Alberto Chimal: Manos de Lumbre

Of the stories in Manos de lumbre, Jean-Paul Sartre’s words ring true: “There is no need for red-hot pokers. Hell is other people!” A writer who practices literary plagiarism, an obsessive woman buried under misunderstood motherhood and a sick woman facing the trance of choosing figure among the characters of Alberto Chimal. They live with their own hell, dissimulation, manipulation and uncertainty. Chimal ignites a prose that emphasizes the nuances of fantasy, that always explores limits. This literature mixes gambling with hypnosis, drawing in the reader—and possibly burning them. In his words, he seeks out a fantastic imagination that has the virtue of observing objective reality, emphasizing many aspects of existence that, perhaps, could not have been highlighted in other writing styles.

Of the stories in Manos de lumbre, Jean-Paul Sartre’s words ring true: “There is no need for red-hot pokers. Hell is other people!” A writer who practices literary plagiarism, an obsessive woman buried under misunderstood motherhood and a sick woman facing the trance of choosing figure among the characters of Alberto Chimal. They live with their own hell, dissimulation, manipulation and uncertainty. Chimal ignites a prose that emphasizes the nuances of fantasy, that always explores limits. This literature mixes gambling with hypnosis, drawing in the reader—and possibly burning them. In his words, he seeks out a fantastic imagination that has the virtue of observing objective reality, emphasizing many aspects of existence that, perhaps, could not have been highlighted in other writing styles.

.

.

.

.

Ángel Arellano (Coordinator): Florecer lejos de casa, testimonios de la diáspora venezolana

Florecer lejos de casa, testimonios de la diáspora venezolana narrates the true stories of fourteen journalists and writers that had to emigrate from Venezuela due to the social, economic, and political crisis. The severe humanitarian crisis that Venezuelans live has caused millions of people to cross borders in search of opportunities for them and their families in other corners of the world. Away from their homes and their customs, they are leaving behind their life in Venezuela to venture into unknown cities and towns that represent living without scarcity of resources and dramatically high rates of violence. By reading their experiences, the reader can observe how Venezuelans emigrate in terrible conditions, and how the continent is facing a humanitarian disaster comparable with the European refugee crisis.

Florecer lejos de casa, testimonios de la diáspora venezolana narrates the true stories of fourteen journalists and writers that had to emigrate from Venezuela due to the social, economic, and political crisis. The severe humanitarian crisis that Venezuelans live has caused millions of people to cross borders in search of opportunities for them and their families in other corners of the world. Away from their homes and their customs, they are leaving behind their life in Venezuela to venture into unknown cities and towns that represent living without scarcity of resources and dramatically high rates of violence. By reading their experiences, the reader can observe how Venezuelans emigrate in terrible conditions, and how the continent is facing a humanitarian disaster comparable with the European refugee crisis.

.

.

.

.

Emmanuel Carrère: Yo estoy vivo y vosotros estáis muertos. Un viaje en la mente de Philip K. Dick

Story-teller, visionary, genius, prophet, wacko, phony, enlightened, psychotic, radical, drug-addicted, mystic, esoteric, paranoid… Who was Philip K. Dick? To begin with, one of the most innovative, ambitious and powerful science fiction writers of the second half of the 20th century. We are hardly limited to that; his influence extends far beyond the genre. His literary relevance lies in the ability to anticipate disturbing aspects of the modern world and the exploration of issues of great importance: the control of individuals by power, alternative dimensions, human limits, and sensory empowerment through the use of psychotropic substances…

Story-teller, visionary, genius, prophet, wacko, phony, enlightened, psychotic, radical, drug-addicted, mystic, esoteric, paranoid… Who was Philip K. Dick? To begin with, one of the most innovative, ambitious and powerful science fiction writers of the second half of the 20th century. We are hardly limited to that; his influence extends far beyond the genre. His literary relevance lies in the ability to anticipate disturbing aspects of the modern world and the exploration of issues of great importance: the control of individuals by power, alternative dimensions, human limits, and sensory empowerment through the use of psychotropic substances…

.

