Caracas: Editorial Eclepsidra. 2021. 102 pages.

If someone asks tell them

nothing’s going on here, it’s just life…

Eliseo Diego

Just as we cannot hold

a gaze too long,

nor can we hold

for too long on to joy…

Roberto Juarroz

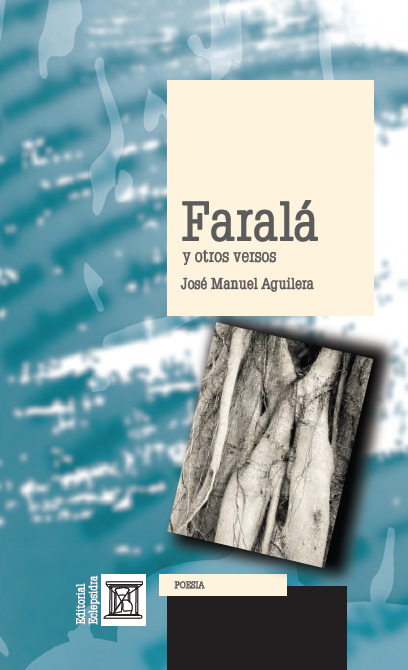

I chose these epigraphs because they light the path taken by not only the painstaking composition but also the feeling—never overflowing but always manifest—and the recollections of the narrator of Faralá y otros versos (Editorial Eclepsidra, 2021). The reader sometimes mistakes this narrator, unwittingly, for the book’s author, José Manuel Aguilera.

I chose these epigraphs because they light the path taken by not only the painstaking composition but also the feeling—never overflowing but always manifest—and the recollections of the narrator of Faralá y otros versos (Editorial Eclepsidra, 2021). The reader sometimes mistakes this narrator, unwittingly, for the book’s author, José Manuel Aguilera.

And the reader will find, in the book’s more than forty stopping places, a wakeful breath, with air and a pulse all its own. It’s like an intense, immanent exusion or a rhizome sinking to the bottom of subterranean depths in search of raw material with which to build the vital architectures that will fill this space provided by Eclepsidra. And it’s not a matter of invoking the lively and endearing, thus giving body to these pages (while this is important and obvious, at least to me). This book’s essence, rather, is life itself, with its tedium, its spleen, its saudade, its fleeting joy, its immodesty, its shaky laughter, its complaints, illnesses, tragedies, moments of happiness, its absurd bureaucratic routines; life that is leery and nostalgic, stoical and plaintive, that reaches closure or is full of uncertainty, steering with a relativist compass, all pauses and needles; life that is an everyday effort to come together, although in passing it comes apart; this whole oceanic monsoon is audible, it echoes, it reverberates colloquially, without linguistic pretense, with few metaphors, but rather with great plainness, simplicity, and naturality in Faralá y otros versos.

Another invitation from this narrator comes from certain signals, strewn here and there, that put a spontaneous smirk on our faces—one that only turns into a smile in rare cases because generally, when the book slips into irony, it only does so with wonder, strangeness, admiration, or slight humor. The book’s very title perhaps nudges us toward this territory. Faralá, the Royal Spanish Academy tells us, comes from farfalá, the ruffle or frill on certain attire, often excessive and “in poor taste.” But the poem that bears this title, on page 39, offers neither ruffles nor frills: “The epilogue in history. / The last instants of skin. // Do we know how they are? (…) The last loneliness, the kiss, the hug lost in the curtain, did it happen?” But maybe this philosophical question is ironic too. It’s worth mentioning that José Manuel is fixated on the world of appearances, and rests when that covering or surface gives way.

I was fascinated by the subtlety of this book’s structure. While it gives the impression of moving forward from beginning to end along a single course, that’s not really the case. Initially, the texts doggedly seek balance through verses, scales, pauses, and undulating rhythms, held up on a poetic prose that will give shape to this germinal architecture. But, starting more or less at the book’s midpoint, the author becomes ever more committed to a narrative drive that will crescendo until it claims the starring role in the composition. And then, faced with the need to make story of song, proclaimed in a set of poems we might call intimate, we find the immigrant father, baby daughters adored unconditionally, twists and turns of childhood necessary if one is “to compete in other leagues.” After these memories, bit by bit, versification hands the reins over not only to flash fiction but also to flash prose (both are evident through the book’s later texts).

Lastly, I’ll mention two points I cannot omit. The first is on a vein I would confidently describe as “existentialist.” This narrator ponders themes that border on the drama of life. And, along with this revision of works and days, a second element runs in parallel like nutrifying sap: that touch of wonder, uncertainty, pain, and nostalgia; the validation of a hopeless hope. This is a tone. A color, perhaps, that imparts heat to everything it touches. And it does so with a (very) human voice.

When I finished reading the book the first time, I could not connect it to the confessional or conversational tradition of 1980s Venezuela. Rather, I noticed an echo of Jack Kerouac’s speedy prose in Tristesse and the buried screams of Charles Bukowski in the poems of Padecimiento continuo, where the melancholic use of irony shines through.

Upon subsequent readings, these affinities I thought I had found slipped away. I realized José Manuel has no such delirious or hallucinatory intentions. Nor does he interrogate or accompany another generation of poets or any particular tradition, although the street smarts of Venezuela’s “Tráfico” group perhaps gave him some pointers. His move, as I’ve said, is to prove that, indeed, “nothing’s going on here, it’s just life.”