famous authors of brazil

Brazilian Graphic Novelists

Gabriel Bá

The term “graphic novel“ is still unusual in Brazil. Two main factors might explain its unusual character:

1. As a genre, the graphic novel has to deal with the obvious but not so easy to answer question: is it literary?

The constant need to ask if the graphic novel is or isn’t literary has to do first with its interdisciplinary nature. To ask if a visual object can also be literary seems to be a more effective approach to the validation or rejection of the graphic novel in the traditional literary agenda.

2. The form in which the graphic novel manifests its interdisciplinary nature is often associated with comics or the visual language of young adult books. This common and generalized association between both worlds and the unfortunate conception of young adult books as an inferior type of narrative denies the graphic novel what it has deserved since its appearance in the seventies: a place in academia, literary and inter-semiotic studies, and our bookshelves.

In Brazil, there are few but very interesting cases of authors who decided to create interdisciplinary works against all odds. The continued effort to create a simultaneously verbal and visual object that is as complex as traditional novels and the effort to intersemiotically translate a verbal object into an image are now starting to pay off.

Rafael Coutinho and Daniel Galera (Cachalote, 2010), Odyr and Angélica Freitas (Guadalupe, 2012), Lourenço Mutarelli (Diomedes, 2012), Shiko (Azul Diferente do Céu, 2013), Diego Sanchez (Perpetuum Mobile, 2013 and Hermínia, 2015), Magno Costa (A Vida de Jonas, 2014), Marcello Quintanilha (Tungstênio, 2014 and Talco de Vidro, 2015), Psonha (Pogando, 2015), Ana Luiza Kohler (Beco do Rosário, 2015), Felipe Portugal (Espiga, 2015), Carol Rossetti (Mulheres, 2015), Germana Viana (Lizzie Bordello e as Piratas do Espaço, 2015), Juscelino Neco (Matadouro de Unicórnios, 2016), and Marcelo D’ Salete (Angola Janga, 2017) are some of the names that have stood out among graphic novelists.

Among them, the work of Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon distinguishes itself for its creativity and literary innovation. It also reminds us that the analysis of graphic novels should utilize the interpretative tools and skills used in the analysis of traditional novels or artistic objects. At the same time, their work also shows us how much those same interpretative tools need to be amplified.

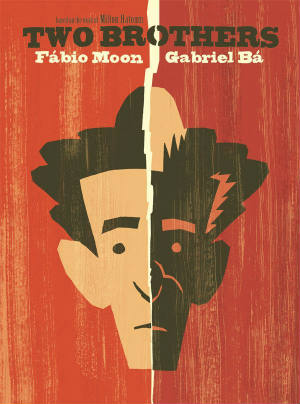

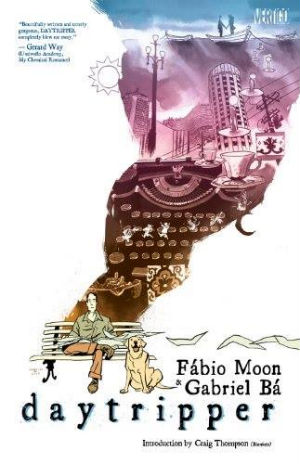

In addition to adapting two literary and canonical works—O Alienista by Machado de Assis and Dois Irmãos by Milton Hatoum, in 2007 and 2015, respectively—in 2011, Bá and Moon released the complete version of Daytripper.

Patrícia Lino: Would you describe yourselves as readers first and authors second? Readers of whom?

Gabriel Bá: I think reading comes first in life. First, we need to read before we want to create. We read comics and many books before wanting to tell our own stories. Those books and graphic novels were the ones that made us want to do it.

Fábio Moon: When we were only readers, we would follow the characters. We would read super hero comics, Garfield, and Mad magazine satires. It was only when we discovered some works in which someone had done that—someone had written it and the someone else had drawn it—that we came to realize we could do the same as well. It was possible for us to be authors.

GB: Frank Miller, author of The Dark Knight and Ronin, stood out as an author who had a voice among the super hero comics we would read. A magazine called Chiclete com Banana also appeared in Brazil, through which we got to know the work of Angeli and Laerte, great Brazilian cartoonists who had a great influence on this idea of an independent author who makes everything: writes, draws and has his/her own magazine.

