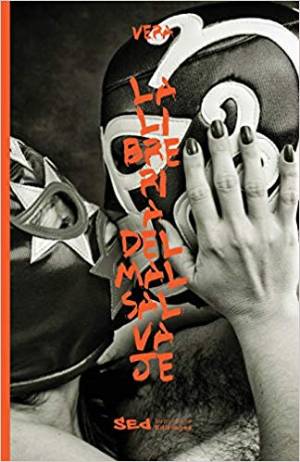

La librería del mal salvaje. Hernán Vera Álvarez. Miami: SED Ediciones, 2018. 212 pages.

Estar completamente solo rodeado de libros

es regalarse un ticket al mejor lugar.

[To be completely alone and surrounded by books

is to give yourself a ticket to the best of places.]

Hernán Vera Álvarez

Prepare yourself, whoever holds a copy of La librería del mal salvaje [The bookstore of the ignoble savage] (recipient of the Florida Book Award), to follow the footsteps of a reader, an author, and a meticulous and stubborn bookseller. The book is comprised of titled but unnumbered chapters, ranging in length from two lines to two pages, crónicas, personal reflections on reading and writing, and intersecting perspectives on the biographies of authors, alongside bibliographical citations, all of which are fragmentarily linked from start to finish without the need of a narrative order.

Prepare yourself, whoever holds a copy of La librería del mal salvaje [The bookstore of the ignoble savage] (recipient of the Florida Book Award), to follow the footsteps of a reader, an author, and a meticulous and stubborn bookseller. The book is comprised of titled but unnumbered chapters, ranging in length from two lines to two pages, crónicas, personal reflections on reading and writing, and intersecting perspectives on the biographies of authors, alongside bibliographical citations, all of which are fragmentarily linked from start to finish without the need of a narrative order.

Like the body of a dolphin that momentarily breaks the surface only to disappear again, there is a spinal column that gives continuity to the work. It’s a list (this one is, in fact, numbered) of tidbits, a smattering of obliquely related fun facts that connect disparate ideas about writing and the creative process, such as biographical episodes and other various and sundry curiosities. Within these lists, birthplaces, suicide rates, disappearances, infatuations, and divorces are favorite brands of cigarettes, names of editors, of cities, and titles of works by a diverse range of authors (the majority of which are male, it must be said) such as Cortázar, Casares, Ocampo, Lugones, Borges, and Pizarnik. In addition to a bibliographical and emotional relationship, real or imaginary, between these authors and their evolutions, the subversive inserts that appear and disappear throughout the book remarkably offer a sense of cohesion. It lifts the reader onto the back of the dolphin, allowing them to be swept away by its whimsical curves.

The first chapter, “El orden de las cosas” [The order of things], claims that a library is an autobiography and, in doing so, suggests an evolution: the gaze of a Hispanic author based in the United States is linked to the voice of a bookseller in charge of a Spanish bookstore in Miami, which is connected to the history of its customers and, of equal importance, to that of the authors and their works on sale. This autobiographical framework is constructed through the lens provided by the books chosen by the customers themselves or for them by the one who filters their voices that meticulously observes from an ironic and critical yet simultaneously sensitive and wonderful subjectivity in the presence of the literary.

From the perspective of the possibilities that the autobiographical notion offers, the first chapter ends with a quote by Thomas Mann, “Una ciudad es una obra colectiva” [A city is a collective work]. In response, the narrator says: if that’s the case, then this bookstore is as well. It’s even possible to take another step further: if a city and a bookstore are both collective works, then the book that is held in the hands of the reader must also be considered. The numerous gazes of the narrator, cronista, and stubborn reader of authorial voices, at the wanderings of the customers and the transformation of the volumes that, once paid for, will leave from there swinging in a plastic bag, ready to become a part of another autobiography, that of the library that will receive them, offer a choral work and, why not say it, in a certain way, collective.

Anchored to a momentous point in contemporary American history, La librería del mal salvaje establishes a critique of consumerism and the dominating superfluousness of the culture according to market changes or, better yet, the market according to culture changes. “Este país es un negocio. Y esta ciudad es un atraco” [This country is a business. And this city is the attraction]. Not without pessimism or desperation, the bookstore is the imagined realization of an alternative and subversive landscape illustrated by the simplest experience: “En estos tiempos oscuros trabajar en una librería que tiene especialmente obras en español es un acto estético y no menos político” [In these dark times, working in a bookstore that specializes in Spanish works is an aesthetic act and no less political] says the clerk, who knows that even his job guiding the customers through the corridors and placing them before the bookshelf or the book that best suits them is a powerful act. On the other hand, when he manages to sell a book by association that a client was not looking for, he feels bad, “un impostor, es decir un vendedor, un maldito cretino” [an imposter, that’s to say, a salesman, a damned fool.]

