On the publication of the book La librería y la diosa by Paula Vázquez, our Translation Editor Denise Kripper chats with the Argentine writer and bookseller.

Denise Kripper: La librería y la diosa tells the story of two transformations, two stories marked by desire: leaving the first, family home; and building a new one. Books punctuate the narrative, both of becoming a bookseller, and a mother. What’s the relationship between the fertile and communal literary space that the bookstore Lata Peinada opened up for you and the fertility challenges that you faced in your path to motherhood?

Paula Vázquez: Your question already contains the root of my answer. At the beginning, the bookstore appeared in the text only as the daily background that witnessed the story of my quest (and losses) that marked the beginning of my motherhood process. But then I had an epiphany: the bookstore had been an essential part of the discovery of a new kind of desire for me, a new way of living, where there was indeed a space for becoming a mother. That’s why in the book there are ultimately three threads: the opening of the bookstore, a reflection on pottery, and the desire for motherhood. In these three elements, the collective, the communal, and the genealogical are key.

D.K.: Lata Peinada was founded with the explicit goal of bringing to Spain the catalogs of independent Latin American publishing houses, that is, books that are otherwise not available there. The bookstore then offers an “arrow in the opposite direction of many ships for hundreds of years.” I’m interested in learning more about how we’re being read in Spain, and more specifically in Catalunya. Is the main audience of the bookstore Latin Americans who live there, or is there a local audience interested in its offerings? Who are some of your bestselling authors and why do you think that is?

P.V.: There are many Catalonians, and Spanish people in general, as well as other Europeans who live in Barcelona or who are simply passing by, who are regular customers or come specifically to visit us. In the last few years, there has been a growing interest in Europe in Latin American literature, although it’s not uncommon for labels to come up that reduce very different writing in our continent to certain phenomena. The exoticizing of violence could be one of the current reductionist lenses of the times. That’s why our project seeks to always open up that viewpoint and engage in the circulation of diverse writing, both contemporary and from the past. What sells the most can be pretty eclectic. This year, for example, one of our bestselling books was El cielo de la selva by Elaine Vilar Madruga. She’s a fantastic writer, and very prolific too, so I’m sure we’ll have more books by her soon. But in this case, the value of this novel was recognized. Babelia even included it in their classic, annual ranking. Also a bestselling book was La compulsión autobiográfica, an essay by a Mexican author called César Tejeda, published by Alacraña, which we brought specifically for our book club. That’s where our work of spreading the word comes to fruition, when a good book finds new readers.

D.K.: In this memoir there’s also a lot of reflection on the book as medium, on the writing process, on naming as an exercise. The literary workshop by Fabián Casas you attended is key in this regard. Referring to poetry, you remember him saying “a poem needs to create a state of uncertainty, not an answer.” And your book indeed is full of uncertainties. Everything is a gamble: opening a bookstore in another country, bringing a child into the world, even putting a pottery piece in the oven. How can we “make room for uncertainty” in this time and era?

P.V.: It’s always an exercise, a question. In my case, it was first about dismantling a very strong rhetoric around control, certainty, definitions about the world and my own life. We are living in a time very much marked by definitions of who we are, so the challenge is, once again, an opposition exercise, not without resistance, of finding an edge to open up a space, expand the label of what’s our own and do some digging in the collective, in all that surrounds us, and what came before us. Identity can be a poor experience. It’s not about jumping into the void either, it’s really about finding a behavior away from the rationality of productivity, but maybe it doesn’t need to be defined or named, and that’s how it can keep the mystery, or as Fabián used to say, the uncertainty required by poetry.

D.K.: Mishal’s pottery workshop is the other key space in your book, one that inaugurates the possibility of creating in silence. It’s in this space, prime for listening, that you first allow yourself to verbalize what was going on with you, open up about your miscarriages, and find a different reaction in those around you. At several times in the book, you mention your inability to write, to move forward with the diary you were keeping. I wonder then about those spaces, pauses, silences. What did those moments allow you to write later on?

P.V.: Writing is so paradoxical, because it implies silence and words, listening and voice. But in the face of certain very painful events that created deep breaks in my life, such as the death of my mother or my miscarriages, my writing only came to me in fragments, like remains of a lost world. In those moments, I needed to seek refuge in my body, go to yoga, or do pottery in this case. I don’t assign much weight to silence in those settings but to the turning on of the body’s potency, which puts things forward both in the world and in my life.

D.K.: Your pottery practice goes hand in hand with your motherhood, linked by common threads: care; patience; frustration; what’s yours, made by you, but yet is something different, new. I think about your pottery pieces on display in your home, but also other everyday objects that served an analogous function: your aunt’s inaccessible books, your mother’s tablecloths, your niece’s jacarandas. Tell me a little bit about your relationship with those objects around you.

P.V.: Yes, I keep and care for objects and plants as if they were amulets. I assign them power or essence. It’s kind of embarrassing to describe it in those terms, and I’m also not sure what it means to do so, to have embodied material elements around me. It’s a kind of inventory of roots, of important moments; foundations of my life that can take shape in anything: a shirt that belonged to my mother and which I wore to her funeral because I was all out of clean clothes, a gold-leaf glass jug which belonged to my great-grandmother, a huge agave named Pocho, the sculpture of the goddess, the dictionary I received as a present for my sixth birthday. I think my tattoos also work in that way.

