Fogwill was always there, intimately linked to my life. He’s still there, too: in part from the wound his absence has left in my memory, and in part because his voice, his awareness, his expression reach out to me whenever I’m going through a stack of paper, scrolling through emails or, most of all, reading his books (fiction and poetry).

But Fogwill was always there, even before I knew him, because Fogwill had helped invent Bazooka, the brand of Argentine chewing gum on whose wrapper you could read about the adventures of Joe Bazooka as well as your horoscope, which, because of its Zen-like ability to hit the nail on the head (or rather, because its ambiguous wording led me toward an unknown destiny), had disquieted me since my tenderest infancy.

I don’t know how many things I could chalk up to that publicist Enrique Fogwill, but I do know everything that I owe to Quique, to Fogwill, whom I met in 1980, when I was 21 years old. He was introduced to me by Enrique Pezzoni, who had selected Quique (as we knew him back then) as the winner of the Coca-Cola contest for Mis muertos punk [My punk dead] and who, after the fact, got more of a kick than anyone from the scandal Quique himself caused when he refused to accept the terms of the publication contract.

In 1983, Fogwill called me every day at Ediciones de la Flor to complain about the edition of Los pichiciegos: he didn’t like the cover; he thought the book was poorly distributed (which he suggested was deliberate); he claimed the publisher was cheating him. I know that none of that was true, except the bit about the cover, which really was ugly. But Ediciones de la Flor did everything it could to promote its books; it ensured that they were well distributed and displayed in bookshops windows, and it religiously paid royalties, which I was in charge of settling.

Deep down, Fogwill knew all of that, but he liked to complain because he had grasped the insignificance of the publishing market (relative to the advertising sector) and he knew that you could only ever expect a pittance from publishing. It was back then that I first heard him talk about Copi, whose work would obsess me for years. Thanks to him, I also read Osvaldo Lamborghini and Néstor Perlongher (he printed their work through the publisher he founded with the winnings from the Coca-Cola prize). And Fogwill sent me a thesis about the formation of revolutionary theory written by Roberto Jacoby (whom I also met around that time), which operated a little like a game, and which taught me almost everything that mattered about the relationship between war and revolution. I never returned that red, bound manuscript, and one day I decided to give it to Roberto, who, fortunately, decided to publish it many years later (El asalto al cielo: formación de la teoría revolucionaria de la Comuna 1871 a octubre de 1917 [The assault on heaven: formation of revolutionary theory from the 1871 Commune to October 1917]).

In 2008, Fogwill published a collection of his journalistic writing (Los libros de la guerra [The books of the war] Buenos Aires, Mansalva) that, in addition to its many other merits, reminds us how early on he presented ideas that many of us would “naturally” talk about it the nineties and later. At one point, I was going to write a prologue for that book, but Fogwill wouldn’t let me: “If you write it, we’d have to call it a Homologue,” he wrote me, with his special talent for combining inventiveness and invective.

To overcome that blow to my ego, when the book was published, I wrote: “Mr. Fogwill’s living thought experiments, his scholarly, sophisticated arguments, his trust in truth and beauty, have shaped us. I won’t say that Los libros de la guerra is one of the most important books of the year or that young people will benefit from reading it. I’ll only say that it should be required reading in school across the Nation.”

Fogwill had tried to get me to present the book in the Malba Museum, together with Quintín Antín, with whom I had been engaged in a bitter conflict regarding Vivir afuera in 1999. I declined, naturally: I would do many things for Fogwill, but I would not publicly expose myself to a debate in which I had lost all interest. Fogwill was angry at me for denying him the joy of a hysterical bloodbath in front of all the newspapers and press agents. I refused to be his Bazooka chewing gum, partially because he refused to let me be his homologue (he, in turn liked to go around repeating the entirely false claim that when Sebastián Freire, my husband, photographed him for an exhibition, he depicted him in the nude and tried to take advantage of him sexually).

*

Yes, Fogwill is part of my archive, understood not as a dusty collection of old papers, but as that which defines my own conditions of enunciation (which is almost to say, my own conditions of existence). If I have been able to say and write certain things, it is because of the way in which all of that reverberates in the different parts of my personal archive, some of which are called Fogwill, that “living thought” (living forever).

