Madrid: Instituto Cervantes/Diputación de Jaén. 2023. 188 pages.

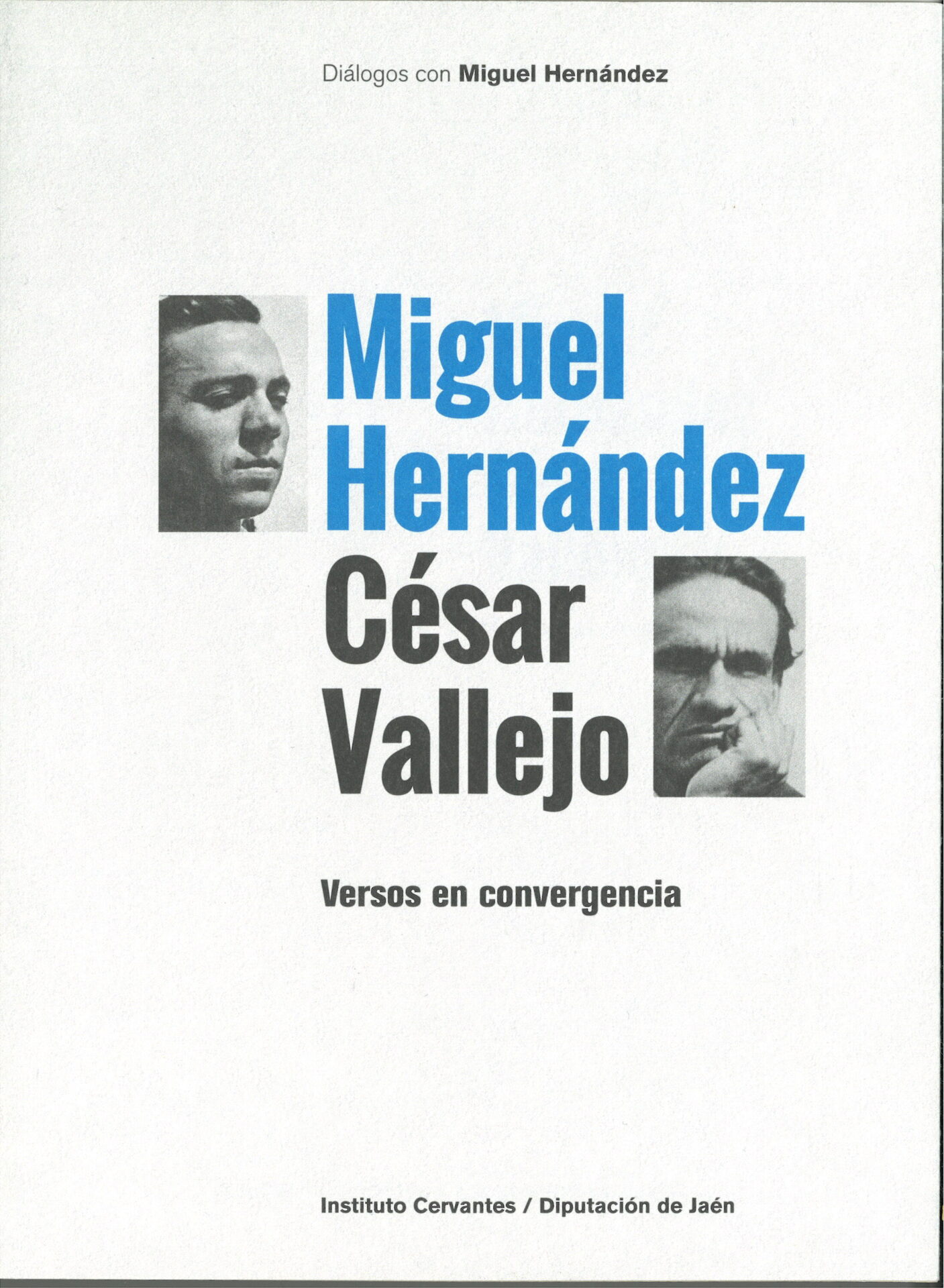

A collection of works framing Miguel Hernández in dialogue with other writers has arisen from a collaboration between the Cervantes Institute, the Provincial Government of Jaén, and the Miguel Hernández Literary Legacy Foundation of Spain. Edited by César Ferreira, Miguel Hernández y César Vallejo: Versos en convergencia is the most recent volume in this collection. It brings together two foundational poets and gives readers an opportunity to observe the connections between them, in terms of both their poetry and their lived experiences. This edition includes prologues and introductions by Luis García Montero and César Ferreira that complement one another and provide a panoramic vision of Hernández and Vallejo’s poetry, as well as their historical and political contexts.

A collection of works framing Miguel Hernández in dialogue with other writers has arisen from a collaboration between the Cervantes Institute, the Provincial Government of Jaén, and the Miguel Hernández Literary Legacy Foundation of Spain. Edited by César Ferreira, Miguel Hernández y César Vallejo: Versos en convergencia is the most recent volume in this collection. It brings together two foundational poets and gives readers an opportunity to observe the connections between them, in terms of both their poetry and their lived experiences. This edition includes prologues and introductions by Luis García Montero and César Ferreira that complement one another and provide a panoramic vision of Hernández and Vallejo’s poetry, as well as their historical and political contexts.

