Colombia: Secretaría de Cultura de Pereira. 2023. 131 pages.

Just when we think we have gotten past a critical debate, a new outburst comes along to reopen the quarrel’s old cracks. This verse by Vicente Huidobro, revealing the binary existence of the adjective, now forms part of the Hispano-American literary reservoir: “The adjective, when it doesn’t give life, kills it.” Perhaps we have misinterpreted these words, since we no longer see any option but the autocracy of suppression. So goes the stigma: a formally correct poem, worthy of respect, must be wary of the adjective. Adjectivization, following these lines, walks close to something we do not want in the text, in the poem’s morphology. If this were true, the poet would be an epidemiologist concerned with detecting the frequencies of the adjective’s use—its propagation—and with treating, medically—which is to say verbally—its excesses and abundances.

Just when we think we have gotten past a critical debate, a new outburst comes along to reopen the quarrel’s old cracks. This verse by Vicente Huidobro, revealing the binary existence of the adjective, now forms part of the Hispano-American literary reservoir: “The adjective, when it doesn’t give life, kills it.” Perhaps we have misinterpreted these words, since we no longer see any option but the autocracy of suppression. So goes the stigma: a formally correct poem, worthy of respect, must be wary of the adjective. Adjectivization, following these lines, walks close to something we do not want in the text, in the poem’s morphology. If this were true, the poet would be an epidemiologist concerned with detecting the frequencies of the adjective’s use—its propagation—and with treating, medically—which is to say verbally—its excesses and abundances.

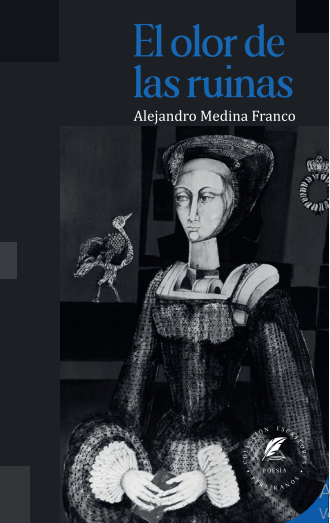

What would happen if the poet consciously thought not to limit the number of adjectives, but rather, in bold and effective fashion, dared to propagate a poetics of “excess”? This is precisely the first impression left on me by El olor de las ruinas by Colombian poet and short fiction writer Alejandro Medina Franco (1981). Medina Franco earned his master’s in Literature from the Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira and, for this book, received the 2022 Premio Colección de Escritores Pereiranos in the poetry category. He previously published the short story collection La mueca del gólem (2018). Adjectivization is a resource used agilely and often in El olor de las ruinas, unfurled in its currents of short verse. This spatial effect allows for another perception of the poems that, with conscious rhythm, give name to a transmuted, almost cubist everyday existence: “Mi brazo es corto, / y es uno, / sale del centro de mi pecho; / con él ha muerto / la bella simetría” [My arm is short, / and unique, / coming out of the middle of my chest; / with it, beautiful / symmetry has died].

“I HAVE RETURNED TO EL OLOR DE LAS RUINAS MANY TIMES, AND I WOULD NOT BE ENTIRELY WRONG TO THINK THIS ANTI-LYRIC VOICE IS SITUATED IN A WORLD LESS EQUAL THAN THE ONE WE LIVE IN”

El olor de las ruinas channels its influences with great accuracy—influences laid bare in epigraphs by Charles Baudelaire and Oliverio Girondo, for example, as well as those that work as invisible components but still hold up the poem’s foundations and columns. This aspect brings to mind several passages from the ruinous, criminal biography of Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, especially the decadence narrated in its first pages, which contextualizes the later events of the novel Perfume.

El olor de las ruinas imposes a way of understanding its author’s creative process. Perhaps this is a vice of mine as a poetry reader, but I like to see what motivations lie behind the isolated landscapes of the poem. I’ll explain: I like to see the discursive lesson the poem lays out before us. And, in Medina Franco’s case, the premeditation and free selection, his ability to choose: to play parqués on a chess board, to give name to cannibalism with highly cautious, anti-rhetorical language approaching stylized ugliness. All of this can be appreciated in the poem “Lepra,” read as a poetics. This is not far off from the words of Argentine poet Enrique Molina, referring to Oliverio himself: “He is not afraid to incorporate within his vision that which saccharine lyricism deems ugly. But this ugliness is nothing if not love for all the world’s forms, beyond their human connotations.”

I have returned to El olor de las ruinas many times—with eyes that seek to correct, and then with eyes that seek to appreciate—and I would not be entirely wrong to think this anti-lyric voice is situated in a world less equal than the one we live in, although this might be hard to believe: a postapocalyptic and cinematic world. A world that seems unprepared for both the good and the bad: a sanitary reality unable to contend with propagations and contingencies, much less with adjectivizations and their consequences in the creation of textual worlds.

Translated by Arthur Malcolm Dixon