.

.

.

Ernesto Pérez Zúñiga: Escarcha

Escarcha is a bildungsroman in the Granada of political transition, where it discusses the purity of children and how it is lost in the world of adults. It takes a choral perspective: multiple characters are driven by their own worries, just like the music teacher that is committed to stealing the purity from his students before they become adults. Monte will have to learn that everything, even that which appears to be most beautiful, can be a source of pain. He’ll also learn that there is a hidden treasure that can be discovered with detachment from imposed identity, a glow whose fullness will not be stolen. Written with intensity and harmony, Escarcha is a generational novel. A naked portrait that is extraordinarily sensitive about the experience of living and the journey of the human soul towards reconciliation with itself.

Escarcha is a bildungsroman in the Granada of political transition, where it discusses the purity of children and how it is lost in the world of adults. It takes a choral perspective: multiple characters are driven by their own worries, just like the music teacher that is committed to stealing the purity from his students before they become adults. Monte will have to learn that everything, even that which appears to be most beautiful, can be a source of pain. He’ll also learn that there is a hidden treasure that can be discovered with detachment from imposed identity, a glow whose fullness will not be stolen. Written with intensity and harmony, Escarcha is a generational novel. A naked portrait that is extraordinarily sensitive about the experience of living and the journey of the human soul towards reconciliation with itself.

.

.

.

.

Horacio Castellanos Moya: Moronga

In this novel, José Zeledón, a quiet and sullen man, goes through life haunted by his violent past. Fleeing El Salvador after the civil war and with a new identity, he has managed to remain unnoticed for years in the United States. Now, he must leave Texas to start again in Wisconsin. Other characters of Moronga, Zeledón and Aragón, are survivors of horror: paranoid beings in a constant state of alert. There, stories are told that remember the past, the guerilla, and the narco, all whie the author establishes connections with violence, ultimately reaching a shocking end in which all paths unite. Castellanos Moya is one of the most assertive and unique authors of his generation, and the only that, according to Roberto Bolaño, has been able to narrate “the horror, the secret Vietnam that during a long time was Latin America”.

In this novel, José Zeledón, a quiet and sullen man, goes through life haunted by his violent past. Fleeing El Salvador after the civil war and with a new identity, he has managed to remain unnoticed for years in the United States. Now, he must leave Texas to start again in Wisconsin. Other characters of Moronga, Zeledón and Aragón, are survivors of horror: paranoid beings in a constant state of alert. There, stories are told that remember the past, the guerilla, and the narco, all whie the author establishes connections with violence, ultimately reaching a shocking end in which all paths unite. Castellanos Moya is one of the most assertive and unique authors of his generation, and the only that, according to Roberto Bolaño, has been able to narrate “the horror, the secret Vietnam that during a long time was Latin America”.

.

.

.

.

Isabel Allende: Más allá del Invierno

Isabel Allende begins with the celebrated quote from Albert Camus: “In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.” This urges along a plot that, with a thriller’s rhythm, presents the human geography of characters that are characteristic of the today’s America. A Chilean woman, a young illegal Guatemalan girl, and an older North American Jew survive a terrible snowstorm that occurs in the middle of winter in New York. They end up learning that, beyond the winter, there lies room for unexpected love and for an invincible summer that offer life when they least expect it. A decidedly current piece, it addresses the reality of immigration and identity through characters that find hope in love and second chances.

Isabel Allende begins with the celebrated quote from Albert Camus: “In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer.” This urges along a plot that, with a thriller’s rhythm, presents the human geography of characters that are characteristic of the today’s America. A Chilean woman, a young illegal Guatemalan girl, and an older North American Jew survive a terrible snowstorm that occurs in the middle of winter in New York. They end up learning that, beyond the winter, there lies room for unexpected love and for an invincible summer that offer life when they least expect it. A decidedly current piece, it addresses the reality of immigration and identity through characters that find hope in love and second chances.

.

.

.

.

