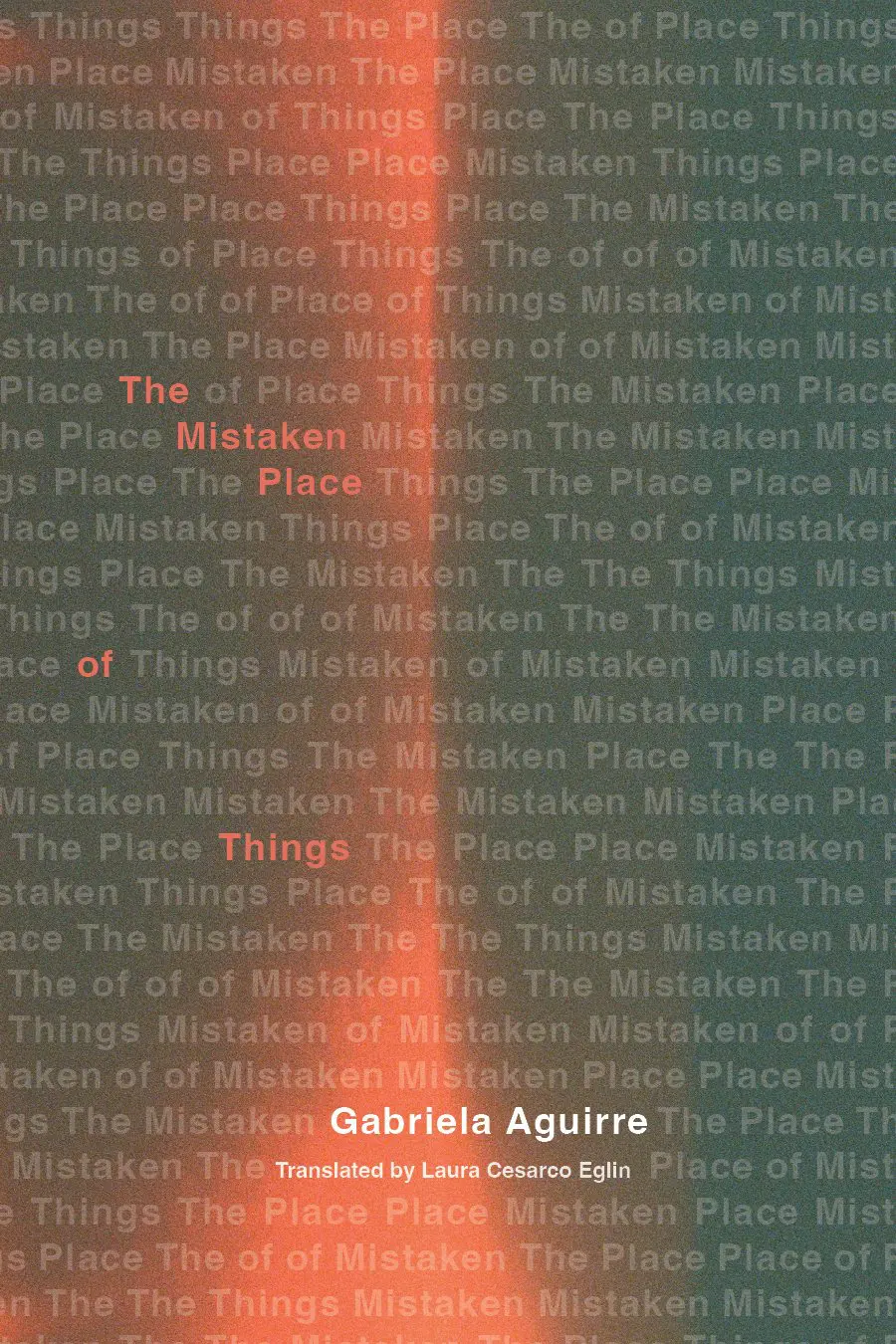

Pennsylvania: Eulalia Books, 2024. 513 pages.

I read many splendid poetry collections in 2024. Still, one that I return to is Laura Cesarco Eglin’s English translation of Mexican poet Gabriela Aguirre’s The Mistaken Place of Things. The book opens seven different windows, each with a tantalizing view allowing the reader to observe and watch the poet explore what it means to have a body. Translator Olivia Lott calls Aguirre’s work a “poetics of estrangement, where the body is ‘the only staircase available.’” We ascend and descend, taking our time with each step, with each word, with each phrase, as they turn and bend simultaneously with precision and dreaminess.

I read many splendid poetry collections in 2024. Still, one that I return to is Laura Cesarco Eglin’s English translation of Mexican poet Gabriela Aguirre’s The Mistaken Place of Things. The book opens seven different windows, each with a tantalizing view allowing the reader to observe and watch the poet explore what it means to have a body. Translator Olivia Lott calls Aguirre’s work a “poetics of estrangement, where the body is ‘the only staircase available.’” We ascend and descend, taking our time with each step, with each word, with each phrase, as they turn and bend simultaneously with precision and dreaminess.

We start in the Samalyuca Desert, a place almost mythical in its beauty and vastness located in Northern Mexico, and a reference to a text from Peruvian poet Jaime Urco: “I just wanted to write a poem / about our trip // about a hat / about the 104 degrees of friendship.” Aguirre’s lines travel corporeal and imagined landscapes, but remain aware of the poet’s spatial existence: “I just want a bit of an audience / a microphone at the right volume.” And we are a captive one, following the poets as they guide us through presence and absence—traversing the delicate relationship between Spanish and English. Aguirre writes “Si este cuerpo / es lo único que tengo // la única escalera / disponible.” Cesarco Eglin’s translations listen to the beats of Aguirre’s rhythms and lyricism and create their own pulse, allowing us a unique doorway into the poems.

“We discover metaphors through the lens of material objects: photographs, dolls, oregano, and, of course, the body.”

In the translator’s note, Laura Cesarco Eglin says The Mistaken Place of Things is “in different scenarios—the desert, photographs, the body, a hospital, dreams, questions, silence—Aguirre delves into the human experience.” As readers, we observe alternate universes, mistakes, and, above all, place, searching through a human existence. The presence of place situates itself throughout the poems, and while memory and dreams weave themselves throughout the book, there is never nostalgia or sentimentality in the poems. Instead, there are stark reminders of the very real violence that exists for bodies and the anguish of exile. The geopolitics of Mexico are never directly named, and yet we are pierced by their ferocity twice—first through Aguirre’s language and then through Cesarco Eglin’s translation. These are not prayers or supplications, but rather another dimension of interpretation. “Poetry couldn’t save you, my friend: / the birds gouged out your eyes / before you could even look at me.”

We discover metaphors through the lens of material objects: photographs, dolls, oregano, and, of course, the body. Limbs are scattered throughout the text, in haunting positions that echo the temporality of our lives, and Aguirre’s lean lines unsettle the simplicity in which they are stated. She ends on a final question that leaves the audience with a tiny cut that continues to bleed: “The heart probably / lives a little in the feet / and screams, in the dead skin, that you left. / What will you take after taking these legs?”