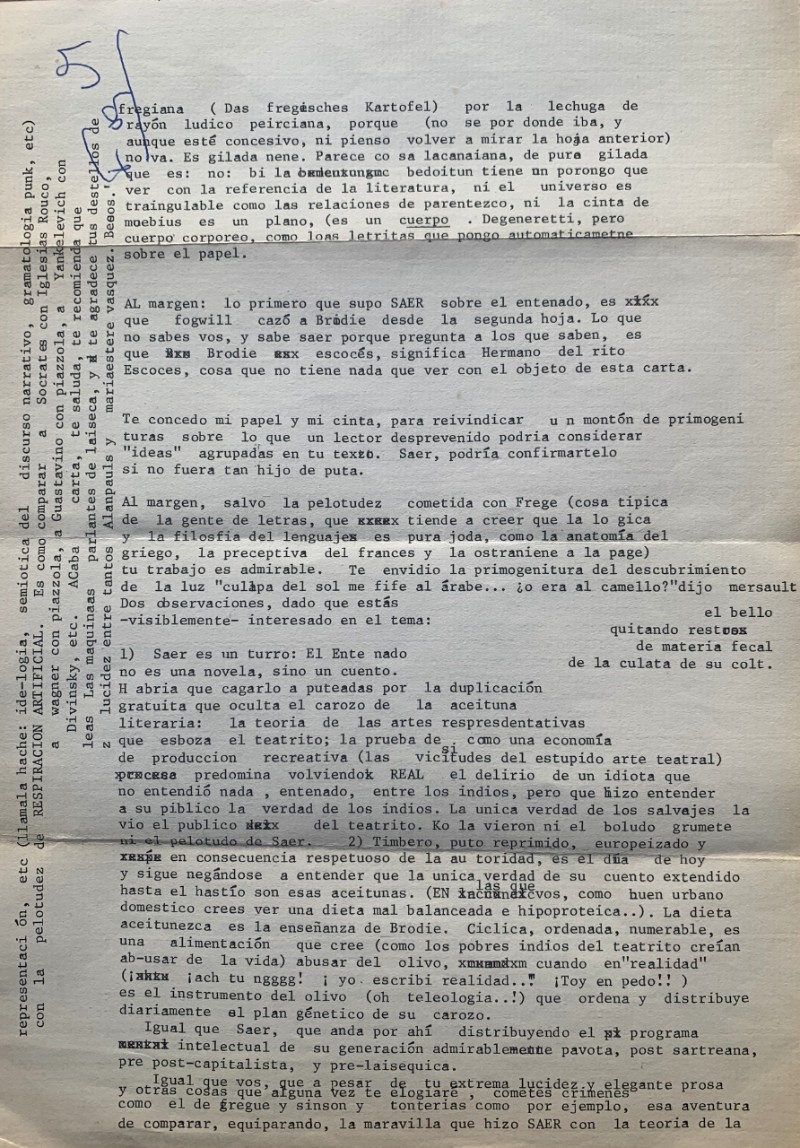

In fact, I have chosen, for this tribute, the first letter that Fogwill sent to me, on the occasion of something I wrote about El entenado (see facsimile). It’s dated March 22, 1985 (6:00 p.m.) and in it, Fogwill uses the same hand to simultaneously punch me in the jaw and pat me on the shoulder (“I concede my paper and ribbon to you, for the purpose of reclaiming all the offspring that an unguarded reader might consider ‘ideas’ collected in your text”; “your work is admirable”).

My twenty-five years’ worth of “flashes of clarity” were not enough to release me from the ignominy of trying to use the philosophy of language to read a text that was recently published, but they were enough for a literary monster (as Fogwill was back then) to write me a letter that, to me, meant at least someone was reading me.

Needless to say, at first, I wasn’t happy to receive Fogwill’s letters, because I never knew what would unleash his wrath, of which I was still terrified back then (he himself, over time, taught me to divest that terror of its power). On August 25, 1988, I received a hand-written letter on that topic. It began by describing something I never understood about parrots (I suppose in relation to a text I wrote about Luis Gusman): “I imagine that Aira, an expert in pheasants and seagulls, must know a lot about parrots.” But the important thing to me in that letter (which was addressed to “Déle,” my initials transformed into a name no one has ever called me) is his confession: “I’m ashamed of the terror I cause. So, I’ll by quiet and that’s it.” He immediately shut down the last line of my previous letter, which ended with “te quiero mucho.” He said, rightly, that loving (querer in Spanish) is easy, and that it wasn’t a question of loving; he closed his letter saying: “Te puedo mucho.”