GB: Frank Miller, author of The Dark Knight and Ronin, stood out as an author who had a voice among the super hero comics we would read. A magazine called Chiclete com Banana also appeared in Brazil, through which we got to know the work of Angeli and Laerte, great Brazilian cartoonists who had a great influence on this idea of an independent author who makes everything: writes, draws and has his/her own magazine.

PL: You have an obvious interest in narrative; as if drawings needed words and as if both needed to be created with the idea of a reader in mind. Would you say your work is, apart from this, a narrative intersection between the visual and the poetic (the latter in connection with the comparison Fábio makes between comics’ language and poetic language)?

GB: Since the beginning of our career, we’ve felt the need for a story guiding the drawings. A lot of people get interested in comics because of drawing and we aren’t an exception, but without a story our drawings lose their appeal, their goal. The story carries the reader through the pages and it’s also the story which brings him/her back to a new chapter.

FM: We like to think that a comics story can be developed on different levels. There is a visual level, in which the drawing tells something, and another informative and textual level; there’s also a third level—the result of the first two. When this third new level exists in the reader’s head, the subjectivity of the reading makes countless levels for the same story. Words are more than mere words and images are more than images. When we realized that, in those stories, with all these layers the reader would get much more involved, by having an active role in the construction of the meaning of the story, we discovered in comics a type of creation different from other narratives, and that grabbed our attention and inspired us to follow that path.

PL: Would you say this interest of yours manifested itself for the first time in the inter-semiotic translation of two literary texts (O Alienista and Dois Irmãos)? Besides the fact that Machado de Assis is dead and Milton de Hatoum is alive, was there a difference between illustrating (or translating) the narrative of a dead author and the work of a living author?

FM: Our interest in the story began way before, in high school, when we read books like Capitães daf Areia by Jorge Amado or The Building by Will Eisner. Throughout the years, we came to understand how writers have a particular way of writing, an original voice. Authors such as Machado de Assis, Guimarães Rosa, José Saramago. It was our admiration for their voices that led us to the adaption of O Alienista by Machado, an opportunity to put his style and the language of comics together. Later, the same happened with Dois Irmãos. We accepted the challenge of telling the story, keeping Milton’s voice and putting it together with ours.

GB: There was a dialogue between Milton and us, even if it was small, during the making of our book. We talked with him in the beginning and we followed his advice about a trip to Manaus, which people to talk to, which places to visit. In the middle of the process, we showed him what characters looked like, and Milton corrected us regarding a character named Zana, her essence, her importance in the story. Besides that, he only saw our work after it was done. He is, however, one of the best advertisers for the book. We gave many talks together, and we always learn a little bit more about the story and about what it means to be a writer with Milton.

PL: Beyond the practical goal of finding more readers for Machado’s work, does the inter-semiotic translation of a canonical text like O Alienista have a creative objective (such as, for instance, amplifying the possibility of interpretations? Or the opposite: reducing them)? What is involved when developing a literary text from a visual perspective?

FM: Each language has its particularities, its qualities. We try to see what we like the most in the original text, what the author’s style, his/her voice is like, and we try to keep it. We only adapt authors we like to read, we believe it’s important to keep what defines them as authors. That said, we study what will be transformed in the adaption, what will be visual and not verbal, and those decisions are the most creative part of our work, because images can substitute descriptions of places, people and actions, but they also can add more layers to the story, more details, more narrative interpretations.

PL: The term “graphic novel” isn’t used very often in the context of Brazilian literature and, often, the genre isn’t even considered literary. How would you explain this academic-critical resistance to this genre? What would the integration of graphic novel in the literary context imply (a more interdisciplinary critical system, in which the critic would have a more interdisciplinary education)?

GB: Comics stories are generally seen in Brazil as literature for children, to entertain, and this image is the direct result of the enormous presence that magazines like Turma da Mônica, by Maurício de Sousa, have had in the market since the sixties. For many years, comics authors followed various and more popular genres, like terror or humor, always with the intention of entertaining, of criticizing (something we inherited from cultural production during and after the military dictatorship). Only very recently are Brazilian authors looking for longer, more serious, and deeper narratives, which can be called graphic novels. The real truth is, despite the fact that comics started to be produced at the end of nineteenth century, we still don’t have a graphic novel tradition, we don’t have any classical works produced more than ten or fifteen years ago. Maybe the oldest and most relevant is Diomedes, a trilogia do acidente, by Lourenço Mutarelli, published between 1999 and 2002.

