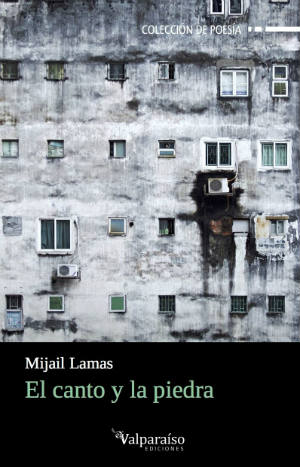

El canto y la piedra. Mijaíl Lamas. Mexico City: Valparaíso. 2017. 63 pages.

Every poem pays a double homage. It goes, on the one hand, to the texts that came before it, since it is nourished by subjects already visited countless times. On the other, if goes to the life of the author. Every idea spilled out in the poem tends to reveal tastes, readings, maybe even negative aspects of the poet himself. I’m thinking of Bonifaz Nuño in El manto y la corona [The cloak and the crown] (1958) and Eduardo Lizalde in La zorra enferma [The sick fox] (1974). Both poets display a remarkable approach to the Greco-Roman tradition, hoping to validate it in Mexican poetry, but they do so in different ways, according to their personalities: the first prefers the love poem, the elegy, placed in an atmosphere near to the man in the street; the second prefers the biting, epigrammatic poem, in the voice of a poet who doesn’t believe in the great values of his time. El canto y la piedra [The song and the stone] (book number 45 from Valparaíso México) by Mijaíl Lamas is a poetry book whose verses can be linked to those of Bonifaz and Lizalde, as much for its interest in returning to Greco-Roman tradition as for its contemporary Mexican context, as well as its use of tone, moving from the melancholic to the ironic and passing through the celebratory on the way.

Every poem pays a double homage. It goes, on the one hand, to the texts that came before it, since it is nourished by subjects already visited countless times. On the other, if goes to the life of the author. Every idea spilled out in the poem tends to reveal tastes, readings, maybe even negative aspects of the poet himself. I’m thinking of Bonifaz Nuño in El manto y la corona [The cloak and the crown] (1958) and Eduardo Lizalde in La zorra enferma [The sick fox] (1974). Both poets display a remarkable approach to the Greco-Roman tradition, hoping to validate it in Mexican poetry, but they do so in different ways, according to their personalities: the first prefers the love poem, the elegy, placed in an atmosphere near to the man in the street; the second prefers the biting, epigrammatic poem, in the voice of a poet who doesn’t believe in the great values of his time. El canto y la piedra [The song and the stone] (book number 45 from Valparaíso México) by Mijaíl Lamas is a poetry book whose verses can be linked to those of Bonifaz and Lizalde, as much for its interest in returning to Greco-Roman tradition as for its contemporary Mexican context, as well as its use of tone, moving from the melancholic to the ironic and passing through the celebratory on the way.

El canto y la piedra is divided into five parts: “Materia” [Matter], “El canto y la piedra” [The song and the stone], “Órficas del Hades” [Orphics of Hades], “Los dioses personales” [The personal gods], and “Final” [End]. The first two, which include a total of three poems, can be considered the book’s opening, as they celebrate song as a way of naming the world, the act of writing and the importance of the poet’s word as a way to transcend mortal time. Without these elements, as Lamas seems to tell us, it is impossible to concretize the poetic task.

The third part is the longest and the most realized of the five, and I believe it constitutes a small but important contribution to that current of Mexican poetry that seeks to mine into classical literature, to find within it some precious metal. In this sense, Lamas has found something valuable: a chronicle of contemporary depression, founded in failure, and how this is manifested in various spaces of everyday life. To do this, he starts with the myth of Orpheus and his journey to the underworld, reinventing its characters: Orpheus is an office worker, Eurydice is his lover who left three months ago, when they call her she hangs up the phone. The underworld isn’t a specific place, but rather the depression that Orpheus suffers: like a dense shadow, it covers the bar, the office, even his house. In his book Darkness Visible (1990), William Styron describes his relationship with depression as “penetrating in the shadows of the afternoon with their subjugation of anxiety and fear… my thoughts sank under a toxic, inexpressible tide that obliterated any pleasant response to the living world.” Lamas’s Orpheus seems to live a process of spiritual decomposition similar to Styron’s, which is reflected in the place he lives, and which ends up destroying his daily routine: “Three months have passed since you left / and I keep preparing / two cups of tea in the morning. // I always drink the one you won’t. // Three months have passed and for two weeks / my clothes have been dirty, / the garbage piles up everywhere / and old Cancerbero, who is almost blind, / has started barking at me when I get home.”

The poem “XX,” which is the final chapter of the main character’s story, but not of the section, is important for the closure it proposes in the form of a debate between a happy ending and the prolongation of mental suffering: “The whole room has become luminously dark, / I’ve dreamed about you, / very slowly you tell me: I’m finally back.” Lamas ends the poem in the lowest place of the underworld, the moment of truth, when the lover is about to awaken: or indeed the beloved is there and, finally, life and souls return to their normal course, or everything was a dream and the voice we hear is that of still unfulfilled desire.

The fourth part of El canto y la piedra consists of several ludic poems that highlight the book’s nature as a successor of traditions and matters conscious of the events of a specific time. The texts here extend their references to the culture of rock music, as if Lamas were telling us that we can still hear reminiscences of the song of Orpheus in the songs of this musical genre. In “Janis,” the voice of Janis Joplin invites the poet to learn that he has become an everyday working man, but soon the poet moves away from Janis’s voice and concludes by rejecting his desires to throw everything away. Meanwhile, in “Peter Pan reclama” [Peter Pan complains], the songs of Nirvana are the only defense charm against the empty office life. “Nevermind,” which references Nirvana’s second album, is a tragic chronicle of the early nineties: the death of Luis Donaldo Colosio, the genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda, NAFTA.

The final section, subtitled “Del anti-Orfeo” [On the anti-Orpheus], is a return to the plot of the third part of the collection. We return to Orpheus, who is now explored through his song itself. The result is a reflection on the task of the poet in modern times. For Lamas, to approach the poem is to come to terms with our current condition on the planet, and to know how we relate to each other as a society: “because I am awake every morning like he who died days ago.” This is the poet we meet through reading El canto y la piedra, an Orpheus in the sense that his present has become a journey to the underworld. But also an anti-Orpheus because, unlike the mythological hero, his song does not calm beasts or save anyone. Rather, it only exists and is heard in order to reveal its own presence in the world, a presence marked by the joys and woes of everyday life.

Marco Antonio Murillo

Foundation for Mexican Letters