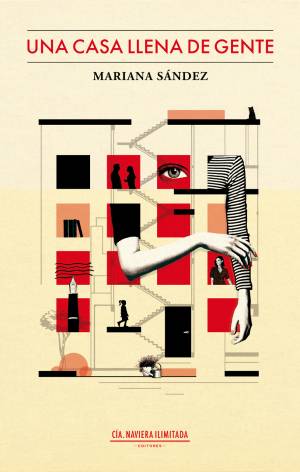

Una casa llena de gente. Mariana Sández. Buenos Aires: Compañía Naviera Ilimitada, 2019. 257 pages.

How would you react if, upon the death of your mother, you discovered that she left notebooks written specifically for you? And what would you do when you found out that what those pages contain are your mom’s intimate confessions and reflections, which may change your way of seeing a woman you thought you knew your whole life? This is the great dilemma that opens Una casa llena de gente [A house full of people], the first novel by Argentine writer Mariana Sández.

How would you react if, upon the death of your mother, you discovered that she left notebooks written specifically for you? And what would you do when you found out that what those pages contain are your mom’s intimate confessions and reflections, which may change your way of seeing a woman you thought you knew your whole life? This is the great dilemma that opens Una casa llena de gente [A house full of people], the first novel by Argentine writer Mariana Sández.

A hybrid text both in genre and structure, Una casa llena de gente doesn’t only mark the author’s debut as a novelist, but also confirms what had already been established in her short story collection Algunas familias normales [Some normal families] (2016): her ability to portray men and women in both their ordinary and absurd lives, and her talent for weaving stories in which all readers can recognize a bit of themselves.

In this case we have a mother—Leila—who, sick and aware that she doesn’t have much time left, asks her husband to give her daughter some notebooks after she dies. By leaving her this unexpected inheritance made of words, Leila hopes Charo can come to understand the turmoil of her inner world, her guilt and frustrations: everything that she won’t be able to tell her in person due to her illness, or that perhaps she’d never have the courage to say out loud. So, by accepting these notebooks, Charo obeys her mother’s last wish, and armed with this new key to understanding, sets out on a journey into the past to discover who that woman really was and what sorrows led her to her death. The novel, a marvelous portrayal of human emotions, suggests that Leila’s afflictions, which she kept quiet and hidden deep inside throughout her entire life, were what turned her blood bitter and triggered her illness. This theory appears in a novel that has much in common with Una casa llena de gente: La lección de anatomía [The anatomy lesson], in which Spanish author Marta Sanz identifies the origin of Aunt Maribel’s cancer as suffering that is psychological, and therefore invisible, yet nonetheless so oppressive as to ultimately become palpable and lethal.

In the investigation that Charo—who is only twenty-five when her mother passes away—carries out, everything points to the “castello”: the four-apartment building that the Almeida family—Charo, her parents and two stepbrothers—moved to when she was eight years old. In that building, whose thin walls seemed to invite each occupant to poke their noses in other people’s business, the Almeidas established friendly relationships with the other residents, but after a few years of idyllic coexistence, the situation deteriorated until it came to a dramatic end linked to Leila’s suffering. That’s why Charo has to delve deep into precisely the years spent in that building. Becoming a scrupulous historian, just like Natalia Ginzburg in her Léxico familiar [Family lexicon], she recalls the story of her family and the story of her neighbors, even in their most everyday actions, and puts them in writing.

But not so fast. The real “house full of people” that the title refers to is not the “castello,” but rather literature, the third protagonist of the book together with Leila and Charo. The one to suggest this charming and irrefutable definition is Leila herself, a translator but also an aspiring author and incorrigible bookworm. Here we find one of the most successful features of the novel: the portrayal, moving and humorous at the same time, of a woman who seems to painstakingly count the minutes that chores and proper social norms take away from her reading and who every day, after taking her daughter to school and dealing with housework, reaches her study “casi sin aliento […] como un isleño hambriento de carne y jabón, en su caso de lectura y soledad” [“almost breathless… like an islander hungry for meat and soap, in her case reading and solitude”]. As many critics have already noted, this uncontrollable passion seems to transform Leila into a modern-day, female version of Don Quixote. However, what’s truly interesting in my opinion is not what these two figures have in common, but rather what differentiates one from the other: while the extravagant enthusiasm of Alonso Quijano leads him to throw all caution to the wind and embark upon his feats, Leila’s veneration for literature brings about the opposite effect, and her fear of failure as a writer ends up crushing her, preventing her from realizing her dreams.

One of the greatest merits of the novel is the masterful fabric of voices recreated throughout the text. Mariana Sández doesn’t settle for reconstructing Leila’s story via an external, omniscient narrator, but rather draws from a variety of internal perspectives on the story. While this may seem like a simple matter of the author’s taste, it is actually one of the most felicitous elements of Una casa llena de gente. What the reader understands thanks to this structure is that we, like Leila, are all ultimately puzzles that cannot be reduced to a single definition, complex and fragmentary pictures that may be interpreted differently by each observer. This is why the idea of using a diverse set of materials to reconstruct the figure of Leila, putting together the fragments of her notebooks, her daughter’s narration, and bits and pieces of her daughter’s interviews with family and friends, was an ingenious one.

Speaking of minor characters, the portrayal of Leila’s mother, the fearsome Granny, is magnificent. English by birth, pragmatic and faultfinding, the old lady adds color to the narration, creating a certain comic effect with her British rigidity: “Emily Douglas, mi abuela, inglesa hasta en la forma de abrazar la almohada (como si retuviera un fragmento del Reino Unido), no permitía que nadie españolizara su nombre por el de Emilia; cuando alguien la llamaba así, le dirigía la expresión de una trituradora” [“Emily Douglas, my grandmother, English down to the way she hugged her pillow (as if it retained a fragment of the United Kingdom) didn’t let anyone Hispanicize her name and turn it into Emilia; when people called her that, she looked at them as if she were going to shred them to pieces”] Charo says, introducing her to readers.

As in all good choral novels, the style of the prose often varies, giving the narration great dynamism. Charo’s spontaneous, bright tone gives way to the more lyrical tone of her mother, but always avoiding extremes, and herein, I believe, lies the narrative strength of the book. It would have been easy to captivate the audience with moving language, but the author prefers to approach the story with an often sarcastic, humorous eye, and this allows readers to keep the distance needed in order to reflect lucidly and critically on the novel’s different themes without being carried away by sentimentalism. The pages go by quickly, but don’t be fooled: Mariana Sández’s writing is clear and fluid, while still careful; she avoids solemn tones, though there are sharp and brilliant observations that surprise the reader with their insightfulness throughout the narration.

In sum, Una casa llena de gente is a marvelous fresco of the mother-daughter relationship, a tribute to literature, and a polyphonic novel not without suspense and mysteries. The second printing, about to be released, only confirms the talent of one of the new voices of Argentine narrative.

Arianna Tognelli

Rome

Translated by Lena Greenberg

Arianna Tognelli is a graduate of the University of Bologna with a degree in Modern, Comparative, and Postcolonial Literature.

Lena Greenberg is a Translation and Interpretation MA student at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. She holds a bachelor’s degree in linguistics from the University of Pennsylvania.