Then comes a long, thirteen-point post-script, the last item of which says: “We have a lot left to not-talk about.”

The generalized hermeneutics that has always existed around Fogwill’s persona speaks to a kind of terror before Otherness (which he taught me to maintain not as a form of distance, but as a kind of connection), a terror before thoughts other than those that television or petite-bourgeoisie values have acclimated us to hearing (both examples being ideological apparatuses that the author abominates with equal intensity). At times, Fogwill spoke publicly against abortion and abortion-rights supporters; he declared his sympathy for the most uncouth and reactionary pope of the 20th century, he protested against tax exemptions for the arts (theatre, books, etc.). Fogwill always had something to say against common sense (especially against progressive common sense): he had decided to live outside all preconceived spaces for thought, and that is precisely what we need today in order to ensure progress for imagination, its proliferation, and its power.

Ay, Quique, ay, Fogwill, you motherfucker… I’m ashamed to think what you’d say if you saw the levels of institutional obedience we’ve reached over the years, if you saw the indecent poverty of literary writing circulating during these times without an outside. I’m outraged whenever people fail to realize that the title of Lo dado [The given], that extraordinary book of poems (Fogwill was a poet first and foremost, and among the best) is a plebeian allusion to Mallarmé. I’m revolted that they continue discussing writers’ opinions, as if that were of any interest to anyone.

In Vivir afuera [Living outside], the novel about which Quintín and I had our conflict), there is a character from another novel, Los pichiciegos (the novel I published at Ediciones de la Flor). That “character/hook” is there to thread together the different parts of that whole which is the work, and also to arrange each of Fogwill’s narrative obsessions—drugs, sex, war, surveillance systems, objects and brands, youth—his modernity, which was always, at least as an illusion, ours.

*

I am going to close for you my Fogwill archive. For me, it will always remain open, because it is part of my life and I need to remain close to that vigilant consciousness that simultaneously tells me that I wrote something well while also treating me like a dumbass for everything I wrote poorly; that simultaneously admires one of my turns of phrase while criticizing my beautician-like academicism.

I’ll close my archive with these emails we exchanged shortly before he died in 2010, which are titled “Pending Accounts,” the subject line of his original email (“settling accounts” and “giving account” were two of Quique’s obsessions).

On April 6, 2010 (9:34 p.m.), Fogwill forwarded me an email he had sent to someone else to criticize that third party’s opinions about a book (by then I had learned that Fogwill badmouthed others to me and badmouthed me to others, but this had ceased to terrify me). At the end of that forwarded email, he told the third party:

I would respond to your comment with the foulest critical arsenal.

But I will keep it to myself and I ask those who already know my opinion and this response—Daniel, Damian, and Pablo—to also keep it to themselves.

That same day (at 11:28 p.m.) I responded:

Accurate, fair, necessary.

To tell you I read your email while listening to Frauenliebe und -leben would be an abuse of your credulity and your generosity.

Best

Shortly thereafter (11:52 p.m.) Fogwill responded:

I believe you. Did you pay attention to the part about maternity?

“an meinem herzen an meinem brust,

du meine Wonne, du meine Lust”…

Doesn’t it seem like the song of a gleeful fag?

The next day (2:11 p.m.) I contradicted him:

I think you’re wrong regarding the Lieder: the song of the gleeful fag is “Du Ring an meinem Finger”… The other is the song of a woman in ecstasy…

Of course, Fogwill accepted the challenge and added (5:57 p.m.):

in terms of ecstasy, you’ll see that the musical phrase that appears in the lines of the first verse

Wie im wachen Traume

Schwebt sein Bild mir vor,

and which is repeated below the text of the second

Möchte lieber weinen,

Still im Kämmerlein

appears in altered form in

Den seligsten Tod mich schlürfen

In Tränen unendlicher Lust.

and is prefigured in R.W.’s Liebestod

and repeated in the second verse.

Fröhliche Gehören

Fogwill tried to say “happy listening,” but he used a word that can also be understood as belonging or participation. One listens from the other that in which one is participating in, or attempting to participate to. In Fogwill’s case, that is his generosity, his severity, his rigidity. And also—why not?—his inoffensive backbiting.

Translated by Kevin Gerry Dunn