María José Caro: ¿Qué tengo de malo?

The storybook ¿Qué tengo de malo? by María José Caro, portrays the coming of age of a middle-class girl in Lima named Macarena during the nineties. Macarena doesn’t really know who she is. She can be the insecure student that begins school in hopes of finding a sense of belonging; the daughter of separated parents that doesn’t know how to behave at Sunday dinner; the sister of a boy who has the same problems she does with processing trouble at home; the girl that doesn’t know the trending dance moves at parties; or the teenager that believes that love is recognizing one’s self in the soul of another. María José Caro explains that to write these stories she looked model authors like the Canadian Alice Munro and the American Lorrie Moore. From Moore, she includes one quote as an epigraph on her book.

The storybook ¿Qué tengo de malo? by María José Caro, portrays the coming of age of a middle-class girl in Lima named Macarena during the nineties. Macarena doesn’t really know who she is. She can be the insecure student that begins school in hopes of finding a sense of belonging; the daughter of separated parents that doesn’t know how to behave at Sunday dinner; the sister of a boy who has the same problems she does with processing trouble at home; the girl that doesn’t know the trending dance moves at parties; or the teenager that believes that love is recognizing one’s self in the soul of another. María José Caro explains that to write these stories she looked model authors like the Canadian Alice Munro and the American Lorrie Moore. From Moore, she includes one quote as an epigraph on her book.

.

.

.

.

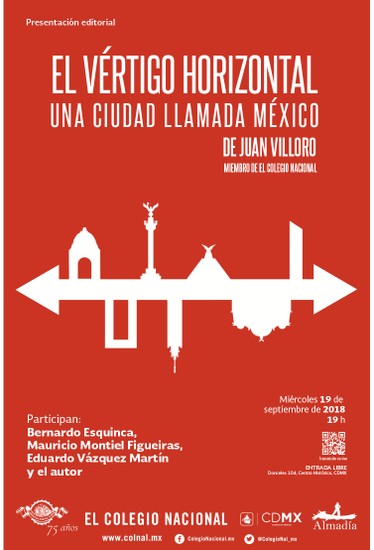

Juan Villoro: El vértigo horizontal. Una ciudad llamada México.

El vértigo horizontal. Una ciudad llamada México, brings together over 40 chronicles about the city written during the last two decades. With an attentive look and a firm hand, Villoro emerges as a journalist, a passer-by, a buyer of pens, a nostalgic adult, a responsible father, and an emergency brigade member, offering us a testimony of the many adventures that the city holds for every one of its inhabitants. Whether from experience or through listening and researching the realities of others, Juan Villoro composes a great fresco of the endearing and eternal chaos that makes up the country’s capital. Accompanying the chronicles, there are inspirational photos taken by Dr. Alderete, Yolanda Andrade, Paolo Gasparini, Pablo Lopez Luz, Sonia Madrigal, and others.

El vértigo horizontal. Una ciudad llamada México, brings together over 40 chronicles about the city written during the last two decades. With an attentive look and a firm hand, Villoro emerges as a journalist, a passer-by, a buyer of pens, a nostalgic adult, a responsible father, and an emergency brigade member, offering us a testimony of the many adventures that the city holds for every one of its inhabitants. Whether from experience or through listening and researching the realities of others, Juan Villoro composes a great fresco of the endearing and eternal chaos that makes up the country’s capital. Accompanying the chronicles, there are inspirational photos taken by Dr. Alderete, Yolanda Andrade, Paolo Gasparini, Pablo Lopez Luz, Sonia Madrigal, and others.

.

.

.

.

María Gainza: El nervio óptico

El nervio óptico is a unique and fascinating story that has been termed unclassifiable as to the genre that it represents. In the piece, life and art intertwine. It contains eleven parts, eleven chapters of a novel that tells a personal and familiar story; nevertheless, it can also be read like eleven stories, or like eleven incursions in the history of painting. Gainza, who has been both an art curator and critic, narrates a transitory space between the museums of her native city, Buenos Aires, where the paintings hang like galleries of diverse lives. “In the distance there is something that you think is beautiful, something that charms you; everything goes in art, and the variables that modify this perception, can be and often are insignificant,” the narrator explains, in the context of a novel where art is bound with fiction.

