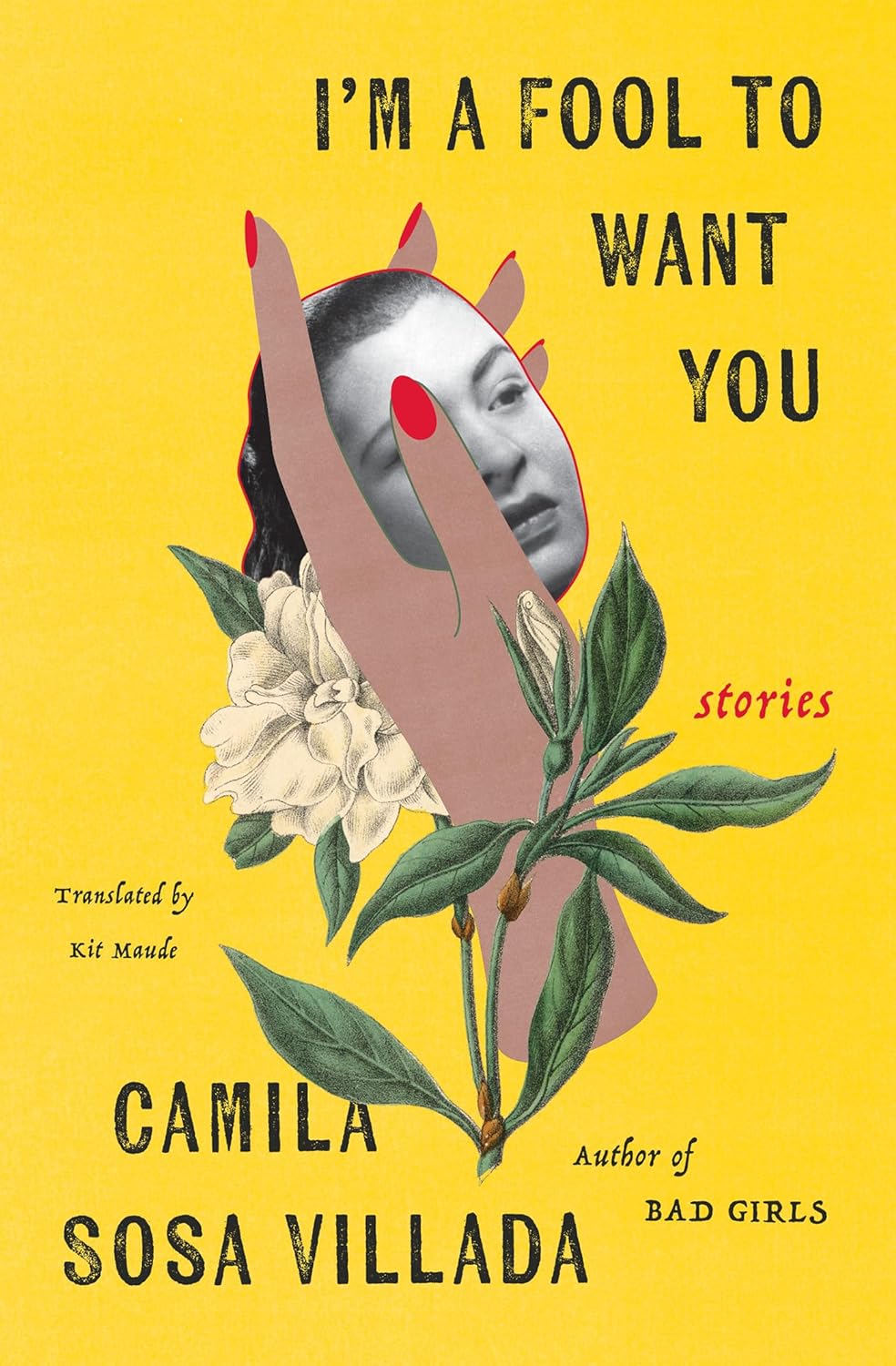

New York: Other Press. 2024. 256 pages.

As the title suggests, I’m a Fool to Want You is full of yearning, self-loathing and unrequited love. Other Press’ second collaboration with Camila Sosa Villada—following 2021’s Bad Girls—is packed to the brim with the discarded: from single fathers dragging their children up to victims of the Spanish Inquisition burning at the stake, the stories that make up this collection are sustained by a melody of persecuted voices. A mixture of autobiographical and dystopian modes, Kit Maude’s upcoming translation of these stories captures a central message of Sosa Villada’s: despite ostensible signs of progress, hatred is ingrained in humanity, and this will always hold us back.

As the title suggests, I’m a Fool to Want You is full of yearning, self-loathing and unrequited love. Other Press’ second collaboration with Camila Sosa Villada—following 2021’s Bad Girls—is packed to the brim with the discarded: from single fathers dragging their children up to victims of the Spanish Inquisition burning at the stake, the stories that make up this collection are sustained by a melody of persecuted voices. A mixture of autobiographical and dystopian modes, Kit Maude’s upcoming translation of these stories captures a central message of Sosa Villada’s: despite ostensible signs of progress, hatred is ingrained in humanity, and this will always hold us back.

