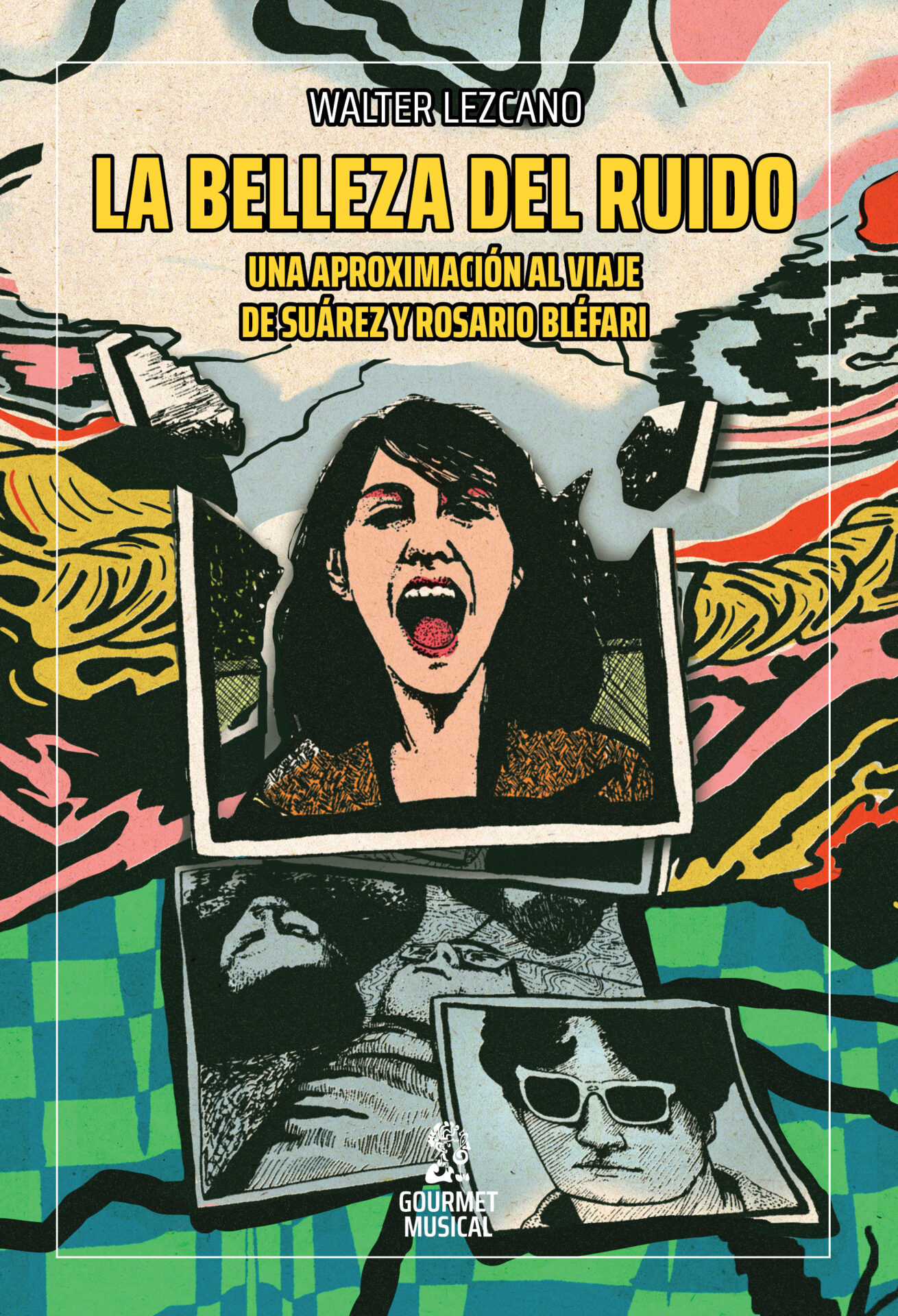

“Asesina!” Rosario Bléfari yelled on that night from the stage in front of the largest audience in Suárez’s existence.

In that song, titled precisely “Asesina,” which could form part of the soundtrack of any Tarantino film, it is said that the body speaks and that it must be heard. Bléfari, in keeping with her words, listened to her robust body and didn’t hide her pregnancy: she carried it like a flag of existential independence during the entire concert and she yelled “Asesina!” once again.

From down below, some—very few, according to attendees at that concert—called her, “Puta!”

On February 4, 2001, the Festival Argentina en Vivo 2 took place at the Club Hípico de Palermo. There were eight bands and soloists (Daniel Melero, María Gabriela Epumer, Leo García, Turf, and Los 7 Delfines, among others) with the aim of being a sort of—very partial—map of and guide to the sonic and alternative scene that dominated one of the currents and manifestations of Argentine rock during the nineties.

It could have been another festival, lost in the cloudiness of memory. A speck in the almanac of days where it would be a lot of trouble to attribute to it any distinctive feature. And, still, it had one.

On that night, Suárez went up to play: an extremely strange and unique band in a country that was about to fall apart a few months later.

But what was unforgettable about that night was deposited in a body, and—more than anything—in an attitude: Rosario Bléfari went up to sing pregnant, with her proud belly exposed and in a state of grace, of enchantment, entirely hypnotic. It’s on YouTube. Anyone can watch it.

After ten years leading her band, and when it wasn’t very common in Argentina to see a woman in that position, Bléfari deployed on that night all her charm, in different senses of the term: from the visual to the musical, the aesthetic, the political, and the poetic. Of course, the twentieth century was just coming to an end and her performance was not well received by a portion of that audience. Those were the days.

The question that circulated was this: how does a pregnant woman dare to sing rock songs with that self-confidence and that agility, shouldn’t she be resting? Isn’t she, in a lot of ways, mistreating her future daughter and degrading her status as a mother?

Rosario Bléfari—always adventurous, iconic, and empowered—didn’t pay attention to any of these burning criticisms (very upset men and women) and kept on with her life on stage: she finished the concert as planned. A little later, Suárez would come to an end, and she would kick off her solo career with the album Cara (2001), which was originally envisioned as the band’s next release.

This is how the place from which she always worked is revealed: from the future. She moves onward. And from there, a tomorrow in which the world is more just and beautiful, she is still speaking to us.

Translated by Luis Guzmán Valerio