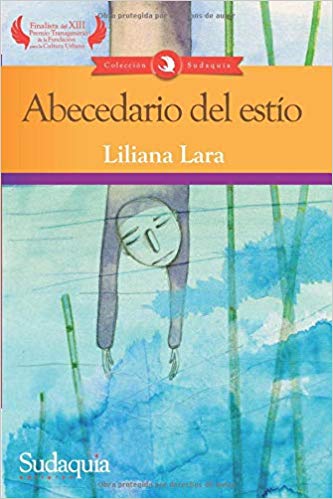

Abecedario del estío. Liliana Lara. New York: Sudaquia. 2019. 135 pages.

To write an ABC is to give in to the temptation to recreate a world from A to Z. The choice of word to represent each letter draws a map of what we are, what we have been and, perhaps, what we would like to become. That is the task Liliana Lara sets herself in her Abecedario del estío (An ABC of Summer): to recreate a world out of fragments, which takes us on a journey far beyond the 27 letters of the Spanish alphabet. It is a skip through the fears and the dreams, the memories and the books, the resolutions and the phobias that frame the life of a foreigner of Venezuelan origin, who lives in an Israeli kibbutz, on the edge of a permanent war zone.

To write an ABC is to give in to the temptation to recreate a world from A to Z. The choice of word to represent each letter draws a map of what we are, what we have been and, perhaps, what we would like to become. That is the task Liliana Lara sets herself in her Abecedario del estío (An ABC of Summer): to recreate a world out of fragments, which takes us on a journey far beyond the 27 letters of the Spanish alphabet. It is a skip through the fears and the dreams, the memories and the books, the resolutions and the phobias that frame the life of a foreigner of Venezuelan origin, who lives in an Israeli kibbutz, on the edge of a permanent war zone.

In the 27 chapters of the book, which maintain the freshness and immediacy of the blog entries on which they are based, Liliana Lara offers us a universe which extends from the A for Agua (Water) to the Z for Zapatos (Shoes). Essay combines with reportage, poetry with review, to offer us an exchange that is very close to complicity. They are texts in which the Israeli landscape merges with the origins in Maturín that the foreigner keeps in her memory, and with all the possibilities of living at a cultural crossroads. Through this series of disparate texts travel the sayings, fears, and moments of conformity and rebellion of someone who adapts to, bends to, and resists a new culture in equal measure.

In that ragbag where anything goes, it is the flow that prevails. There is space for everything from religious fanatics to survival classes, from imaginary pets to bomb sirens, from the difficulty of expressing yourself in a language that is not your own to conversations at the hair salon, passing through a poem about freebies and touching on the impossibility of naming those tiny insects that you don’t know what to call in any language. But there are also the points in which everything pauses. Like at a bus stop where two nomads, who look like two picture cards of Jesus come to life, talk about their journeys around the world. Or the office where you must go to sign a statement of unemployment. Or the booth where there is always that one employee asking for your name. Spaces where the foreigner defines herself at the same time as she loses definition. Places that give way to reflection on the experience of not belonging, of not sharing the same codes as everyone else, of not really knowing the correct response to any moment, and yet still being able to be amazed and to tell the tale.

Because there are also those moments when memory comes to the rescue in the form of one of her grandmother’s sayings, a sudden resemblance to her mother or father, or the borrowed recollection of a life that is not her own. Memory acts as the place where the foreigner reencounters a center, which seems fixed, bright and green like the map of her native city that she has stuck up on the kitchen wall. And there are also the books which accompany and explain, illuminate and push, offer paths and other ways of living. Among these books are other ABCs: that of the Polish poet and Nobel laureate Czesław Milosz, and that of the Israeli author of Polish origin Dan Tsalka, inspired by Milosz’s text. One of the most experimental ABC writers in the Spanish language, Bernardo Atxaga, also appears.

While the ABCs written by these authors tend to be populated with historical events and notable people, Liliana Lara’s work with letters focuses on the intimate. “My ABC”, she says in the chapter titled M for Milosz, “is, above all, selfish.” She adds, “I, who has never wanted to write autofiction, here I am, inventing myself.” It is true that what this narrative voice does is invent itself, but along the way what it offers us is not a stubbornly inward-looking gaze, rather a journey full of surprises, which inhabit the spaces that the narrator shares with many other characters who pass through or stay a while. They help us to recognize the experience of being uprooted, but also to give a chance to the possibility of living with others and establishing new roots.

These roots grow primarily in the home and the family. A partner and children who seem like the universe from which every experience emerges and expands. The domestic space where daily tasks are completed, and small everyday discoveries are made that give meaning to existence. The children who dream, who make demands, who take up time, but who also give joy and throw out handfuls of curiosity that brightens everything it touches. The school where, inevitably, you must meet other parents. The park in which other mothers, accompanying other children, chat at a vertiginous speed. It is in this universe of the everyday, which is the first anchor for any foreigner, where the text lingers most. But it goes further, burrowing into the complicity of kindred characters, who speak the same language, such as the Palestinian woman of Peruvian origin who calls from the other side of the border to order supplies in the midst of unending bombing. And still further, showing the bus journeys to Jerusalem, and arriving at the bus station, in which objects and people cross in a jumbled hodgepodge that decenters the experience of the foreigner who watches and recounts like someone who entered the city by the back door.

By using the ABC format, Liliana Lara discovers a way of putting together the jigsaw puzzle that is the elusive identity of someone who has been uprooted. At the same time, she distances herself from the writing which dramatizes the experience of uprooting, to offer us a lighter tone that allows us to glimpse the benefits and blessings of not belonging. This book is a map that takes us through the minefield of uprooting without falling into the traps of sentimentality, aware of the risks, but prepared with a spirit of play to not get trapped in the treacherous river of nostalgia.

Raquel Rivas Rojas

Translated by Katie Brown

Raquel Rivas Rojas is a Venezuelan writer and translator. She has published the essay collections Sujetos, actos y textos de una identidad (CELARG, 1998), Bulla y buchiplumeo (La Nave Va, 2002), and Narrar en dictadura (El Perro y la Rana, 2011), as well as a short story collection, El patio del vecino (Equinoccio, 2013) and two novels, Muerte en el Guaire (Ediciones B, 2016) and El Accidente (Bichos de la Orilla, 2018). She lives in Edinburgh and runs the blog Cuentos de la Caldera Este.

Katie Brown is a Lecturer in Latin American Studies at the University of Exeter. She completed a PhD on “The Contested Values of Literature in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela” at King’s College London. With Tim Girven and Montague Kobbe, she co-edited the anthology Crude Words: Contemporary Writing from Venezuela (Ragpicker Press, 2016), for which she translated stories by Rodrigo Blanco Calderón, Héctor Concari, Liliana Lara, Carolina Lozada, Juan Carlos Méndez Guédez and Slavko Zupcic.