Now, if living surrounded by books is the clerk’s ideal, the social aspect associated with literary promotion is far from being his favorite iteration. In that way, it associates the presentation of a book with a Tupperware party. “Terminados los discursos, el público —y los oradores— se abalanzaron sobre la mesa con comida. A pocos metros yacían apiladas las obras completas que como el gran poeta regresaban al lugar de siempre: el implacable olvido” [The speeches ended, the public—and the speakers—pounced on the food table. A few meters away lie a stack of completed works that, like the great poets, returned to the usual place: implacably forgotten]. It’s an ironic desperation in the face of the evolution of the author and their work, the bookstore itself, and his own job. But La librería del mal salvaje opposes pessimism, it endures apathy: “Hola, sí, estoy buscando el Principito, de Maquiavelo” [Hello, yes, I’m looking for The Little Prince by Machiavelli].

It goes without saying that the autobiographical viewpoint is enchanting: “Me gusta ser librero. Recomendar lo que leí y los bellos libros de mis buenos amigos. Y con el mismo placer denostar a algunos escritores” [I like being a bookseller. Recommending what I read and the beautiful books of my good friends. And, with the same pleasure, insult some authors]. A light turns on: from a corner, perhaps at the end of the last launch circus for those complete works that no one will buy, the bookseller comes to the rescue. He will order chairs, place new volumes on the novelty table, and endure the client who, after asking about all sorts of books, all of which being available at the store, will give their thanks, turn tail, and never return. He’ll return to his place.

New clients bring their atmosphere and take it back with them, they enter and leave in a dance, they cry when they find the sought-after title or, once settled in, never want to leave. As is the case of “Mamushka,” who reads Proust in a corner for hours “con la distancia agradecida de quien sabe que nada en el mundo importa demasiado” [with the appreciated distance of someone who knows that nothing in this world is that important]. Only the bookseller, and whoever reads La librería del mal salvaje, is familiar with this idea of sitting beyond the clutches of time, being in one’s own place, sister to the cronista bookseller and the Russian doll absorbed in Proust. Because it is from the outside that the system that orders everything is established, that one can see better, and that one can any tale can be told.

And speaking of order, returning to the notion of the autobiography and keeping the idea of the peripheral close at hand, the reader participates in a series of extremely personal restitutions in a way that no one asked for, but that prove to be necessary. Guided by a peculiar perception of beauty or justice, it settles scores and attends to the unprotected. Two authors who became enemies in life, two longtime lovers, two lifelong friends, are suddenly reconnected by their overseer, “a los suicidas —siempre los poetas ganan en la lista— los dejo en la sección infantil” [the suicides—the poets are always at the top of the list—I leave in the children’s section]. In this reordering of the shelves, in the connection between events and authors and dates and titles of books or their translations: “Al lado del libro de Kerouac llamado En el camino, coloco otro libro de Kerouac titulado En la carretera” [Alongside Kerouac’s book titled On the Road, I have placed another book by Kerouac titled On the highway] and from a compilation of brilliantly selected, sophisticated but not scholarly vignettes, a new universe is created: that which could have been but never was.

La librería del mal salvaje is able to briefly delve into each wave or chapter, bringing the undulating back of the dolphin to the surface, or letting it be swept away by the current. It offers as many beginnings as readers, just as a bookstore with as many books as interests. If the bookseller defines literary happiness as, “Ver la alegría en el rostro de un cliente que regresa y te da las gracias por el libro que le recomendaste” [Seeing the joy on a client’s face that comes back and thanks you for the book you recommended], and if all this is nothing more than a collective autobiography, if this book is also a bookstore, then whoever picks it up should be making its author “literarily happy.”

Keila Vall de la Ville

Translated by Eric Holman

Keila Vall de la Ville is a New York based Venezuelan author. Author of the novel Los días animales (OT, 2016) shortlisted as Best Novel by International Latino Book Award 2018. Author of the short stories books Ana no duerme (Monte Avila Editores, 2007), Ana no duerme y otros cuentos (Sudaquia, 2016); and the poetry book Viaje legado (Bid&Co, 2016). Editor of the American bilingual anthology Entre el aliento y el precipicio. Poéticas sobre la belleza / Between the Breath and the Abyss. Poetics on Beauty (Amargord, in press), and co-editor of 102 Poetas en Jamming (OT, 2014). Co-founder of the movement “Jamming Poético” (2011 to present, Caracas; 2017 to present, NYC). Columnist of “Nota al Margen” for Papel literario, literature section of the Venezuelan newspaper El Nacional; and “The Flash”, for the New York Magazine Viceversa. Included in several continental and european anthologies. BA in Anthropology (Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas), MA in Political Science (Universidad Simón Bolívar, Caracas), MFA in Creative Writing (NYU, New York), and MA in Hispanic Cultural Studies (Columbia University, New York).

Eric Holman is a graduate student at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey studying Translation and Interpretation. He holds bachelor’s degrees in Spanish and International Area Studies from Saint Mary’s College of California.