In Jazmina Barrera’s work there are weavings, notebooks, threads, mysteries, crossovers. Recipient of a fellowship from the Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas and the Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, winner of the Latin American Voices prize, and cofounder of the publishing house Ediciones Antílope, Barrera establishes a prolific dialogue with literary traditions, amplifying the voices of writers and artists with whom she shares preoccupations and questions.

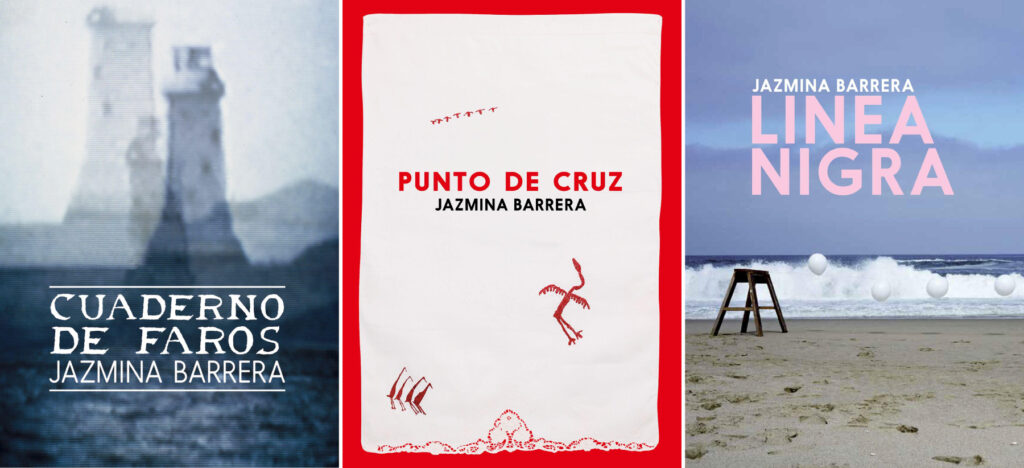

In her books Cuerpo extraño (Literal Publishing, 2013), Cuaderno de faros (Tierra Adentro, 2017), Línea nigra (Almadía, 2021), and Punto de cruz (Almadía, 2021), there converge themes such as motherhood, bodies, loneliness, family, isolation and, among them all, many questions. Through diaries and fragments—which she considers versatile literary tools—and explorations on themes that preoccupy her, Jazmina Barrera has built a body of work that today is read in five languages and with great attention.

Here we converse with the author about her work, the points of convergence between her books, and the current state of Latin American literature.

Juan Camilo Rincón & Natalia Consuegra: Regarding some of your works, you mention an intersection that transcends genre, that what some call a novel you consider an essay, uncoupled from any academic connotations or categorial assertions…

Jazmina Barrera: I think what I associate immediately with the essay is freedom. I studied in a primary school outside of Mexico City where they used a system called Freinet. One of the elements of that system is that, every so often, the teacher asked us to do a free write; they didn’t say a story, an essay… They said: a free write. Then we printed those texts, because we had little movable-type printers, and we made books. I remember perfectly the first text of mine that was printed and the excitement of being able to share my ideas, the collective creation, writing as a game, the satisfaction of having a product that emerged from your creativity. That’s when I started to associate writing with pleasure and with freedom, a free write. I feel like I still write free texts. And then in canonical texts, which we have to understand are subjective definitions, classifications that we build out of texts that already exist… From those texts we decide to make classifications. Sometimes it seems like the classifications exist prior to literature, but that’s not true. First come the texts and later the classification, and we have all the freedom possible to write those texts. We can take any literary tool that we associate with the novel, the essay, poetry, they’re there and we can use them. Of course there are certain rules of the game and those are different for every person, in every country, in every culture. For example, the “memoir” genre is something that in Spanish we hardly ever use, maybe we would instead call it “essay.” Our classification of nonfiction is distinct from the English-speaking world’s. So we must understand that these are subjective, cultural classifications and they operate like the rules of a game; for some people they work for their writing or as a departure point for their writing. They don’t work for me; they disorient me, upset me, constrain me. I prefer to think very openly about what I want to say and the literary tools I need to say it. And that, what I do, I call “essay,” because in the essay we find experimentation, process, staging. On the other hand, the word “novel” tells me nothing; it speaks of novelty, something that for me is a value that’s not very useful in writing. And that’s why I think every good book is an essay; on the other hand, a novel… I don’t know.

C. R. & N. C.: Right, to impose a label and a genre ends up limiting the expressive possibilities. It can be complicated for writers as well as for readers…

J.B.: Yes, I think it’s a category that works above all for marketing. It tells the booksellers where to put them and it works for some authors who even play with it, who want to write a novel thinking of the possibilities of the novel, bringing it to its limit, responding to a tradition. There’s lots of people for whom it really does work. It’s like writing a sonnet within those rules; for plenty of people it works and they do it really well, but we can see that for some it doesn’t. As opposed to, for example, visual arts, where alternative media have existed for a long time, or there’s more flexibility for hybridity, the literary industry is still much more ordered according to these canonical genres. If you’re competing for a prize, you have to select a category; if you apply for a master’s program, you have to select a category. And it turns out there’s much more than just that.

C. R. & N. C.: Turning to your books, in Línea nigra you say that one needs a tribe for childrearing, and in Punto de cruz you suggest that weaving is richer as a collective exercise. Is there a dialogue within your body of work? When you reread it, do you find that thread?

