For a long time, I woke up in utter fear. Every morning, panic would take over my body as I listened to a sound that was different from my friends’ alarm clocks. It wasn’t cocks crowing, or my mom’s subtle words, or the beeping of a wristwatch alarm. What woke me up was my uncle, who repeatedly howled his own name: Raúl!, Raúl!, Raúl!

And it was with that yelling that I would quickly get ready for school.

“Good morning, son. Say goodbye to your uncle,” said Virginia, my mother, when we passed by his side on our way out.

I asked him for his blessing as he laughed hard. Sometimes he would hug me so tight that I felt like he could break my bones.

“God bless you! I love you,” he would reply.

His words of affection appeased my fear. Most of the adults in my house pronounced those words at one point or another. To me, those words meant family, and we tend to think that family would cause you no harm. I was five years old then and I didn’t really understand what was going on.

However, fear would haunt me again as soon as I got home.

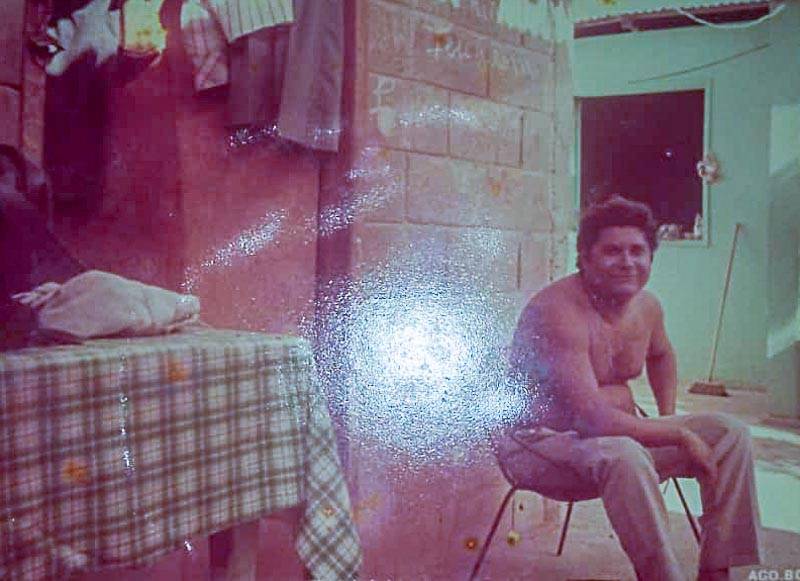

Raúl could scare anyone. He was tall, white-skinned, fat, and had a mysterious look. He wore loose-fitting clothes and rubber flip-flops that made a lot of noise when he walked. He spoke loudly. He was very strong. Sometimes I thought he was the Hulk, only he wasn’t green.

When I grew up, they told me his story. They say one drink changed his life.

No one exactly remembers the night that Raúl, 17, was having drinks with a group of friends. Some of them were playing dominoes. It was that night in the La Trinidad neighborhood of Cumaná, the capital of the state of Sucre, when someone offered him rum. And he accepted.

After a while, he started running up and down the street, as if he was enraged. His breathing changed, his gaze changed, he looked desperate. People in the community were baffled, and not even Raúl’s parents, my strong-charactered grandparents, were able to control him.

Until he came down with a fever and grew very quiet.

Word spread that Raúl was acting like that because the rum he drank had been adulterated. His parents, stunned by such behavior, decided to take him to the doctor. He was examined and ordered some laboratory tests, and his results were within the normal range.

The doctors did not provide a diagnosis that could explain what had happened. They said that changes in mood and demeanor could be a symptom of bipolar disorder. They prescribed him some pills and agreed to follow up with him.

As time went by, the whispering of the neighbors escalated because his attitude changed continuously and abruptly. The drugs that he had been taking didn’t seem to be having the desired effect.

“Ada, don’t go to the doctor anymore. Let’s find a remedy somewhere else. You’ve taken him three times and nothing has happened. I certainly don’t believe in witches, my friend, but one can never be too careful…” said one of the neighbors to my grandmother.

My grandparents had been born in Rio Arenas, a town near Cumaná, and like all the locals, she was superstitious. They decided to take Raúl to some witch doctors in the city of Maturín, in the state of Monagas. They also went to the towns of Cumanacoa and Marigüitar, in the state of Sucre. For three years, they visited one witch doctor after another.