Sosa Villada is herself a travesti (a Latin American term designating a born male identifying as a woman, primarily used to avoid the pathologising connotations associated with terms like drag and cross-dressing), and she often turns to her own history to provide firsthand accounts of the life of a travesti. It is almost immediately made clear that Sosa Villada is leaning heavily on autobiographical material in certain stories. Take the following line from “Thank You, Difunta Correa”: “In literature you can’t disguise a first person, the phrases start to wither three or four paragraphs in.” The story tells of her early days as a prostitute—a profession life had often shown her she “wasn’t smart enough to make it as”—and her parents’ visit to the shrine of Difunta Correa to wish for a better life for their daughter. Perhaps they saw some common ground between them: when her husband was abandoned by the Montoneros in the Argentine civil war, Correa left with her child to go in search of him. Days later, her corpse was discovered by some passing gauchos, who found her son plein de vie, drinking milk from his mother’s breast. Perhaps all Sosa Villada’s suffering was also leading up to a miracle. And while her parents initially interpret her change of fortune as divine intervention—becoming an almost overnight success in the theatre world—she takes the opportunity on stage to give them her interpretation of the miracle, as well as some formative details from her last career they would rather not have discovered.

Probably the best account of her life as a sex worker is given in “The Night Doesn’t Want to End Just Yet,” which details a typical night on the town. Opening with some tips on how best to make scones—the little luxury our narrator affords herself whenever herpersonal finances allow—the story quickly turns to her in a car full of rugby players—“the kind of handsome kids you really relish screwing over”—as they drive to their country club. They can’t pay her rate, but her rent payments are coming up, and Sosa Villada is pragmatic enough to know that “when you fail as a whore, start begging.” In a bedroom of the country club—which used to be a church—Sosa Villada describes the performance of her clients; able to detach herself from the situation, she also manages to scan the room and make observations about other members of the party. One of the girls present, for example, tells the rugby players, “You can’t actually pay this tramp,” while snorting the same dragonfly our narrator had taken earlier. And despite them all throwing insults at her when they discover she is a travesti, they hold back when she is pegging one of their own with his mother’s dildo. Despite their apparent riches, they refuse to pay her in full. Determined to write her own contract, Sosa Villada sneaks out with an expensive looking watch, pawning it the next day without any bartering, and safe in the knowledge that she won’t face any consequences: “People don’t usually complain about my thefts… I guess their reputation is worth more to them.” The story closes with a final tip about preparing scones, leaving the impression that the action at the heart of this story—harrowing enough to mark most lives—is little more than a tangent for the narrator, a night like many others that has gotten in the way of her recipe.

“In these stories, Sosa Villada seems to be showing that suffering is, for travestis, their lot in life. Jumping around in space and time, she shows quite how widespread and universal this subjugation is”

The book moves away from Sosa Villada’s own experiences in the title piece, as the streets of Buenos Aires are traded for the smoking dens of 1950s Harlem. “I’m a Fool to Want You” follows Maria—or Carlos, as they are known to the daylight hours—and Ava, two Mexican travestis who made their way to New York with dreams of becoming coiffeurs. Their wishes are quickly usurped by Billie Holiday falling into their lives, who, despite her waning stardom and various dependencies, is like an angel to them, even though they had never listened to one of her records. Like Maria and Ava, Billie is fighting the good fight: “She knew just how much… the world needed to be turned upside down.” Maria, who had been so ashamed of her manhood, who looked at her penis with the same look of disgust she detected in many a New Yorker’s face, was now arm in arm with the Billie Holiday, being paraded around by her as she proudly told passersby that this lady is her friend. Ultimately, the glittering prize of acceptance slips through Maria’s fingers, as she finds herself as a man once more. It is, seemingly, an inescapable fate, one that Maria sums up as follows: “The hatred people feel for us is a legacy of humanity.”

In these stories, Sosa Villada seems to be showing that suffering is, for travestis, their lot in life. Jumping around in space and time, she shows quite how widespread and universal this subjugation is. In the collection’s penultimate story, we jump three hundred years back in time and over to Mexico, to the final days of fourteen prisoners charged with sodomy who have been sentenced to burn at the stake. The undoing of the homosexual subculture in 1600s Mexico is narrated by Cotita de la Encarnación herself, a travesti mullato whose men-only parties were a prime example of the “hidden pleasures” the Spanish Inquisition sought to eradicate. She recognises a number of faces on the way to the stake, from Spanish soldiers—whose names, despite being given up by the prisoners, were quickly pardoned—to old friends, all of whom had previously been cognizant and accepting of her lifestyle:

Their parents knew me, they knew I was honorable, that I’d never hurt anyone or the sacred land of Mexico, the dust of the dead over which we walked or the vision of a god in his far-off heaven. The children shouted for joy. They celebrated… they spat too.

The subject of this collection’s title is, seemingly, twofold. While there are stories of unrequited love and longing here that are more universal, at times it seems that the travestis are directing the declaration inward. They see themselves as stubborn fools to embrace that side of them the world at large will never tolerate; the hatred of travestis is, after all, part of the world’s legacy.