D.K.: And speaking of objects, in Lata Peinada there is a section devoted to “gems,” which includes first editions, impossible-to-find books. What are some of the gems on your personal shelves? What books relate to your emotional relationship and your indestructible bond with books?

P.V.: My dictionary, the red-cover Pequeño Larousse Ilustrado, which I got for my sixth birthday, some first editions of Plástico cruel by José Sbarra; of Extracción de la piedra de la locura by Pizarnik; Borges by Bioy; of Los pichiciegos by Fogwill; of El affair Skeffington by María Moreno. I used to have a first edition of Obsesión del espacio by Ricardo Zelarayán, author of Lata Peinada, an amazing poetry collection, and I gifted it to Caetano Veloso this one time I had to present him with an award. I’m now looking to buy another copy again, but I haven’t had much luck yet. I also have books that I love because they’re all underlined and because they remind me I found in them something that shook me: Las palmeras salvajes by Faulkner; Cien años de soledad by García Márquez; La furia by Silvina Ocampo, and more recently, I can name Apolo cupisnique by Mario Montalbetti; A lo lejos by Hernán Díaz; and La cresta de ilión by Cristina Rivera Garza.

D.K.: In La librería y la diosa you discuss recommending books (a daily occurrence at a bookstore) almost like an act of love. What are the books you currently recommend and why?

P.V.: El cielo de la selva by Elaine Vilar Madruga, a very prolific, unruly author, who creates very peculiar universes, and whose language is always excessive, effusive, joyful. She has a previous novel (published in Spain with a prologue by Cristina Morales) called La tiranía de las moscas, which is also great. A lo lejos by Hernán Díaz, is a novel deeply rooted in the Argentine literary tradition, and it’s a lot better than the more celebrated and award-winning Fortuna. Limpia by Alia Trabucco Zerán, a Chilean author who will undoubtedly be among the best things we’ll read in the future. El occiso by María Virginia Estenssoro, and La amortajada by María Luisa Bombal, both recently republished, are essential readings as predecessors of Latin American fantastic literature.

D.K.: In November of 2023, after almost three years, the Lata Peinada branch in Madrid closed its doors. In the book, your business partner Ezequiel Naya suggests the idea of opening a branch in Buenos Aires, and you both entertain it. What’s next for the bookstore?

P.V.: We’re going back to the clay, to our beginnings of friendship and literature. Let’s see where we find our fire again and what the result of that is this time.

Translated by Denise Kripper

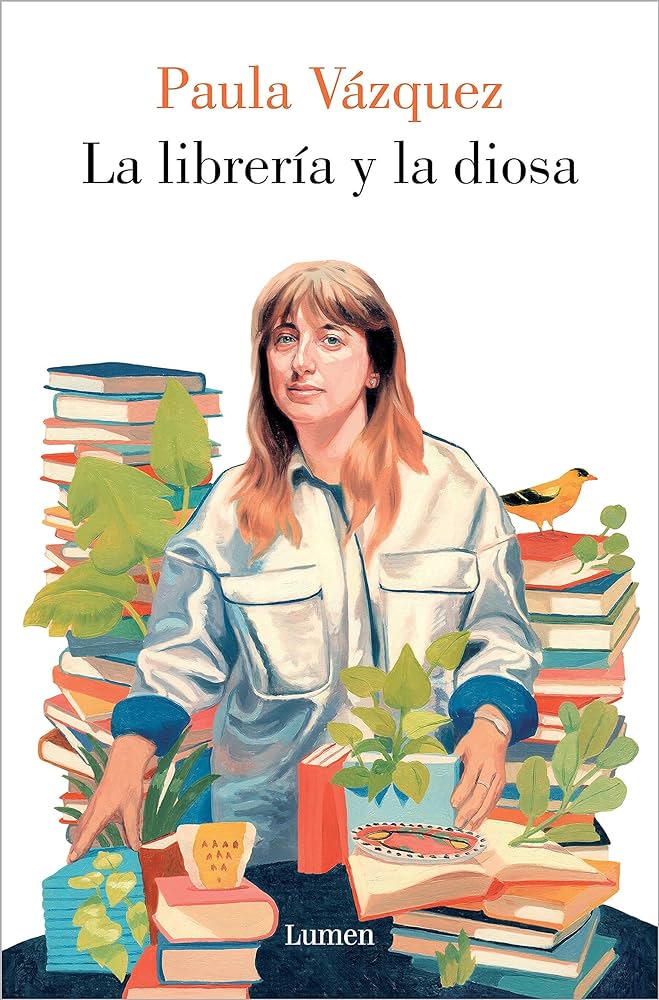

Photo: Argentine writer and bookseller Paula Vázquez.

Paula Vázquez (Provincia de Buenos Aires, 1984) is a writer, bookseller, and cultural manager. She’s the co-founder of Lata Peinada, a bookstore devoted exclusively to Latin American literature in Barcelona. She’s the author of the short-story collection La suerte de las mujeres (2017) and the novel Las estrellas (2020). Her work has appeared in Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, Infobae, Pliego Suelto, and Revista Crisis, among others. La librería y la diosa (Lumen, 2023) is her latest book.