But, as I was told, my uncle didn’t stop screaming and his bitterness did not subside. He could seem joyful, but not for long. He would turn violent from time to time, and there was no other choice but to confront him strongly. The conclusion, after many visits to the witch doctors, was that an evil spell had been cast on him through that rum. He was recommended natural remedies and herbal baths.

Raúl agreed to follow the recommendations and, with the family’s help, he seemed to have recovered four months later. He was calm. He was again the person he used to be before that night: he would engage in conversations, he would run errands, he conveyed serenity.

Nevertheless, terror returned upon his father’s death in 1985.

Nevertheless, terror returned upon his father’s death in 1985.

My uncle was already 32. I wasn’t even born. I am told that, during the funeral, he remained silent, deep in his thoughts, staring at the flowers and the casket. He never cried. Tears would well up in his red eyes, but they would stay there.

The day of the funeral, he was in the thick of an emotional shock. He relapsed. They had to admit him to the Antonio Patricio de Alcalá University Hospital, where he was assessed, injected with sedatives, and placed under a strict treatment regimen. And this time they had an accurate diagnosis: he had schizophrenia.

I was born in September of 1997. My uncle thought I was a doll, so my mother had to be vigilant in order to protect me from him. As I got older, I kept some distance myself, but the family was always there to protect me.

Mom knew that Raúl scared me. She would explain to me that he was a psychiatric patient, but I remember she did so hesitantly; she couldn’t find the right words for a seven-year-old to understand that his uncle was doing weird things because of his mental illness.

“José Luis, don’t go anywhere near him because he’s a lunatic.”

I remember the constant warnings from my relatives. I was in second grade in elementary school and I would wonder: “Could it be that he’s an astronaut? Where is his suit? Wow! What if I ask him to take me to the moon on his next trip? What would his ship look like?”

My thoughts would be ruined as soon as I saw Pancholón, as we called him, running aimlessly around the house, trying to open the gate to get out and greet people, or hitting his head against the wall like a nail-burying hammer. He would sit on the glass tables until they were broken. When he yelled out names and cursed, he felt free. He lived in his own world.

He would end his lunatic hours by excreting urine and feces. The living room was his bathroom, the porch was his bedroom, and the patio was his dining room. The kitchen was the only place he didn’t mix up because he loved to eat.

When he was hungry, he would scream at the top of his lungs: “Laura, I want food!”

Laura was his sister. She was cheerful and loved to joke around, which helped her cope with the life she had been dealt, having to take care of my uncle. She worked at the municipal market selling meals to truckers. Raúl would sometimes snatch ingredients from her and eat the arepas her customers had ordered. He would hide onions and tomatoes in his pants pockets and then eat them like fruit as he arrived on the patio. He finished his snack with a sip of bleach or floor cleaner.

Every time my family forgot to remove the bottles of cleaning products from the patio, they knew they would immediately have to ready two glasses of milk, for it is said that milk neutralizes the effects of poison.

At home, they learned to control his bouts of schizophrenia by giving him drops, pills, and injections. I heard the names of the drugs so much that I knew them all: Mellaril, Sinogan, Akineton, Haldol, Neuleptil. But they were less and less effective on him. And, although the doctors’ instructions were followed as given, Raúl couldn’t even sleep.

We looked like zombies. Nobody could get any rest.

One day, in 2005, my uncle was rocking in the rocking chair in the living room, banging his head. It was lunchtime and they called him to eat, but he didn’t get up. When they went to the living room to hand him his plate of food, he hurled it through the room. It landed on the floor. So, he got up and grabbed the broom, which he wielded as a weapon, threatening everybody, instead of using it to clean up the mess.

He was running wild all around the house. He was enraged… again. He would hit his head with whatever he could find in his path. We went back to the first chapter of his lunatic story. Everybody was distraught, wondering what to do, throwing their hands up in the air because there was only half a tablet of Sinogan left and there was no Akinaton in the house either. It was a weekend. In Venezuela, restrictions had been applied on medications containing addictive substances.

