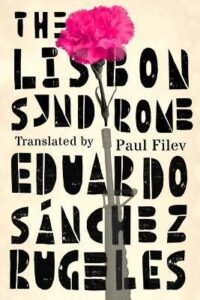

New York: Turtle Point Press. 2022. 184 pages.

The Lisbon Syndrome, by Venezuelan author Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles and translated by Paul Filev, is a novel about cataclysms. Lisbon has been hit by a meteorite and has disappeared. Rumors say this might generate a major disaster and possibly obliterate the entire planet. At the same time, on the other side of the ocean, Venezuela’s sociopolitical stability has imploded under an authoritarian regime. At a more intimate scale, in Caracas, a high school professor goes through a romantic breakup, a Portuguese migrant remembers his past and his love in his vanished country, and a group of young students is fiercely determined to fight against the dictatorship in place, some of them facing death. Everything seems to be lost, the apocalypse seems to be present in each of these stories. It is not by accident that the sun can barely be seen in the sky, completely gray due to ash rain.

The Lisbon Syndrome, by Venezuelan author Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles and translated by Paul Filev, is a novel about cataclysms. Lisbon has been hit by a meteorite and has disappeared. Rumors say this might generate a major disaster and possibly obliterate the entire planet. At the same time, on the other side of the ocean, Venezuela’s sociopolitical stability has imploded under an authoritarian regime. At a more intimate scale, in Caracas, a high school professor goes through a romantic breakup, a Portuguese migrant remembers his past and his love in his vanished country, and a group of young students is fiercely determined to fight against the dictatorship in place, some of them facing death. Everything seems to be lost, the apocalypse seems to be present in each of these stories. It is not by accident that the sun can barely be seen in the sky, completely gray due to ash rain.

The novel is divided into chapters, following the parts of a musical symphony: Overture, Allegro, Scherzo, Adagio, Requiem, and Offertory. In each movement or segment, the reader goes back and forth between the ripple effect of what happened in Lisbon, the turmoiled present in Venezuela, and the story of Fernando, the teacher; Moreira, the immigrant; and the students at risk. Fernando is a schoolteacher who works in different schools in Caracas, and also at a cultural center called La Sibila, where he imparts drama classes, becoming a guide and role model for his students, who, in distress due to the political and social debacle, take part in the city’s riots, risking their freedom and possibly their life. They see themselves as a generation suffering from “The Lisbon Syndrome”: they feel that the things they love are finite, that there is no tomorrow, that they will disappear and their disappearance will be irrelevant to the rest of the world. On the other hand, Fernando feels also that his life has lost meaning. His wife has recently left him for another man, and his mind wanders in a suspended past, obsessed with what happened, trying to understand when and how his wife stopped loving him.

In the meantime, as one might expect, censorship pervades at all levels, and no one knows with certainty what the consequences of the damage in Portugal will be. Will Europe disappear? Is this in fact the apocalypse? The story of Moreira, the Portuguese immigrant living in Caracas who turns out to be a storyteller himself and recounts his past and experiences as a foreigner while lamenting the loss of his birthplace to the meteor strike, becomes the moving belt on which the tragedy evolves. The distant reference point of an obliterated Lisbon goes hand in hand with Venezuela’s civil unrest, censorship, conspiracy theories, food shortages, and political repression.

Dedicated to the fallen, to the young Venezuelans who died defending their country from the dictatorship still in power, The Lisbon Syndrome uses the notion of the apocalypse as a very explicit symbol. Because if each human being is a universe, the world has ended once and again with each death. Planet Earth continues existing, and as we discover in the novel, the apocalypse never happens. But the universes obliterated by the Venezuelan dictatorship cannot come back to life. The Lisbon Syndrome describes a cataclysm as a metaphor for a sociopolitical debacle which is still in place. Nevertheless, Fernando’s commitment to his students, his devotion to his work, and the way he makes every effort to protect them transform the bleak perspective: they shift the story’s meaning. An apparently pessimistic view, turns into a narration about the love for freedom and the ability to walk over ruins in order to protect it, to regain it, to own it. As Moreira tells Fernando: “despite the deception and the disappointment, the essence of the things we love still remains intact. You have a firm basis for hope, even if it seems that everything is lost.”