J.B.: Well, I don’t read and reread myself; it’s more like I published the book and said goodbye. Unless I have to do it for some specific reason, I prefer not to go back. César Aira said each book is corrected with the next one, and I have faith that that’s true. But I do think there are, of course, like everyone has, manias, obsessions, even defects that repeat from one book to another. I think I can visualize almost all of my books like a collection. I think of it that way because my mother is a painter and my father is a museologist, so the idea of a collection has always been very present in my life; I have a book that is a collection of lighthouses; I have a book that is a collection of stories and visual works that talk about birth, pregnancy, and breastfeeding; I have another book that has a collection of memories, on the one hand, and a sampler of ideas and references that have to do with embroidery in many expressions around the world and in different times. So I think, in that sense, all are books that go from the subjective to the collective, from the personal to the political, and that use fragments also, in different ways and with different pretexts. I’ve always found some motive to make my books fragmentary.

C. R. & N. C.: Among those fragments appears the family. How does that work in and for your writing?

J.B.: Family, in my case, has always been a broad term. I grew up with my mother and my father, but I never had siblings; my cousins are the closest to that. As a girl I was very close with my paternal grandmother, who lived close to my house, and also to my maternal grandmother and grandfather, with whom I spent every weekend. My aunts were very important in my life, my second cousins. It’s an extensive family that has been fundamental in my life, not only in my emotional development, but also in my intellectual development, and now that I have a child it is also a very important part of my support network. Of course, my family also had cats, dogs, friends… I believe in chosen family, and sometimes you can choose within that family that is your biological family, sometimes not. I think family is a very important component of our identity. Its history, its layout, its attitude, its lexicon, as Natalia Ginzburg would say, influence in a determining way the people we are, for better or for worse; often they work as a counter-example. Now that I am a mother, they are also the primary reference point I have for childrearing and caregiving.

C. R. & N. C.: How have you addressed that topic in your literature?

J.B.: In my work, family is above all a group of stories, the ones I feel closest to and that touch me emotionally the most directly, and that have influenced the people around me and who I am. I use those stories as literary material, and often I put them into dialogue with other things, with the outside world, with other stories, other families and lots of other ideas. I go back to Natalia Ginzburg with her book Léxico familiar, which to me is a wonderful example of what you can do with family in literature, how family creates our first language. For example, to say we speak the same language is always an exaggeration, because there are always phrases we don’t understand, words we don’t know, and with family we share more words, more sayings, more local jokes, that maybe mean something different to us than to the rest of the world.

C. R. & N. C.: Do you think we have achieved a fluid dialogue between our literatures, at least in Latin America?

J.B.: I think we are more and more independent from Spain, although still the two largest Spanish-language publishing houses have their headquarters there. This fact, clearly, determines to a large extent what we read and how we read. I think the hope here is in independent presses, because it seems to me that they are the ones who have made sure to investigate, read, look for what’s happening in other countries, make rights trades, co-editions, editorial lines that very explicitly look for a Latin American catalogue, like the case of Laguna in Colombia, for example. Although there are initiatives at large presses as well: at Random House there’s Mapa de Lenguas, which possibly brings more authors to new places, but I think it’s still lacking.

C. R. & N. C.: How do you read literature that addresses violence? Someone spoke about the importance of those books that now call things by their names (in the case of femicides, for example). Are we facing new narrative forms?

J.B.: I don’t know. The dilemmas are still the same as always. Whether or not to aestheticize violence, whether to address it in a literal, crude, and stark manner or in a more indirect and subtle manner… I think the aesthetic and ethical dilemmas are still the same. Possibly, as we were saying, women have more freedom to write about these topics than they had before… But still, some of the books I like most lately are not that far from what Faulkner would do. To talk about novelty in literature is very complicated for me because there are things that come and go. We really feed on what existed in the past, and I think, in the case of violence, there is a new vocabulary to talk about it, but I’m not so sure that literature in particular has a direct effect. I think language that comes from academia and the social sciences, in part, is very useful and indispensable to name things we didn’t name before. Nevertheless, I also think that language sometimes alienates, intimidates, complicates, and confuses a lot of people. I, at least, when I write, always try to avoid that vocabulary, because I think doing that allows me to reach more people. I think that has been an error of the left in recent times: maybe we stay too much in our own world and we assume everyone talks like we do, so it becomes hard for us to open up, to reach other audiences and convince more people of the things of which they still need to be convinced.

Translated by Madeleine Arenivar

Photo: Mexican writer Jazmina Barrera.

|

|

Juan Camilo Rincón is a writer, journalist, and cultural researcher focusing on Hispano-American literature. He earend his Master’s in Literary Studies from the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and is a former grantee of FONCA (Mexico). He is the author of Ser colombiano es un acto de fe: Historias de Jorge Luis Borges y Colombia, Viaje al corazón de Cortázar, Nuestra memoria es para siempre, and Colombia y México: entre la sangre y la palabra. He has written on cultural topics for outlets in Latin America and Spain, and has been a guest author at international book fairs in Bogotá, Culiacán, Guadalajara, Guayaquil, Havana, and Pachuca. (Photo: Jimena Cortés) |

|

|

Natalia Consuegra is a cultural journalist. She writes on literary topics for outlets in Latin America and Spain. She also works as a proofreader and copy editor (APA style and RAE guidelines). (Photo: Walter Gómez Urrego) |