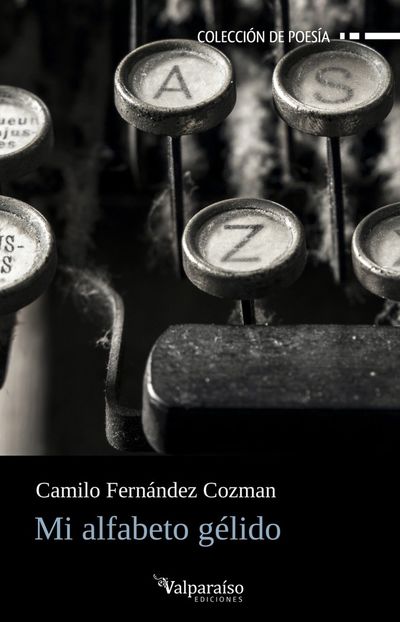

Granada: Valparaíso Ediciones. 2022. 50 pages.

Among some of its features, human verbal language behaves as a vehicle that allows us to probe and question its own limits, and also works as a tool that gets inside us to explore our subjectivity. Such are the characteristics of Mi alfabeto gélido, Camilo Fernández Cozman’s second collection of poems published twenty-eight years after Ritual del silencio (1995) saw the light. Likewise, it is worth noting that the verbal language we point out is fictionalized or literaturized, that is to say, intervened in by the author’s aesthetic awareness, but stressing that the aesthetic does not only refer to the notions of order, harmony, or other similar concepts, but also to the broad spectrum of feeling. We will focus below on three aspects of the book that are merely routes proposed to us.

Among some of its features, human verbal language behaves as a vehicle that allows us to probe and question its own limits, and also works as a tool that gets inside us to explore our subjectivity. Such are the characteristics of Mi alfabeto gélido, Camilo Fernández Cozman’s second collection of poems published twenty-eight years after Ritual del silencio (1995) saw the light. Likewise, it is worth noting that the verbal language we point out is fictionalized or literaturized, that is to say, intervened in by the author’s aesthetic awareness, but stressing that the aesthetic does not only refer to the notions of order, harmony, or other similar concepts, but also to the broad spectrum of feeling. We will focus below on three aspects of the book that are merely routes proposed to us.

An initial consideration is the incessant reflection on language and the conditions offered by the poem’s voice. Thus, in this series of texts we are faced with a speaker who almost always withdraws into the first person, a fact that leads to an inquiry on the subject of language, while establishing a connection with space and, above all, with the body. All of the above is relevant not only because it evinces the limitations of words—whose representation emerges as a synecdoche (part-whole) of the linguistic-normative system that governs us—but also because the speaker’s own body is affected by language, which results in a sort of transfer between verbal and corporal materialities. On the one hand we notice a metapoetic vein and, on the other, a word that is embodied in a labile and porous body.

For example, in terms of the strictly linguistic, the metapoetic is found in verses such as “el abecedario que me consume” [the alphabet that consumes me] or “la oración a la que llego mudo” [the prayer to which I arrive mute]; while the idea of the word that is embedded in the speaker is read in other verses such as “y yo con una coma en la garganta,” “la coma que sabe a sombra” [and me with a comma in my throat, the comma that tastes like a shadow] and also in the question “¿O jugar con las hojas secas, / con las palabras insondables / que me asfixian?” [Or play with the dry leaves, / with the unfathomable words / that suffocate me?]. In both groups, the speaker engages in an endless struggle with language to express what he thinks and feels, although at times this tension is aligned more to the coordinates of the rational that blocks the latency of an affectivity—from our perspective. Some of the poems that focus on these ideas are “Mutismo,” “Consonantes,” “Triturando sueños,” “Ejercicio de ortografía,” and “Arte poética.”

The publication of Mi alfabeto gélido showcases a voice that expands its initial creative project to other angles such as metapoetics, paternity, and the condition of the human being…

The second aspect we are interested in pointing out is the relevance of the family (with emphasis on the character of the son) for a poetic “I” who presents himself as a poet or, failing that, as a verbal creator. Furthermore, we assert that the author’s aesthetic awareness engages in an interesting conversation with the Peruvian poetic tradition; such is the case of the connection perceived between “Dinosaurio,” from this collection of poems, and “Toy” by Blanca Varela, since both texts—each one from the viewpoint of the father and the mother, respectively—revolve around the contemplation of the son’s ludic performance, which is presented as a sort of poetic starting point. The subject of the father-son relationship is complemented by other poems that express the dialectic, often frictional, between two generations (“Los bordes de un racimo”), the innocence of the son in the face of the ferocity of the world (“Luciano”), or the complexity and anguish before the continuity of life that the son implies (“Quisiera”). In all of them, the affective flow pulses in the words and briefly dilutes rationality.

Finally, we highlight the introspective breath that is given through a kind of probing of the human being’s own condition that, sometimes, is projected in the routine, in the loneliness and in the absence (perhaps) of the loved one. Thus, the references to words such as “specter,” “monster,” “ghost,” “puppets,” “esperpentos,” or “caricatures” do nothing but bring out the gray and murky situation in which the speaker finds himself, a speaker who, according to this series of poems—including “Sombra,” “Célula,” “Espectro,” “Desliz,” and “Elegía”—constantly tries to reach a point that helps him find himself, to define himself and know who he is. Therefore, the presence of loneliness (no friends, no mother, no love) becomes a space of solitary and dysphoric lucubration, and an interesting search for the face: “me pongo las sandalias / y busco mi rostro” [I put on my sandals / and look for my face] or “Yazgo sin rostro” [I lie without a face].

In short, the publication of Mi alfabeto gélido showcases a voice that expands its initial creative project to other angles such as metapoetics, paternity, and the condition of the human being under certain circumstances. Even the title itself anticipates the cold, gloomy, and still situation that the poems convey; that is to say, a personal sequence of static words that, paradoxically, serve for creation. However, even though it would have been interesting to find a little more risk in the author’s aesthetic awareness, we recover the affective aspect that seeps into some poems, which allows us to notice a much more fluid writing. Finally, the repeated search often leads to more questions and causes the speaker to plunge himself into situations that surpass him; and it is perhaps for this reason that his voice interpellates with the following lines: “somos eres / un puñado de silencio” [we are you are / a handful of silence]. It is in such silence, then, that the speaker examines his deepest dimensions and maybe his condition of “humanity.”

Translated by Luis Arista