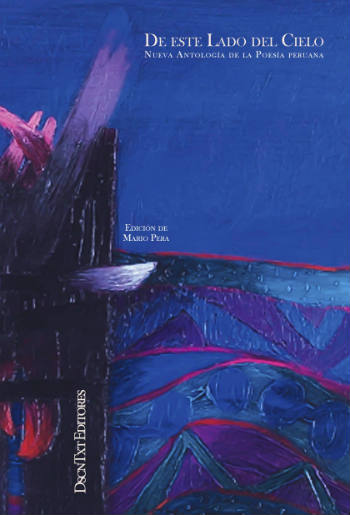

De este lado del cielo: Nueva antología de poesía peruana. Edited by Mario Pera. Santiago de Chile: Descontexto Editores, 2019. 512 pages.

If Peruvian poetry begins with Manuel González Prada, José María Eguren and José Santos Chocano and today encompasses poets Miguel Ildefonso, Victoria Guerrero and José Carlos Yrigoyen—as in the anthology De este lado del cielo [On this side of the sky], edited and with a prologue by poet Mario Pera—then we can discuss it as an enduring exercise whose creative language uses innovation and history to plot texts that are truly pleasurable to read.

If Peruvian poetry begins with Manuel González Prada, José María Eguren and José Santos Chocano and today encompasses poets Miguel Ildefonso, Victoria Guerrero and José Carlos Yrigoyen—as in the anthology De este lado del cielo [On this side of the sky], edited and with a prologue by poet Mario Pera—then we can discuss it as an enduring exercise whose creative language uses innovation and history to plot texts that are truly pleasurable to read.

If, from start to finish, Blanca Varela, Carlos Germán Belli or Rodolfo Hinostroza set the rhythm, then the reader’s enthusiasm builds as he keeps the beat with his gaze, and by design he arrives at the happy event—tragic, but happy for us, his readers—of César Vallejo’s works, it becomes clear that the publication of this anthology is a major event.

One hundred thirty-two years passed between the birth of the first author and that of the last of the 69 poets chosen for this collection. For any country, a century of works is more than sufficient, but in this particular case, I believe a longer period would have been even better, given that in his prologue Mario Pera explains the periods, processes, and primary players in the Peruvian nation’s poetic history. The colonial dependence that a Viceroyalty—a heritage that rubs a wound—leaves in the bones of the language, a legacy that continues to splinter with each new advancement, until la vanguardia breaks those bones, is defined by its contradictions. As Sebastián Salazar Bondy suggests, “My country is an intense passion, a mournful sea, a tireless spring/of fermenting races and myths.” This is what great poetry is: universal in its own universe.

The book’s ample format in particular allows us to appreciate lengthy texts, within which the development of a variety of aesthetic proposals is grounded. This was an excellent stylistic choice as the editor curated the volume. Perhaps this point leads us to the selection criteria, since—although history eventually canonizes names and works—it’s no less true that the anthologizer can and should undertake a critical process that, at minimum, highlights the line or lines that best define a work.

Therefore, in spite of—or due to—issues of length, it’s appropriate to survey this long list of authors since this is, in fact, the primary point. Eight authors were born prior to 1900: Manuel González Prada, José María Eguren, José Santos Chocano, Abraham Valdelomar, César Vallejo, Juan Parra del Riego, Gamaliel Churata and Alberto Hidalgo. Magda Portal was born in 1900. With Vallejo we know that there’s a before and an after, or an after and an after. In strictly chronological order, he is followed by César Moro, Enrique Peña Barrenechea, Xavier Abril, Carlos Oquendo de Amat, Martín Adán, Emilio Adolfo Westphalen, Raúl Deustua, Jorge Eduardo Eielson, Javier Sologuren, Sebastián Salazar Bondy, Julia Ferrer, Efraín Miranda, Alejandro Romualdo, Blanca Varela, Washington Delgado, Carlos Germán Belli, Francisco Bendezú, Juan Gonzalo Rose, José Ruiz Rosas, Pablo Guevara, Cecilia Bustamante, César Calvo, Walter Curonisy, Guillermo Chirinos Cúneo, Juan Cristóbal, Luis Hernández Camarero, Rodolfo Hinostroza, Antonio Cisneros, Javier Heraud, Manuel Morales, Enriqueta Beleván, Juan Bullita, Juan Ojeda, Jorge Pimentel, and José Watanabe—who, like the majority of those aforementioned, is deceased, but who makes it nown—or would that be after Hinostroza?—that there is a solid and sustained generation of contemporary poetry in Peru. He’s followed by Óscar Málaga, Juan Ramírez Ruiz, Mirko Lauer, Carmen Ollé, María Emilia Cornejo, Enrique Verástegui, Yulino Dávila, Carlos López Degregori, Giovanna Pollarolo, Marcela Robles, Mario Montalbetti, José Morales Saravia, Roger Santivañez, Magdalena Chocano, Dalmacia Ruiz Rosas, Eduardo Chirinos, Mariela Dreyfus, Juan de la Fuente, Rafael Espinosa, Rodrigo Quijano, Monserrat Álvarez, Martín Rodríguez-Gaona, Miguel Ildefonso, Victoria Guerrero and José Carlos Yrigoyen.

The selections’ variety and scope unfold as the concept of language complexifies the incorporation of its visible elements into the text’s composition, so that authors including Lauer, Ollé, López Degregori, and Montalbetti proceed toward poems that make more reference to their own composition than to the Peruvian being who moves, so to speak, toward a heaven ample enough to hold all the stars. This (pre)disposition also allows us to appreciate the historical changes that have taken place in the positioning of writing. From the center—Lima—toward marginalized barrios, toward provinces that intuit their own ways of speaking. From avant-garde individuality to conceptually self-referential groups like Hora Zero, or, later, el Movimiento Kloaka, history continually permeates the present. Thus, the reader’s enjoyment outlines a strategy for reading cultural–or countercultural, in this case—processes and the ways in which they disrupt Peruvian poetry’s framework.

About a decade ago, in 2008, thanks to Carmen Ollé’s anthology Fuego abierto, we began discussing the prevalence of ideas over a poetics that copies stories from what we call reality, whether it’s actually real or not. Yes, in that literary precursors in experimentation have existed since Churata’s Andean vanguardismo, from Carlos Oquendo’s 5 metros de poema, through Hinostroza’s Contranatura, to Montalbetti. No, because the authors—even in Hinostroza’s later work—as well as Peru’s present and past, continue to play an essential role in the writing: Manuel Scorza’s social poetry; Blanca Varela’s so-called virtuous aesthetic; and Montserrat Álvarez’s sarcasm all derive from being read with attention to the social and biographical bodies that they reference. Mario Pera successfully synthesizes this rhythm in his extensive prologue and justifies reading this work in sync with that same beat. Defending specific criteria is one thing, but embodying them is another. In the words of Pera himself, “Those works witness the representation and influence of some poets of their era, as well as the aesthetic value of their work, the historical courage needed to create new forms of poetic expression or, in my criterion, forms that are better realized. Finally, I intend to make the outer edges of the poetry written in Peru visible, those that converge or diverge in keeping with their circumstances.”

For us, this has been a positive opportunity to rediscover authors who are read as individuals, on their own, and who ultimately comprise a whole that persists across time. A deeply rooted and tenacious undertaking whose result is a solid, historic, and nuanced work. De este lado del cielo, Mario Pera’s anthology, is, beyond any doubt, a book to be read anywhere.

Sergio Rodríguez Saavedra

Translated by Karen Martin