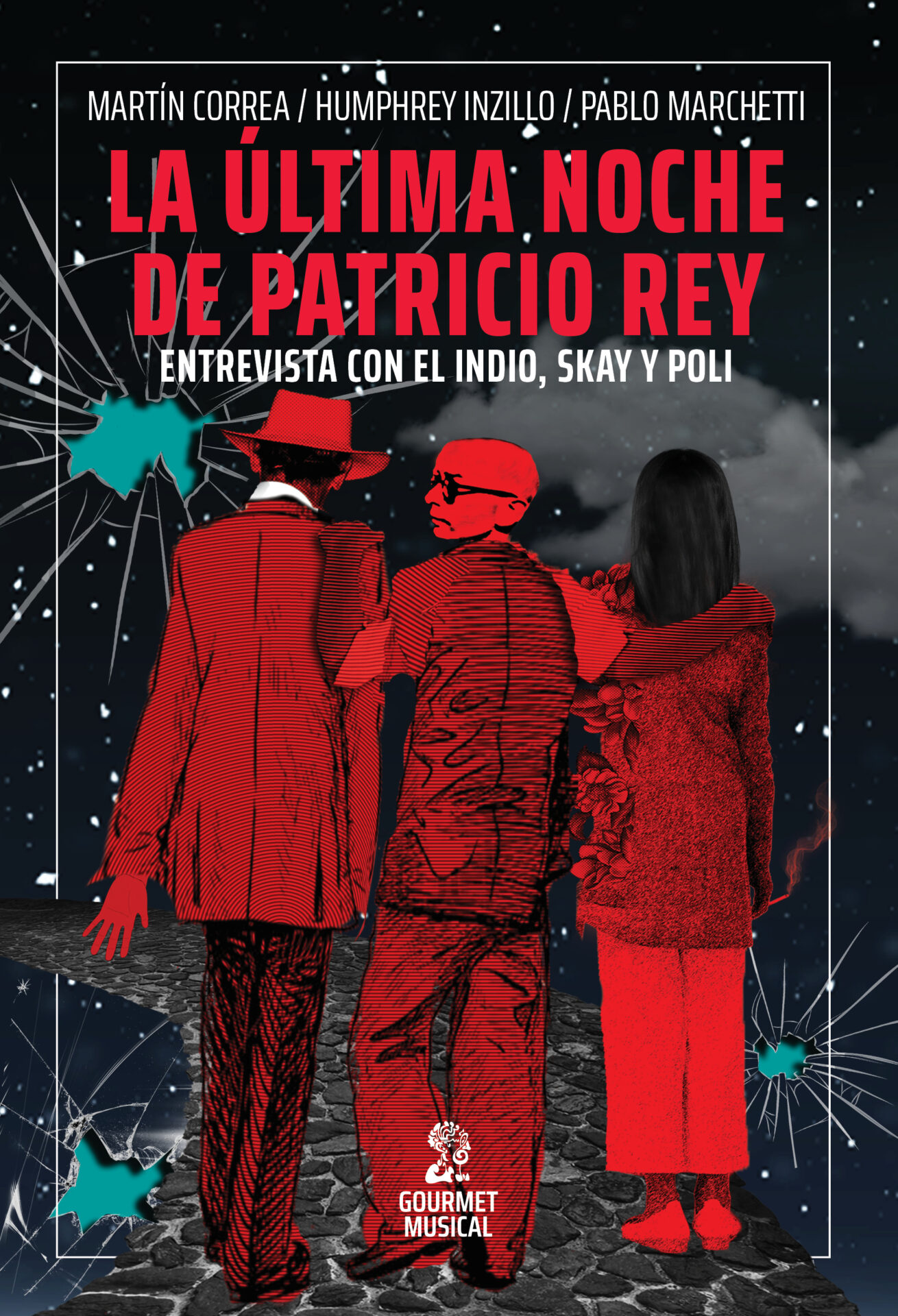

At the start of the new millennium, in my first steps as a rock journalist, I had the opportunity to interview them three times with my colleagues at an independent magazine called La García. The third of those interviews was the last one given by the core of the group, the songwriting duo made up of singer Indio Solari and the guitarist Skay Beilinson, as well as their manager, La Negra Poli. After six hours of conversation and with a monumental amount of alcohol in our blood, we said our goodbyes at a corner in the Palermo neighborhood of Buenos Aires. We saw them walk away, drunk and with their arms around each other, presumably happy. Minutes later, an argument due to old complaints between the singer and the manager would devolve into the fight that would put an end to an artistic enterprise that had lasted a quarter of a century. Years after the dissolution of Patricio Rey y sus Redonditos de Ricota, we found out we had been the authors of the group’s last interview. And, perhaps more important than that, we had been witnesses to the last time those three people, creators of the powerful cultural artefact that changed our lives, had been in a state of harmony. The complete story is narrated in La última noche de Patricio Rey, the book published by Gourmet Musical Ediciones, twenty years after that sad, lonely, and final evening.

Translated by Luis Guzmán Valerio