FM: The union of the literary world and the world of comics in Brazil is a little less than ten years old—where we can see interaction among authors and the presence of one in an event for another and vice-versa. This movement happened after Lourenço Mutarelli published his first novels (O Cheiro do Ralo and Natimorto), after Rafael Coutinho published his graphic novel Cachalote, together with the writer Daniel Galera, and after Bá and I won the Jabuti Award with our adaption of O Alienista by Machado de Assis. Before that, both worlds were totally different, separated, with no connection at all.

PL: Your work, besides being literary, is also philosophical. Death is one its central subjects, especially in Daytripper. How would you explain your constant interest in the subject of death?

PL: Your work, besides being literary, is also philosophical. Death is one its central subjects, especially in Daytripper. How would you explain your constant interest in the subject of death?

GB: Our biggest interest is human existence, human relationships and the beauty we can find in small things. However, in order to pay more attention to such ordinary and mundane details, we need a bizarre, strange element, something that grabs the attention of the reader and makes him/her perceive all those things that he/she tends to ignore in daily life. Death has that power, it’s the element we use to show that, one day, everything that is here will be gone. When you think about this, everything changes and gains a new value.

FM: When we work on an adaptation, the story is already there, and our role is to choose the best way of telling it by using the specific language of comics. It’s about constructing and re-constructing. But when we tell an original story, the story was already imagined visually, in the space of the page, in the movement of turning it. Comics is a visual and a spatial language, where you control the space which the narrative will be occupying, the velocity with which the narrative crosses pages, the quantity of information which goes in each page. It isn’t only about the pure story, but about its form.

PL: Daytripper is a magic group of short stories about Brás, connected by the subject of death. How would you comment on this idea if I told you I thought of the expression “short story” as being connected to an increasingly cathartic and explosive structure?

GB: Daytripper is a story which was built to work through chapters because, to begin with, we published it as a series in the United States. Each chapter should work by itself, independent from the others, but making sense when read side by side with others. With all the chapters together, we have been building a big jigsaw puzzle that represents Brás’ life, with the people who are part of it, with his choices, joys, and sad moments.

FM: The separate chapters have an individual force, but collectively they become stronger as the story progresses and the experience of reading intensifies when you read the complete story. We had readers who followed the publication each month, for ten entire months, but the majority of our readers read the collected story and can read it in a sitting, commuting, during a break, in bed before going to sleep. It’s a more intense experience.

PL: How would you describe Brazilian graphic novel nowadays (for instance, what other authors would you recommend?) and how do you see its future (in the market and in the academic/literary context?)

GB: Generally, the Brazilian comics author is a reflection of what is published in Brazil. Even if he/she has access to Internet and international works, it’s what they see at kiosks and in bookstores that leads them to develop their repertoire and want to tell their own stories. Taking that into consideration, today we have a much more diverse market, with several publishing houses printing an enormous variety of works and genres, which results in a new generation of comics authors with a lot of diverse projects. The Brazilian graphic novel is still very young and it’s discovering itself.

FM: After discovering new works at bookstores, Brazilian writers broke free from the prejudice associated with comics for children by Maurício de Sousa and humoristic comics in newspapers. There is no longer a homogenous style. Each author has his/her own work, style. There are many narratives of daily routine, autobiographical reflections, and many experimental comics. This discovery process and linguistic experimentation is necessary before authors opt for longer narratives.

GB: There are also many literary adaptations, ordered by publishing houses because it’s a format they know how to work with and it can be adapted according to government plans. A change like this doesn’t happen from one day to the next because the production of a graphic novel is a slow process. However, new authors are trying to explore longer narratives. Authors like Rafael Coutinho with Mensur (or the already mentioned Cachalote) or Marcello Quintanilha with Tungstênio and Talco de Vidro. Recently, the amazing Angola Janga was released, a graphic novel by Marcelo D’Salete, which was the result of eleven years of research. These works, plus Daytripper, inspire new generations and I believe we’ll have new works coming out soon.

PL: Can you tell us more about your future projects?

GB: We’re working on two series with other writers, with whom we worked ten years ago. I’m making new chapters for the series The Umbrella Academy, with texts by Gerard Way, while Fábio is working on new chapters for Casanova with texts by Matt Fraction. In these works, we’re the only ones who draw and once we get a creative workout with styles different from the ones we’re used to, we’ll rest our minds a little bit, without rushing, so we can develop a new idea for an original story.

February 2018

Patrícia Lino

University of California, Santa Barbara