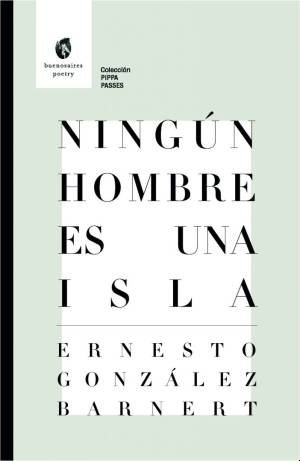

Ningún hombre es una isla. Ernesto González Barnert. Buenos Aires: Buenos Aires Poetry. 2019. 82 pages.

With Ningún hombre es una isla [No Man Is An Island], Buenos Aires Poetry press presents us a well deserved anthology of Chilean poet Ernesto González Barnert, winner of the Pablo Neruda Prize of Young Poetry in 2018. Although the book collects poems from various works, it is a coherent, unitary, and well thought-out volume. From a structural point of view, we can divide the book into four sections according to the origin of the verses: from Trabajos de luz sobre el agua (pages 9-24), from Coto de Caza (25-44), from Playlist (45-67), and from Cul de sac (68-78). The diverse origins of the poems define certain thematic differences, although we can also trace some common concerns and interests throughout the volume.

With Ningún hombre es una isla [No Man Is An Island], Buenos Aires Poetry press presents us a well deserved anthology of Chilean poet Ernesto González Barnert, winner of the Pablo Neruda Prize of Young Poetry in 2018. Although the book collects poems from various works, it is a coherent, unitary, and well thought-out volume. From a structural point of view, we can divide the book into four sections according to the origin of the verses: from Trabajos de luz sobre el agua (pages 9-24), from Coto de Caza (25-44), from Playlist (45-67), and from Cul de sac (68-78). The diverse origins of the poems define certain thematic differences, although we can also trace some common concerns and interests throughout the volume.

The work is made up of short poems, which extend from one line to two pages. Moreover, there are a couple of prose poems. All the pieces are characterized by a colloquial, almost conversational, easy, and sparkling language in free verse. Often, they consist of small recreations of scenes and daily situations at home, the apartment, the streets, public transport, or at the bar, in conversations or meetings between two people. They are sparks of sense sighted by the poet, who expresses them out of an elusive and uncertain need.

One key to a comprehensive understanding of the verse collection seems to be a metapoetic discourse about writing itself, although this subject is more present in the first section. Thus, the poem that opens the volume can be understood as a statement of the art that will be exposed throughout the work. The speaker tells us that his grandmother, in order to speak properly, used to put a stone in her mouth and read aloud, and how she forced him to do so as well. The second poem manifests the modest ambition of the poet, which is satisfied with a minor work, because, as he says, the ordinary citizen can learn little from poetry. However, the third poem positively assesses what this expression does offer: namely, the intense life of a subject.

Next come some poems that reflect on what the word does. The hard and tired gaze of the poet will continue to fight against injustice, for he feels the tragedy of immigrants, adults, and children. Likewise, the speaker doubts the truthfulness of journalism and the authorities. And although love is better expressed by silence, the poet will crown that silence with his sign.

A key image in the volume, albeit intermittent, is water, which appears in the form of rain, in the port, or as a paradoxical snow.

The erotic theme, the relationship or the reverie with various female figures, also plays a prominent role in González Barnert’s poetry. Some poems of erotic tone exhibit a speaker who addresses another person, with memories of everyday matters, intense moments of a expectant erotism, of the erotic contemplation of the beloved, of insinuations. The gaze of the poet focuses on the cherished objects that lead him to remember the beloved, whom is admired and absolutized. Women’s clothing, especially lower garments (breeches, socks, pantyhose, skirts, pants…) draw the speaker’s attention. In some pieces, other feminine presences stand out, such as those of some teenagers and schoolgirls spotted on public transport or on the streets, or maternal figures. In the poem “SÉ QUE HAY COSAS QUE NO ME CIERRAN DEL TODO” [I know that there are things that do not conclude completely], one of the most outstanding in the volume, three women (an unknown fifteen-year-old girl in the bus, an absent lover, and the speaker’s mother) merge in a fragmented enumeration, somehow gathering together all the female presences of the speaker.

As I have pointed out, the voice of the common and ordinary is expressed in the verses of the poet. We encounter the presence of everyday objects from a child’s world, school, sports, pop culture, and clothing. There are also various images of observation and description of everyday scenes such as drinking a beer on a balcony or helping the beloved to dress up. The quotidian increasingly permeates the speaker’s language through the colloquial register: “en un momento x” [at time X], “petiso” [shorty], “mameluco” [onesie]… And with Chilean idioms: “talla” for joke, “sapo” for snitch, “pingüinos” for schoolboys/girls.

Several poems that make up the second section seem to question the poet and his work. In “FIAT,” he feels the craft of writing as a necessity, but he isn’t sure of its usefulness or its purpose. This corresponds to that existential feeling of his life as “an immense frozen lake / in which I don’t know / if I’m up or down” [un inmenso lago congelado / en el que no sé / si estoy arriba o abajo]. But he immediately recognizes that “writing is that force that gets you on your knees” [escribir es esa fuerza que te pone de rodillas]; that is, poetry continues to spring out of an existential drive, a vital need. Perhaps hesitations come from the fact that, as he says, writing poetry is a kind of difficult purification.

In general, the poems of the volume don’t convey a hopeful view about communication or the possibility of building community: “Maybe everything is to fit in, to wrap up / in what our dead leave behind / and to turn off the light” [quizá todo sea calzar, arroparse / con lo que dejan nuestros muertos / y apagar la luz]. Yet, some stability comes from the speaker’s most frequently mentioned relationship, namely, the one with his brother. Or perhaps the realm of imagination is the only enduring and lasting one: “because we are ghosts / that appear and disappear / between beats that submerge every moment and with greater complication / in the deepest depth” [porque somos fantasmas / que aparecen y desaparecen / entre latidos que se sumergen cada vez y con mayor complicación / en lo más profundo].

The selected pieces from Playlist are characterized, of course, by the ubiquity of music. They are fragments that manifest the transformative power of music through the mention of specific names of songs for particular circumstances. Each musical piece colors a certain experience or renders it a certain tone. Often, music is related to ways of being, episodes in bars and drinking beer; and the analogy between music and writing is also recurring.

Regarding the edition itself, it is worth noting two errata: on page 34 (“cuándo” instead of “cuando”) and 63 (“betarras” instead of “betarraga”). Besides that, the typography, design, and materiality are correct and clean.

In general terms, although sometimes the succession of images in the poems becomes fragmentary and difficult to apprehend, the work gives a good account of González Barnert’s style. We encounter an original, individual, and mature voice which, with its various recognitions, already stands up by itself on the national poetry scene. We can only hope that this poet, born in Temuco, maintains the quality of that direct, incisive, and profound language.

Clemente Cox

Universidad de los Andes (Chile)

Clemente Cox was born in 1994 in Santiago, Chile. Currently he lives in the same city, where he teaches at the Universidad de los Andes and in a local high school. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in Philosophy (2018) and in Literature (2019) at the Universidad de los Andes. He has studied in Germany (WWU Münster), in the United States (University of Notre Dame), and in Austria (International Theological Institute). His main interests are in the field of phenomenology and poetry.