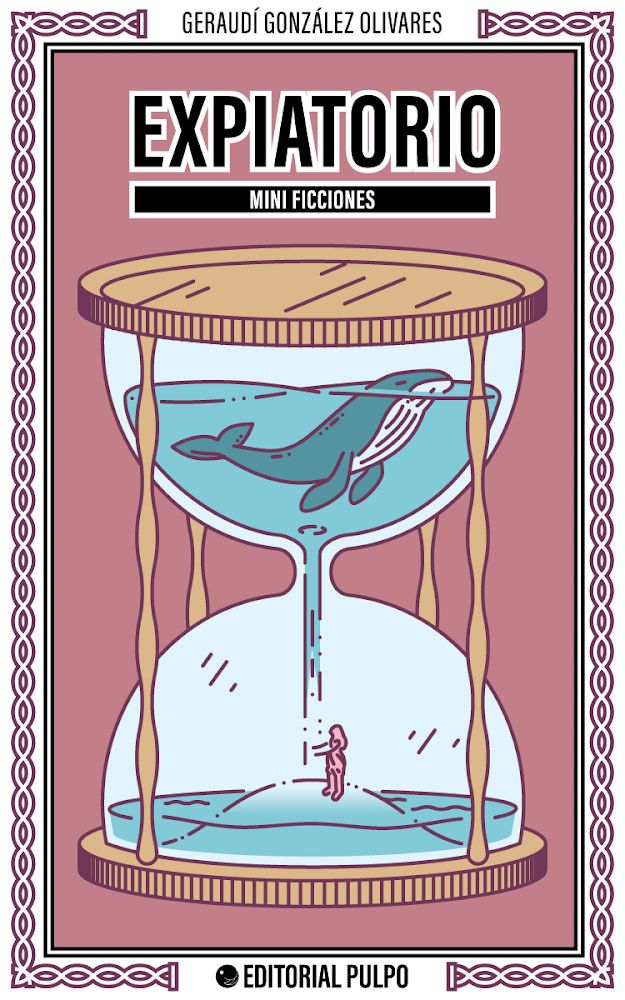

Puerto Rico: Editorial Pulpo. 2024. 46 pages.

Editorial Pulpo presents to readers Expiatorio, the first book of flash fiction by Geraudí González Olivares. Born in Venezuela and now living in Colombia, its author offers us an intricate literary universe—minimal, intimate, and immigrant—that connects its reader with multiple realities. Sometimes quite introspective, the perspective of its narrative voices—like the lens of a microscopic, always pointed and detailed—visits and explores complex feelings (loss, infertility, mourning, shortage, and emptiness) as well as other harsh social realities (migration, suicide, maternal filicide, and the abuses of the patriarchy, among others).

Editorial Pulpo presents to readers Expiatorio, the first book of flash fiction by Geraudí González Olivares. Born in Venezuela and now living in Colombia, its author offers us an intricate literary universe—minimal, intimate, and immigrant—that connects its reader with multiple realities. Sometimes quite introspective, the perspective of its narrative voices—like the lens of a microscopic, always pointed and detailed—visits and explores complex feelings (loss, infertility, mourning, shortage, and emptiness) as well as other harsh social realities (migration, suicide, maternal filicide, and the abuses of the patriarchy, among others).

With the steady hand of a surgeon and the powerful punch of a boxer, Geraudí guides us through her inner universe, granting us passage through the textures and bodies of other women authors just as she rewrites and converses with texts from varied traditions (literary, religious, and popular).

The quote with which the book opens, written by Geraudí herself, makes it clear where her writing is coming from in theoretical terms: these will be protean texts. There can be no doubt, they are able to take on linguistic and literary forms from other discourses and genres, to show us a way of looking at the world that is very much her own, but always from a perspective in movement, a perspective that is other… that is foreign.

With the first piece, “Posmoderno,” comes the first rupture, and thus we also find the first rewriting of a very well known female literary character. From a place of brevity—but, above all, of intertextuality—it is followed by forty pieces of flash fiction determined to break down various schemas. Short stories determined to shatter the patriarchal, chauvinistic expectations and roles that have historically been assigned to women’s bodies. The narrative voice makes intelligent use of texts and discourses that have always highlighted womanly faithfulness, purity, and chastity, for example, to put forth and uplift alternative values: necessary and distinctly human values, like pleasure and freedom. Thus, dialogues with and commentaries on other characters appear throughout the book—not only literary characters (like Penelope, Dulcinea, or Little Red Riding Hood) but also familiar characters (to the author, that is) and historical characters who allow the reader to navigate spaces that are tangible and intangible, real or fictitious. Consider, for example, her return to Venezuela’s indigenous origins through a woman character, as in “La búsqueda,” or her recovery and rewriting of other narratives, as in the case of a heroine of Colombia’s independence in “Nota de prensa en tiempos de independencia.”

“Reading these works of flash fiction is an act of expiation. This is a must-read collection that mends offenses, crimes, and misassigned guilts”

The narrative voices of Expiatorio are skillfully crafted to guide the reader in her travels through geographical spaces relevant to the author’s own biography (Valencia, Bogotá, the Cauca Valley). Nonetheless, many of these journeys also allow the reader to perceive new meanings in these spaces that have traditionally borne a specific weight for women, or have represented some sort of violence towards them (such as the taxi, the boxing ring, the house, the dining room, and the street, among others). What’s more, the way the author employs spaces and motifs such as the sea, bridges, rivers, the forest, and the nest gives rise to profound reflection and leads us to varied interpretations of relevant themes, both past and present.

The final pieces of flash fiction, called insomniacs, are told from the lockdown brought about by the COVID pandemic. These texts provide a masterful close to the reader’s expiatory experience. In them, the narrative voice emphasizes memories, shares episodes from childhood, and searches for ghosts of the past, returning to the masculine figure of the father. To return to him is to reconcile. This also means traveling back to the seed, to the starting point of the author’s relationship with literature and with her own writing. In short, Expiatorio is a book rich with apt and well realized metaliterary commentaries.

Geraudí comes to us as a writer experienced in handling intertextuality, as is so characteristic of this diminuitive genre. We are faced with an author who controls and cares for every detail. She shows it in her game of mirrors, in her selection and naming of characters and titles, in her dedications, in her flirtation with other literary genres (such as the instructional text). She also shows it in her handling of metaphor and paradox (especially in the texts dedicated to quarantine and lockdown). Other short stories, such as “Nido poético,” project the playfulness and poetic strength of Geraudí’s writing.

At the end of the reading experience—as it runs its course, that is—we also find the wink, the homage, the direct quote, always from the “fluttering of wings” and “the sacred feast,” from the “debate” and the “crossroads,” from contextures and the author’s fondness for the creative lives of other contemporary women writers. Expiatorio is a reflection on how to dwell in literary space and profoundly embrace writing… the process of creating in the feminine.

Reading these works of flash fiction is an act of expiation. This is a must-read collection that mends offenses, crimes, and misassigned guilts. This is a liberating read. Without a doubt, the readers of Expiatorio as well as its author, Geraudí González Olivares, come away absolved.