They needed a doctor, a nurse, a paramedic, someone who knew how to control him. They took a taxi and drove him to the Antonio Patricio de Alcalá University Hospital. They went to the top floor, which is where the mentally ill receive treatment. The place smelled of rust and rotten blood.

“Good afternoon. My brother has had several crises since early this morning. We don’t know what to do,” said my mom, worried and upset.

“Well, take him back with you, ma’am; for now, we are out of supplies.”

She was outraged by the response from the medical staff, and she decided she would threaten to leave him there.

“How can you ask me to take him with me? Isn’t this place supposed to guarantee him attention? If you have no medicines here, just imagine the picture back home. Some doctors love to break their oath. If you don’t take him in, I’ll leave him here just the same.”

And that’s what she did.

Raúl was left wandering around the tenth floor until the staff personally experienced what his family went through every day at the house. So, they tied him to a stretcher and gave him Haldol to control his psychotic disorder.

The psychiatrist who treated him spoke to the family. She recommended adapting spaces in the home so that my uncle, Mr. Monster, could be sent back. She took the opportunity to warn that if the disorder continued to progress, he would have to be admitted to a psychiatric ward.

At home, they decided to weld bars onto the windows of one room and around the patio, in an effort to keep him in one area of the house. But the forced solution made the situation worse, as one would expect. Raúl would bang on the bars like a prisoner in despair. He would stretch his arms to grab anyone who came close. He would curse like hell. He needed to be admitted to a ward. There was no other choice.

And so began the search for a place that would be fit for schizophrenics, but all the mental institutions were full. They needed to secure his well-being without throwing him into oblivion. Some friends from Caracas, seeing that the family was tired and had virtually no hope, recommended my aunts take him to a facility in the state of Miranda, more than 330 kilometers from Cumaná. There—they were told—he could probably be taken in. And so he was.

In 2006, the sound of that alarm that used to wake me up to frightening mornings stopped altogether.

One morning, a truck parked outside my house to pick up my Aunt Laura’s furniture. She was moving to a residence in Miranda to be near Raúl. He was to be admitted to the La Paz Mental Sanatorium, in the Carrizal municipality. In that place, he made friends and found medication, and was treated by medical staff that was willing to look after him. My other aunts from Caracas visited him every Sunday. Sundays were for talking, laughing, singing, and eating lots of food. His life took a turn for the better, just like ours. He was glowing. We could finally rest.

Those of us who stayed in Cumaná would visit him occasionally. Not as much as we would have wanted to, because my mother worked a lot and she had neither the time nor the money to go that often.

I got a chance to see him. A strange sensation ran through my body. Fear escorted me to the doors of the psychiatric ward. But then it left and let me share with him. The place was a big house with gardens. The patients stared at me. Some of them even approached me and told me about their lives. My uncle didn’t remember my name, but he gave me his blessing when I said goodbye, as he always did.

That was the last time I saw him.

Things in the sanatorium began to deteriorate, as funding was scarce. It was a state-funded institution. They had to send several patients to wards located in other regions of the country. Raúl was taken to the Buena Vista Mental Sanatorium in Macaira, state of Guárico, more than 168 kilometers from Miranda.

On November 10, 2016, Laura got a call from said rural psychiatric facility. Without much ado, she was told that her brother had died, allegedly from pneumonia. On that same day, she traveled to the outskirts of Altagracia de Orituco on ruined roads. She crossed rivers and streams until she arrived at her destination. Upon entering the place, she was greeted with her brother’s decomposing body.

His death has been an enigma.

No one knows for sure the exact date when he passed away, or how. In the course of time, we learned that Macaira’s rural psychiatric hospital had become an epicenter of death. Other ward patients had lost their lives, like Raúl. Some families didn’t even get to bury their loved ones for, when they arrived at the place, they were told that he or she had been taken to a mass grave.

The night when my uncle had that glass of rum changed his life… and ours. We lost him back then, somehow. Who would have thought that, in the interest of everyone’s wellbeing, we would lose him again? Only this time, we lost him forever.

Translated by Yazmine Livinalli

This story was produced within the framework of the La Vida de Nos Itinerante Universitaria program, which offers workshops on real-life storytelling for university students and professors from sixteen Social Communication schools in seven Venezuelan states.