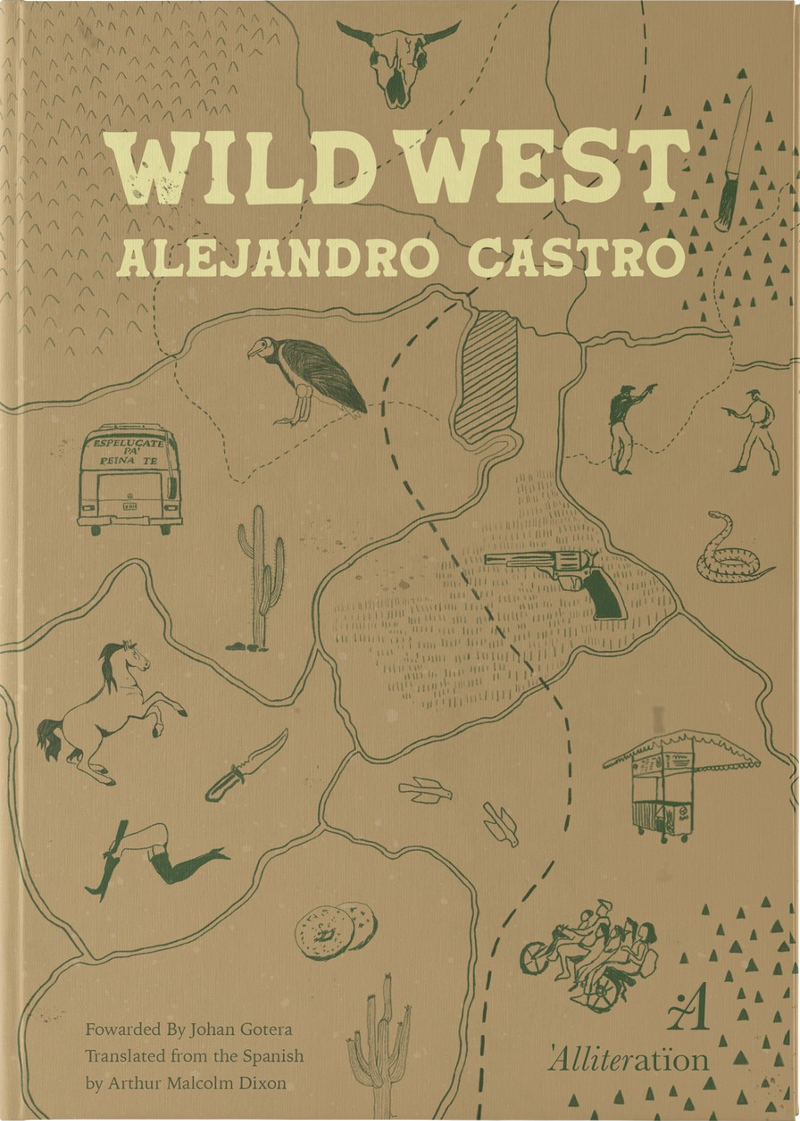

Editor’s Note: Wild West, the translation into English of El lejano oeste (bid&co, 2013) by Venezuelan poet Alejandro Castro, translated by LALT Managing Editor Arthur Malcolm Dixon, is available now from Alliteration Publishing.

Casalta

I’ve got to survive you

in amongst the dogs at dawn

who sing the songs of hate.

Under bullets over city

day after day Casalta I’ve got to survive you.

But I bear you with me Casalta come what may

with diapers on the balcony and sidewalks

your feigned joy and the sound teeth make in the cold

or could it be in fear of closing the door

and the dog pack the gunshots and merengue

infiltrating through the cracks

as if you did not mind being forevermore deforested

and turning on the government-handout light bulbs

to forget.

I want to leave you here Casalta in the poem

brick you up in childhood rubble.

Me—my brother and I—guessing

the color of the cars in which my father was not coming

making up songs for the blackout

surviving you miraculously

behind the bars.

Song for Bolívar 1

Now that everything has your name on it, Bolívar,

and that’s no metaphor,

let’s put things in their place.

Miranda did not die of bochinche—you killed him.

And Colombia grew greater gorged on misery.

And the Olympus we raised up

in praise that you might reign atop it

is one endless slum.

And now

you’re into coming back to life or reincarnating

not one soul is unallergic

to your name and that, Bolívar,

is no hyperbole.

Your name is an alibi,

a bill plucked from the mud, worthless,

yet another busted square,

a corner.

Your name is a landlocked country,

the highest peak of the poorest range / on earth.

The only glory in your name, Liberator,

is a street of clacking heels

size twelve.

03-02

for Guillermo Vargas

Across the hallway lives a witch

who has spent her life wondering

which heaven sends the sax down on Sundays

so much baffling jazz to set the scene

for conjuring such blues such Satchmo

gritty in the clacking of the fingers

summoning death.

Heaven is audible from hell.

It finds its way to you as well transparent from

her door the obscenity of ash

from candles lit to who knows which

virgin suicides.

There is no better description of our homeland

than the five infinite feet between your

door and hers: in my country

heaven and hell are neighbors

infecting each other like on the third floor.

III

for Gerardo Rosales

Daddy, when I grow up

I want to be a pansy.

They might like the cold, but look how colorful

they are! Look how they take the shapes

of hearts and faces, and how gracefully

they wither as the earth dries up.

Daddy, when I grow up

I want to be a fairy,

flitting winged

on a diet of dust

until the last believer

loses faith in me.

Daddy, when I grow up

I want to be a queen:

to reign supreme

until a blade takes off my head.

I want to be something pretty and dead

from the last storybook I’ll ever read.

VI

I will feel this poem up.

I will lick it, lie to it, lose

my head over this poem like it was

a man.

I will stare at its feet,

check out this poem’s package as

if it were flesh.

I will ignore the warning signs, won’t know

if it is love or lust or boredom

bringing me down to my knees before this poem.

And I will not look up at its heart:

I like this poem waist-down.

This poem has no heart and mine belongs

for now to the boy at the orange stand

juicing.