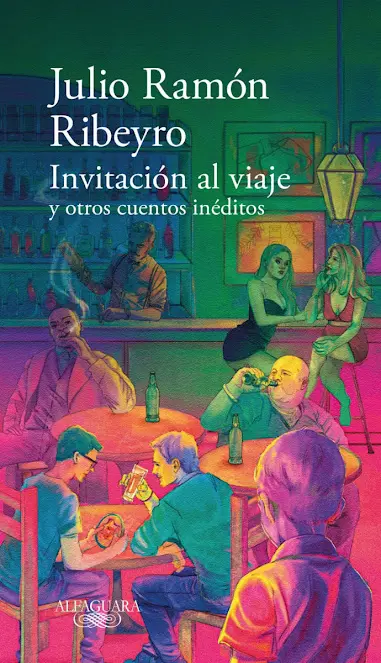

Lima: Alfaguara, 2024. 137 pages.

Julio Ramón Ribeyro (1929-1994) was one of the most versatile and talented writers of twentieth-century Peruvian literature. For four decades, he made important incursions into genres such as the novel, theater, essay, personal diary, and short prose. However, he left his most significant mark on the short story. Nearly thirty years after his death in Lima on December 4, 1994, his collection of short fiction titled La palabra del mudo remains a classic of Peruvian and Latin American letters. In his short fiction, Ribeyro crafts one of the richest portrayals of the idiosyncrasies of contemporary Peruvian society, a depiction that remains useful for understanding present-day Peru.

Julio Ramón Ribeyro (1929-1994) was one of the most versatile and talented writers of twentieth-century Peruvian literature. For four decades, he made important incursions into genres such as the novel, theater, essay, personal diary, and short prose. However, he left his most significant mark on the short story. Nearly thirty years after his death in Lima on December 4, 1994, his collection of short fiction titled La palabra del mudo remains a classic of Peruvian and Latin American letters. In his short fiction, Ribeyro crafts one of the richest portrayals of the idiosyncrasies of contemporary Peruvian society, a depiction that remains useful for understanding present-day Peru.

In February 2024, researcher Jorge Coaguila, author of Ribeyro, una vida (2021), the most accomplished biography on Ribeyro to date, had the opportunity to explore the writer’s archive at his home in Paris. Until then, the author’s papers had been carefully guarded by his widow Alida Cordero. Coaguila first met Ribeyro in the early 1990s in Lima and eventually became his personal assistant. Some three decades later, Alida Cordero, convinced by Coaguila’s dedication to Ribeyro’s work after his death, decided to give the researcher full access to the writer’s archive. Thus, by rummaging through a closet jam-packed with papers, Coaguila found manuscripts of Ribeyro’s novels, notes in his handwriting, letters and personal documents, and, more importantly, five unknown, unpublished short stories.

The five tales included in Invitación al viaje y otros cuentos inéditos were written in Paris in the 1970s, during one of Ribeyro’s most productive periods. In what turned out to be an exciting literary development in Peru, the collection was released in July 2024. It quickly became the top-selling book at the most recent International Book Fair in Lima, confirming the admiration and interest Ribeyro continues to inspire in his many readers.

In March 2024, Gabriel García Márquez’s posthumous novel Until August revived an old polemic: Should the stories an author refused to publish during his lifetime be made public? The extent of opinions on this matter reminds us that arguments for and against publication circulated about the works of other great authors, including Franz Kafka and Ernest Hemingway. With the publication of Ribeyro’s new short stories, this question arises once again.

“Despite the disparity of these pieces, Invitación al viaje y otros cuentos inéditos is yet another opportunity to read such a talented storyteller as Julio Ramón Ribeyro.”

We will never know for certain why Ribeyro refused to publish these five tales during his lifetime. And although we could argue that these stories lack the artistic merits of his other works, certain texts in the collection clearly justify their recovery. The first of these is the story for which the book is titled. The story’s protagonist is Lucho, an adolescent boy and member of the Peruvian middle class who goes to the “unknown land,” which, for him, is the working-class neighborhood of Surquillo. Lucho goes there in search of late-night adventures that will turn him into a man. In doing so, he leaves behind the security of Miraflores, his childhood neighborhood, to explore lowbrow street fairs, sleazy bars, and sordid brothels in the “darkness of night,” only to find humiliation and defeat. Two elements in this story are central to all of Ribeyro’s writing: the recreation of a disturbing urban space marked by the marginality of the characters who inhabit it, and the use of transparent and functional language that leads to sober, yet occasionally lyrical, sentences. Lucho could well be labeled just another loser—Ribeyro’s stories are full of figures who, in reality, are treated harshly—but this is not the case here. Rather, the narrator treats the protagonist with compassion and a certain generosity. Thus, the result of Lucho’s night-time excursions can be read as an important rite of passage that leaves its mark on the young man’s life.

In “Monerías,” Ribeyro’s use of humor is unfettered and boundless, which makes this story another valuable rescue. The absurdity of the plot resides in the endeavors of a Peruvian businessman, Américo Diosdado, who tries to make his fortune by exporting twelve hundred monkeys from the Peruvian jungle to the United States. So hare-brained is the protagonist’s adventure that, after failing in his attempt, he sends a letter to the President of the Republic requesting governmental help to carry out his bizarre project. At that point, however, the hundreds of monkeys Américo brought from the jungle are running loose in the streets of Lima, causing all types of damage and chaos. Nevertheless, the protagonist affirms that the monkeys “have learned our language” and “demand to be treated as the neighbors they are.” “Monerías” is a comical and enjoyable short story that confirms the place of satire and humor in Ribeyro’s vast narrative register.

Humor and a certain playfulness are also present in “La celada” and “Espíritus,” two stories that showcase Ribeyro’s command of the literary fantastic. “La celada” tells of the narrator-protagonist’s many visits to Glady’s apartment; she is a cosmopolitan resident of Lima the protagonist met in Paris and to whom he feels attracted. Strangely, depending on the door the protagonist knocks on each time he visits, the right one or left one, Gladys is either a sociable and hospitable lady or, conversely, a cold and distant individual. Although the plot of “La celada” is witty and funny, its closure is somewhat abrupt and unsettling. Something similar can be said about “Espíritus,” which tells the story of a seance involving three Peruvian friends in Paris. The narrative concludes with the sudden appearance days later of a strange “metal object” in the protagonist’s small Parisian apartment. This reminds us of “Ridder y el pisapapeles,” one of the most successful fantastic stories Ribeyro ever wrote. Like “Espíritus,” “Las laceraciones de Pierluca” is a less successful narrative in which the protagonist’s initial vitality and enthusiasm does not correspond to his unexpected death.

Despite the disparity of these pieces, Invitación al viaje y otros cuentos inéditos is yet another opportunity to read such a talented storyteller as Julio Ramón Ribeyro. Moreover, with the publication of these five new pieces, Ribeyro’s entire short story oeuvre includes one hundred published works, an important milestone that is worthy of praise and admiration.