Via Corporis. Pura López Colomé. Mexico City: FCE. 2016. 191 pages.

The Bodily Journey of Pura López Colomé

According to Cristóbal Pera, the act of surgery is often compared to the act of war: both involve risk, physical force, uncertainty, and luck. Surgeons invade their patients with the scalpel, following a map that leads them to the evil they must extirpate, while within the person who is invaded, “minimally,” there occurs an adventure with a good or bad ending that will be told by themselves, by their scars.

According to Cristóbal Pera, the act of surgery is often compared to the act of war: both involve risk, physical force, uncertainty, and luck. Surgeons invade their patients with the scalpel, following a map that leads them to the evil they must extirpate, while within the person who is invaded, “minimally,” there occurs an adventure with a good or bad ending that will be told by themselves, by their scars.

Illnesses and surgeries remind us of our passage through life. All of a sudden, in the midst of agony, our childhood identities reappear, our friends from infancy return, we rediscover the owners of the shops where we used to buy sweets, our parents when they were younger with all their scolding and shows of affection, the first friends we lost from sight, past lovers, random events that seemed completely unimportant at the time but that we pause over in retrospect, applying a magnifying glass and realizing that they were little epiphanies after all. We curse god, we regret, we converse with him whether or not we truly trust in his existence.

Via Corporis, by the Mexican poet Pura López Colomé, is a book in which pain is a manipulable material for the poetic I, which she forces to speak and speak until it is empty, until it halts the hemorrhage of any operation. The result is dispensable, it doesn’t matter if the body survives to spend a few more years in the world; what matters is telling the story, testing the language, laying it down on the operating table and scrutinizing it will surgical instruments. In the end, the words are also arteries: if they are severed, the pact with life is voided.

The book includes thirty-six poems that lead us down a path toward the history, memories, complaints, and questions of someone who is sick, whose survival is uncertain, who has undergone surgery. Perhaps we are faced with death, with the irrevocable loss of something within ourselves, and that’s why the ghosts of the past reinforce their presence such that we speak about them? What happens to us when we feel our wounds?

Language slips away from the López Colomé’s as if they were anaesthetized, about to go under the surgeon’s knife. They let themselves be carried away by language, and they fear it, they reveal their vulnerability: “Divided into quarters or pieces, the animal poem of a person carved up. Astonished.”

Whether written in impeccable hendecasyllables, free verse, or prose, the distinct and fluctuating registers of the texts are similar to the pulse and the flowing blood of a living organism. They also bring to mind the internal monologue that connects the past and the present, since the future can only be known when we insert our finger into the hemorrhaging opening: “I intuit with disappointment / that it is too late / to find the guide / who puts on a brave face / in my dark times.” In sickness and in health, were are subjects of defencelessness; at any moment and for any reason, be it physical or by the forces of nature, our fate can be reversed and we can be condemned to alienation. We look at ourselves in the mirror, but we never know what we are. The only possible threads along which to move in the scene of simulation come from language. Pura López Colomé reveals this constantly: “I feel, at night, the stab / of an image / edited / specifically / to thrust its dagger, / to divide shots or entire scenes of the happy happenings of dreams.”

It requires a measure of bravery to read this book from cover to cover; there are no calm poems here, all are heart-rending. The poems of Via Corporis are not the microscope slides they gave us in elementary school for science class. Sometimes you must take the time to return to these texts, because they leave the reader absolutely defenseless. Even after reading only a few verses, body and soul begin to open. There is irony and a dose of humor, but always, once the incision is made, the reader inevitably feels that something is about to be extracted. Pura López Colomé sutures together life, flesh, and word. Her poems remind me of those photos proudly shown to me by one of my best friends, a surgeon, in which you could clearly see some throbbing organ.

Via Corporis is a sort of medicine for our wounds, an exploratory technique of trial and error, of unease and self-discovery. What does it matter if there is life after death? The suffering of language is defense enough, even when it seems useless: “It seems I am writing a testament / behind powerful acts, / with my tear ducts covered over by salt, / the bad luck of having been nothing, / while the storm and its spectres / lash the unbelievers.”

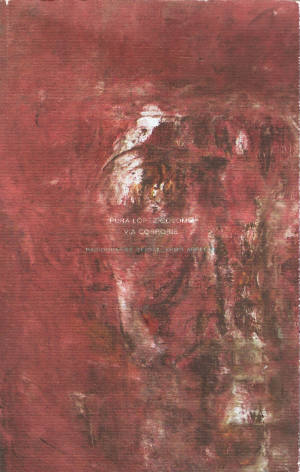

Finally, I must give special mention to the images that accompany the poems, all of which are by the self-taught Mexican painter Guillermo Arreola. Alfred Corn describes his work as something to be confronted with fortitude and courage, and this definition could not be more accurate. López Colomé’s poems are accompanied by acrylics painted on strips of radiographic film (that’s why they’re called radiographs), and the collection of images is called Sursum corda (“Lift our hearts”). Head, heart, ribs, the deformed body, questioned and defenseless: each illustration exposes its furor, its fragility; the chosen colors make the potency and agony of the sick body all the more visible. The dialogue established between Arreola’s radiographs and the poems reinforces the bodily journey. We are carried away by the fascination and fear of looking into the opened organism, put bluntly, with tendons and entrails exposed. The abysses of human anatomy, along with the need of the being to be recognized and reconstructed when suffering attacks, are presented in a form that is both vulnerable and imposing.

Lorena Huitrón Vázquez