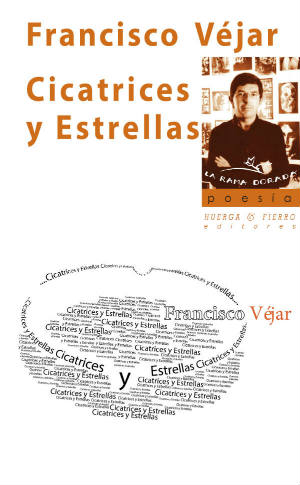

Cicatrices y estrellas. Francisco Véjar. Madrid: Huerga y Fierro Editores. 2016.

Cicatrices y estrellas [Scars and stars] (2016) is a brief, but subtle and beautiful, collection of poems by the Chilean poet Francisco Véjar: an anthology published as part of the “La Rama Dorada” collection by Spanish press Huerga y Fierro. The book contains twenty-five pieces of a poetry purified by the passage of time in which readers familiar or unfamiliar with Véjar’s work can appreciate a speaker who, in each text, reveals his “wounds and brilliance,” as if in a moderato cantábile or the title of a “theme” of cool jazz, a musical form that both attracted and recalls this author. From these remembrances and from other cultural references (not only musical), this verse collection is constructed as reflections and resonances of the life of its author and of his poetic conception, as if it were the soundtrack of a film, at once visceral and melancholy.

Cicatrices y estrellas [Scars and stars] (2016) is a brief, but subtle and beautiful, collection of poems by the Chilean poet Francisco Véjar: an anthology published as part of the “La Rama Dorada” collection by Spanish press Huerga y Fierro. The book contains twenty-five pieces of a poetry purified by the passage of time in which readers familiar or unfamiliar with Véjar’s work can appreciate a speaker who, in each text, reveals his “wounds and brilliance,” as if in a moderato cantábile or the title of a “theme” of cool jazz, a musical form that both attracted and recalls this author. From these remembrances and from other cultural references (not only musical), this verse collection is constructed as reflections and resonances of the life of its author and of his poetic conception, as if it were the soundtrack of a film, at once visceral and melancholy.

Francisco Véjar’s poems have the rhythmical subtlety of Miles Davis’s trumpet, with which the U.S. musician invented cool jazz, not pushing down the keys of his instrument all the way. Véjar’s poetry is like the sound of Miles’s trumpet in his early years: a harmony that emulates cool jazz and enters into spaces that hang as if suspended in a lost time, in a memory that permanently recalls and persists in a life, sometimes present, that is rather cruel. The poet speaks of lost loves, or of loves that emerge like ghosts in his ever-desirous verses, loves that reappear at the last stop of the metro, in a hotel room where the body of the beloved replaces reality; places where one escapes from love “as if from a plane crash.” In these poems, love is always memory as well as longing. We read lost loves, witnesses of survival without lyrical stridency, baroque scripture, or delirium tremens, even when the presence of alcohol is suspected. We intuit that Véjar’s speaker addresses us from a wound, like in the famous monologue by Manuel Rojas in Hijo de ladrón [Son of a thief] – “let us suppose that I have a wound” – but, unlike in Rojas’s text, this speaker does not display his wound to the public.

I believe it is precisely in the silences or the sotto voce, in not fully depressing the keys of the trumpet, in every suggestion that makes his textuality belong like a message in a bottle that never stops foundering, where the sense of this remarkable poetry resides. In it, we can sense the presence of a wounded man through all these symbols: lost hotels, “coves” like the one at Quintay, sleeves of old Stan Getz LPs, metro stations after a melancholy workday, landscapes that are illuminated but no less evocative of the persistent wound. And this perspective engages, as I said, with certain hotels, fishing villages, big cities, lonely beaches, and other landscapes as sketches of a reality through which Véjar converts his inward gaze into poetry.

A perspective of great poetic intensity, facing the heart of the speaker, not of his darkness, but of a man who has lived a great deal and wants to transform that vital intensity into a whole world of words. It is that world so particular to Francisco Véjar, so much his own, of poets and musicians and films, with which he converses. These elements are also firmly settled into his poetry, in which we find so many absences, above all of lovers who, for one reason or another, abandoned him. The main one, of course, is paradoxically death itself; he writes: “It’s true, if poetry were real / you should be here.” These verses appear as a notable discovery, making us “feel” the solitude of the speaker who, despite giving off so many forms of beauty (making us feel the absence of the beloved is just one of them), undoubtedly ensures that Francisco Véjar’s poetry be the expression of a man who loved, not few or “the one,” nor all or many. All of this to finally construct an archetype of the absence that fills itself with the teachings, the memory, the silenced voices, the landscapes revisited à la Proust, of those loves that have, in many ways, torn apart his words, just as they have put together the surface of the poem. So, this book can be read as a fragmentary whole of that miracle that is survival through the word, despite the fragility that verse by verse, poem by poem, is expressed to us.

All true poetry, I believe, is personal, lyrical, and subjective; it engulfs us through its textual practices. In Véjar’s case, music is like a sigh; his flaneurism, just the same, on walks that leave no footprints and gazes that, if left behind, are the setting for each statement that tells us of the woman and her absence, of permanent death and its consequences, of the “pained feeling” and its shadow, the landscapes like calm watercolors. Examples include the poems “Resplandor” [Radiance], “El viento” [The wind], and “Lo que no alcancé a escribirte” [What I didn’t manage to write you]. In these temples, in these statements we can see how the wounded hand, or the hand of the wounded, trembles. Or the hand that tries not to tremble but can’t help it, because “it has a wound” that transforms it into a poetry as quotidian as it is ghostly.

The unsaid, the intuited, the whispered is the strength of Francisco Véjar’s poetry. A suspicious and sensitive reader will be able to unravel “a hundred syllables […] encoded, furtive, with collapsing houses and wounds in the sidewalk.”

Among secrets, birds, transparencies, walks, gazes, and melodies, we flow like a river into the poem that forms the irrigating heart of this book’s wound: “Estación Leopoldo María Panero.” Certainly, Francisco Véjar is not a poet of dysphoric madness, like Panero: there is no delirium or delirium tremens in his verses, nor are there nihilist storms that leave him on the edge of emptiness or Artaudian madness; but in this book he shows us, or demonstrates, that his words stand with their feet on the edge of the cliff. This final poems tells us so: “Estación Leopoldo María Panero / all that I write and descry / goes to the base of the blood.”

Thomas Harris