There are undeniable connections between Hernández and Vallejo. Both are originally from rural areas. Hernández lived out, in the flesh, the conservative and provincial reality of Orihuela in Alicante, while Vallejo had a similar experience in Santiago de Chuco, a remote town in the Peruvian Andes. Despite growing up in remote areas far from intellectual life, they both found solace in literature and a passion for literary creation. For these two authors, poetry was a way to vindicate the voice of the people. In fact, both Vallejo and Hernández conveyed strong social convictions in their poetry and daily lives. They recovered the possibility of man’s transformation, and they defended a just, united society. They dreamed of a better future.

For Vallejo, existential anguish manifests in Los heraldos negros (1919), with themes such as suffering, pain, orphanhood, and abandonment. In 1920, after an altercation in Santiago de Chuco, Vallejo was accused of having set fire to a residential building; he was detained and jailed in Trujillo from late 1920 until early 1921. Nonetheless, and despite the terrible conditions, he began writing Trilce (1922) in prison. This second book of poetry is known for experimental language and pushing the limits of the word. Vallejo was aware of the changes that the second decade of the twentieth century would bring, and for that reason, he employed a novel poetic language. In tandem, the market crash on Wall Street in 1929 eroded trust in capitalism and reinforced preferences for Marxism. Thus, it is not surprising that poets in this period adopted Marxist principles.

“We once again find proof that for Vallejo the only way to overcome pain and death was to forge a society based on solidarity, fraternity, and hope”

In 1923, Vallejo left Peru and moved to France. His interest in Marxism grew, as did his commitment to revolutionary ideals. Between 1928 and 1929, Vallejo traveled through the Soviet Union, sharing his observations in the book Rusia en 1931: Reflexiones al pie del Kremlin (1931). His political militancy led to problems in his personal life, but he nonetheless was able to make a home for himself in Paris with his partner Georgette. The start of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 consolidated Vallejo’s revolutionary commitment; through his work as a journalist, he witnessed the conflict in Spain. The following year, César Vallejo attended the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, where he met Miguel Hernández. In 1938, Vallejo suffered health problems and died in Paris. His widow, Georgette, worked on posthumous editions of Poemas humanos and España, aparta de mí este cáliz. In these last two collections of poetry, both published in Paris in 1939, we once again find proof that for Vallejo the only way to overcome pain and death was to forge a society based on solidarity, fraternity, and hope.

Miguel Hernández’s childhood was shaped primarily by his Catholicism and the rural setting where he lived. In fact, the demands of working in the fields prevented Hernández from going to high school. For Hernández, the countryside and nature were essential, not only in his personal life, but also in the first poems he wrote. Perito en lunas (1933) was Hernández’s first book of poetry and, although it had a very limited print run, it was an important and promising first step. It’s worth noting that both Vallejo and Hernández came from humble origins and their first books resulted in few copies, but thanks to the originality of their poetic voices, they gained the admiration of their readers. In 1934, Hernández went to Madrid where he wrote for magazines and other publications. After meeting Pablo Neruda, Hernández connected with the poets of the Generation of 1927 and made great friends, such as Vicente Aleixandre.

Although his Catholic beliefs and fascination with the mysteries of the natural world coexisted in his early work, eventually religion took a back seat, and his leftist ideology came to the fore. With El rayo que no cesa (1936), Hernández became one of the most important poetic voices in Spain. In this poetry collection, the domain of different poetic expressions is evident, as is a perspective in which man’s passion and tragic stance intertwine. Other recurrent themes in this work are love and complex interpersonal relationships. El rayo que no cesa includes “Elegía,” an unforgettable, extraordinary poem about the untimely death of Ramón Sijé, one of Hernández’s closest friends.

With the start of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Hernández volunteered with the People’s Militias. He supported the republican militia members in his daily life and in his poetry, and he continually documented the pain and destruction of the war. In 1937, after meeting Vallejo, Hernández traveled to Russia and wrote about his experiences. This voyage to the Soviet Union was another point of commonality for the two poets, as was their shared experience in prison. In 1939, after General Francisco Franco came to power, Hernández was arrested for crossing the border into Portugal and ended up in prison. Having been imprisoned in Huelva, Madrid, Palencia, and Toledo, Hernández’s health greatly deteriorated, and he finally died of tuberculosis in 1942. His widow, Josefina Manresa, worked on the posthumous publication of Cancionero y romancero de ausencias. Hernández and Vallejo oscillated between pain and hope, where pain was an input for poetry and a catalyst for change. Until the end of their lives, both shared the dream of a more united and just world.

Miguel Hernández y César Vallejo: Versos en convergencia offers a careful selection of poems that span each author’s most important periods and titles. Thanks to this edition, readers can learn how their poetic projects developed over decades. Similarly, the introduction provides the necessary context for clearly understanding each poet’s literary motivations, as well as the real consequences of their unrelenting social commitment. Finally, the introduction analyzes each author’s most notable poems. Therefore, thanks to this book’s many contributions, anyone, from the strictest academic to the most novice reader, can not only read these texts, but also appreciate the richness of their contexts.

Translated by Amy Olen

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee