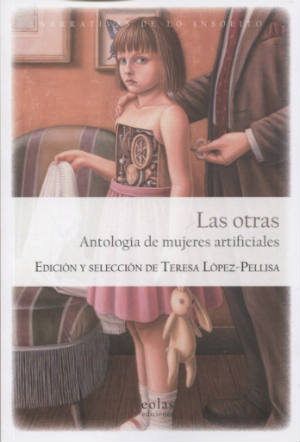

Las otras. Antología de mujeres artificiales. Edited and selected by Teresa López Pellisa. Leon, Spain: EOLAS, 2018.

There is a trend in recent Latin American and Spanish fiction towards the fantastic, science fiction, the weird, and the unusual. Teresa López Pellisa, an expert scholar of Hispanic science fiction, has put together an anthology around an original idea: take the image of womanhood—long considered “the other” by society and culture—and extrapolate it to create a collection of stories about artificial women: “The others are the ones who are not us, and in this anthology the others are artificial women created via silence, plastic, binary digits, biotechnology, surgery or other ordinary and extraordinary means,” says López Pellisa in her introduction (7).

There is a trend in recent Latin American and Spanish fiction towards the fantastic, science fiction, the weird, and the unusual. Teresa López Pellisa, an expert scholar of Hispanic science fiction, has put together an anthology around an original idea: take the image of womanhood—long considered “the other” by society and culture—and extrapolate it to create a collection of stories about artificial women: “The others are the ones who are not us, and in this anthology the others are artificial women created via silence, plastic, binary digits, biotechnology, surgery or other ordinary and extraordinary means,” says López Pellisa in her introduction (7).

There is a dual purpose to the book: to be as inclusive as possible in generational and geographical terms, and to gather authors who prefer what we might call—for lack of a better term, as Julio Cortázar would say—fantastic fiction. We find well-known Spanish writers such as José María Merino and Elia Barceló together with representatives of more recent literary promotions such as Patricia Esteban Erlés and David Roas; Mexican writers associated to the fantastic and sci-fi such as Naief Yehya, Alberto Chimal, and Guillermo Samperio (sadly deceased); canonic Argentine women writers of the fantastic like Angélica Gorodischer and Ana María Shua; and names commonly associated with science fiction like the Chilean writer Jorge Baradit and Cuban writer Yoss, among others. The characters’ double artificial nature—that is, their essence as fictional creations and, within that framework, their artificial nature— is interesting to say the least. López Pellisa refers to the myth of Galatea and the myth of Pandora to establish both canonic traditions and deviations in the literary representation of the artificial woman. Thus, she classifies the texts included in the anthology according to “types”: virtual women, biotechnological women and robotic women and dolls.

The first section includes five stories which work with several science fiction motifs: the “uploading” of a human consciousness as a road to immortality, in this case based on a romantic triangle (“Nina cambia” [Nina changes] by Chimal) or a sex change narrated by a software program (“Querub” [Cherub] by Spaniard Mar Gómez Glez). The remaining stories deal with eroticism in different ways (“Cambio de sentido” [Change of direction] by Spaniard Pablo Martín Sánchez, “Irisol” by Chilean Alicia Feniux, and “Sexbot” by Cuban Raúl Aguiar). The first two are not memorable, but the third one displays a narrative force through a laconic style that combines the Cuban context and science fiction, even though once again women are represented as prostitutes.

Eight stories complete the second section and all of them reveal a common thread: the emphasis on the body, specifically the female body. Chilean Lina Meruane revisits the idea of the body linked to mutilation and sickness (“Doble de cuerpo” [Body double]). At times, the abundance of technical terms—one of the worst traits of less successful science fiction—disturbs the reading experience; this is the case for example of “El eterno femenino” [The eternal feminine] by Argentine Sergio Gaut Vel Hartman: “they died in the second globus attack with pikas. Pikas were spores…” (93; my translation). Plots against the system with a strong female presence take center stage in “Hijas de Lilith” [Daughters of Lilith], a long and expertly written story by Barceló, and the role of corporations and technology drive “La oda de Dios” [The ode of God] by Costa Rican Iván Molina Jiménez and “Cyber-proletaria” [Cyber-proletarian] by Peruvian Claudia Salazar Jiménez. The beginnings of the stories by Bolivian Edmundo Paz Soldán (“When mom was declared artificial it rained all day”, 133; my translation) and by Yoss (“Now that acid rain erased all faces you look at me and tell me I’m crazy”, 141; my translation) show their knack for the mechanisms of a good short story. “La estrella de la mañana” [The morning star] by Baradit probes a futuristic religion in a post-apocalyptic Santiago. Of the three stories that round up the section (“Sed” [Thirst] by Spanish Ricard Ruiz Garzón; “Mujer por elección” [Woman by choice] by Chilean Diego Muñoz Valenzuela and “La pregunta de todos los días” [The everyday question] by Spaniard Sofía Rhei), this last one is the most original: a woman android, Loola, assimilates all of “universal literature” (167; my translation) and discovers a strange colony of rebel “literary” beings.

The last section, with ten stories, is the most diverse. Merino, Gorodischer, Shua—the best-known authors included here—do not innovate: Shua provides lyric microfiction; Gorodischer, her conversational style and Merino is average. Corporations reappear in “Kitzka 2.1” by Yehya, “Deirdre” by Spaniard Lola Robles, and in “Hijos perfectos para sistemas imperfectos” [Perfect children for imperfect systems] by Spaniard Gerard Giux, where the main character is a female android who works in a fertility clinic. The creation by a man of an artificial woman or “perfect” wife is at the heart of “Sybil” by Samperio and “Sad End” by Erlés. And the stories that close the book—“La trampa y la presa” [The trap and the prisoner] by Spaniard Juan Jacinto Muñoz Rengel, and “Casa con muñecas” [House with dolls] by Spaniard Roas—come back to well-known topics of the fantastic and science fiction genres: the obsession with a female artificial being and (living?) dolls who watch over us. Roas frequently combines the fantastic and uncanny with the absurd and the results are usually refreshing.

The fantastic, the strange, and science fiction are potentially destabilizing forces and, perhaps because of this reason, are deemed “popular” or seen as “escapist”. It is true that at times books like Las otras. Antología de mujeres artificiales [The others: anthology of artificial women] have more of an interest in substance over style—that is, they want to tell rather than show through working with language or thinking about literature—but this anthology expertly put together by López Pellisa is, in many ways, a sign of the times. It is commendable that EOLAS has created this collection of “The Doors of the Possible”. #MeToo, the return of fascism, climate change, gender fluidity, the future of our bodies and our humanity, the function of art—these are themes that concern us all. What better way to ask about them that by reading stories like the ones found in this book?

Pablo Brescia

University of South Florida

Pablo Brescia is professor at the University of South Florida (Tampa), where he teaches courses on 20th and 21st century Latin American literature, culture and film. He is the author of Borges. Cinco especulaciones [Borges: five speculations] (2015) and Modelos y prácticas en el cuento hispanoamericano: Arreola, Borges, Cortázar [Models and practices in the Spanish-American short story: Arreola, Borges, Cortázar] (2011), and the editor of six other academic books on McOndo and the Crack generations, Cortázar, Mexican flash fiction, the Latin American short story sequence, Borges, and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. He has published three books of short stories: La derrota de lo real/The Defeat of the Real (USA/Mexico, 2017), Fuera de Lugar/Out of Place (Peru, 2012/Mexico, 2013) and La apariencia de las cosas/The Appearance of Things (México, 1997), and a book of hybrid texts, No hay tiempo para la poesía/No Time for Poetry (Buenos Aires, 2011), under the pen name Harry Bimer.