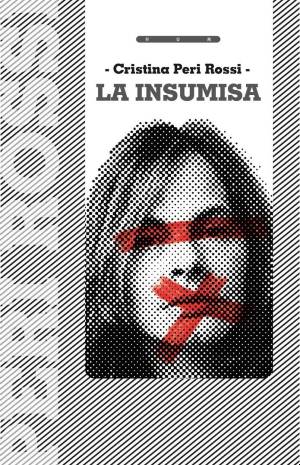

La insumisa. Cristina Peri Rossi. Montevideo: Hum. 2020. 215 pages.

Cristina Peri Rossi is a girl that writes as an adult, trying to explain to a girl—who isn’t a girl anymore, but who really still is—the incomprehensible reason that made her stay a girl, now eighty years old. This leads her to ask herself everything that she ever questioned. Family, a woman’s role in Uruguayan society in the middle of the twentieth century, finding love, coming to understand herself as a lesbian, and the importance of writing compose the thematic ensemble that matches a solemn impression. Her rebellion in childhood and adolescence is the neurological center of the autobiographical novel La insumisa, published shortly after the author received the Premio Iberoamericano de las letras José Donoso award in 2019.

Cristina Peri Rossi is a girl that writes as an adult, trying to explain to a girl—who isn’t a girl anymore, but who really still is—the incomprehensible reason that made her stay a girl, now eighty years old. This leads her to ask herself everything that she ever questioned. Family, a woman’s role in Uruguayan society in the middle of the twentieth century, finding love, coming to understand herself as a lesbian, and the importance of writing compose the thematic ensemble that matches a solemn impression. Her rebellion in childhood and adolescence is the neurological center of the autobiographical novel La insumisa, published shortly after the author received the Premio Iberoamericano de las letras José Donoso award in 2019.

The novel constitutes a series of anecdotes that shed light on past interests; that is to say, the obsessions in Peri Rossi’s work are directly related with lived experiences during her childhood and youth, now connected with life and artistic creation, presenting them as a single organism incapable of dissolution. Those vital themes and experiences not only formed the young author’s emotional education; they are evoked from a more mature age as a biographical testament and a way of understanding her work, the first impulses and analog of her creative practice.

Meditation about the writing itself and of conceiving of herself as one who wanted to be a writer, like a vital end or mission, appears in the form of the adult Cristina Peri Rossi. She travels the span of her eighty years, speaking with the girl that she was, who once lived the experiences that, despite not having understood them at the time, sealed and molded within her an artistic character that accompanies her to this day.

The stories work by sharing the search for the beginning and the mechanisms of creation in the shadow of incomprehension. She distances her interests from those of her family and tries to survive emotively off of the difference in mid-twentieth century Uruguay. Far from orality, close to an archetypical literary classic, La insumisa is characterized by a novelistic narrative of stories that preponderates over the reflection of autobiographical writing as a form.

Uruguayan criticism has celebrated the novel, which already considered the author’s work as part of a hegemonic national canon. Its reception could be a perfect excuse to revisit some examples of biographical writing. The characteristics of those texts can give an accounting of the creative processes that cause differences, similitudes, and nuances; results that are beyond the raw material, revealing that the importance that is always rendered to content is less important than the rendering.

Despite being an approach or theme that specialized Uruguayan criticism continues to question, and that some authors with a certain national relevance dismiss, Uruguayan biographical literary materials are not new. There are examples that can serve as a point of reference. These include the narrative work of Roberto Appratto or the fragmentary novels of Alicia Migdal, they work as an antecedent for subsequent generations, keeping in mind that accepting certain foreign reference never was, nor will be, a simple possibility.

In 2019 and 2020, Alicia Migdal, as well as Hugo Achugar and Roberto Appratto, edited novels that begin with or relate to their own biographies, albeit with distinct tones and focuses. It might seem obvious, but in a country where the first person remains audacious—when it comes from one’s own countrymen—some more experienced authors that remain in close proximity to other generations still dare to start out with biography. It’s a risky bet, even though it’s a tool that they’ve been perfecting since the beginning of their careers. Other authors that have flirted with biography or the so-called “I” writing in recent years are Fidel Sclavo, Carolina Silveira, José Arenas, and Fernanda Trias.

Perhaps without trying, La insumisa is one more piece that helps to understand—or to stop trying to understand and just observe—the details of biographical structures as a body of work that persists in Montevideo’s literary field. Peri Rossi’s voice, distant and removed, returns in continuous thought to the softly undulating country where she was born, to accompany a form of the ineffable: doing whatever she wants without caring what they’ll say.

Leonor Courtoisie

Translated by Michael Redzich

Leonor Courtoisie dedicates herself to the practice and research of the performing arts, cinema, and literature. Someone once told her she could do things that don’t exist, and she tries to follow this advice. She coordinates Salvadora Editora and forms part of Sancocho Colectivo Editorial. She collaborates with Semanario Brecha. Her book Duermen a la hora de la siesta was awarded Uruguay’s Premio Nacional de Literatura in 2019. She also received the Molière Prize, awarded by the French embassy. She is a member of the Lincoln Center Directors Lab in New York. She recently published Corte de obsidiana (2017), written during an Iberescena residency in Mexico, and Todas esas cosas siguen vivas (2020). She writes, acts, revises, directs, and edits every day.

Michael Redzich is currently studying law at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. He graduated from the University of Oklahoma in 2017 with a BA in Spanish and a BA in Letters. His interest in Latin American literature sprouted early in his Spanish education, but grew considerably during his time in Buenos Aires, where he lived from 2014-2016. Michael was one of the first OU undergraduate students to become involved with LALT, upon which he continues to work as a translator and editor at large.