El nervio óptico is a unique and fascinating story that has been termed unclassifiable as to the genre that it represents. In the piece, life and art intertwine. It contains eleven parts, eleven chapters of a novel that tells a personal and familiar story; nevertheless, it can also be read like eleven stories, or like eleven incursions in the history of painting. Gainza, who has been both an art curator and critic, narrates a transitory space between the museums of her native city, Buenos Aires, where the paintings hang like galleries of diverse lives. “In the distance there is something that you think is beautiful, something that charms you; everything goes in art, and the variables that modify this perception, can be and often are insignificant,” the narrator explains, in the context of a novel where art is bound with fiction.

.

.

.

.

Octavio Armand: Escribir es cubrir (Pulpo de ensayos)

According to Rafael Castillo Zapata, the powerful yet playful temperament of Octavio Armand’s style does not allow the grace of a resonant correspondence that emerges from his writing to pass without being caught in flight. The possibility of establishing links between similar words never escapes him. Hence his taste for analogies and etymologies, mirrors and echoes. Escribir es cubrir is an amazing and dizzying display of the magical powers of language that Armand, a cunning magician, declaims and exclaims between passes and steps of alliteration and paronomasias in a festive, resonant mosaic where ideas arise like lightning. In these new and old pages there is once again, altogether the same and the other, Octavio Armand explaining and contradicting himself, like a derviche in his always vertiginous verbal dance.

According to Rafael Castillo Zapata, the powerful yet playful temperament of Octavio Armand’s style does not allow the grace of a resonant correspondence that emerges from his writing to pass without being caught in flight. The possibility of establishing links between similar words never escapes him. Hence his taste for analogies and etymologies, mirrors and echoes. Escribir es cubrir is an amazing and dizzying display of the magical powers of language that Armand, a cunning magician, declaims and exclaims between passes and steps of alliteration and paronomasias in a festive, resonant mosaic where ideas arise like lightning. In these new and old pages there is once again, altogether the same and the other, Octavio Armand explaining and contradicting himself, like a derviche in his always vertiginous verbal dance.

.

.

.

.

Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles: Blue Label

Recently, the English version of Blue Label, written by Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles and translated by Paul Filev was published in New York. As Carmen Boullosa points out: “It has a piece of Scheherazade, two fragments of Boccaccio, a touch of Bolaño and a hint of bitterness. Blue Label is intoxicating, hilarious and the best novel about the calamity that defines Venezuela today.” With an unvarnished fluidity, which suggests Jack Kerouac, and a list of songs ranging from REM to Bob Dylan, from El Canto del Loco to Shakira, Blue Label is a daring, dark novel with a final punch at the end. It is the first award-winning book by a writer who has consolidated his reputation as one of the leading young Latin American voices.

Recently, the English version of Blue Label, written by Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles and translated by Paul Filev was published in New York. As Carmen Boullosa points out: “It has a piece of Scheherazade, two fragments of Boccaccio, a touch of Bolaño and a hint of bitterness. Blue Label is intoxicating, hilarious and the best novel about the calamity that defines Venezuela today.” With an unvarnished fluidity, which suggests Jack Kerouac, and a list of songs ranging from REM to Bob Dylan, from El Canto del Loco to Shakira, Blue Label is a daring, dark novel with a final punch at the end. It is the first award-winning book by a writer who has consolidated his reputation as one of the leading young Latin American voices.

.

.

.

.

Rubén Medina (Editor): Perros habitados por las voces del desierto. El infrearrealismo en dos siglos.

The option of infra-realism always meant living in the time in which we must live (with its undeniable circumstances) or in the time we choose, opposed to the homogenization of time. Barely two or three years before the appearance of the infra-realist movement, Deleuze and Guattari would call this condition of capitalist society schizophrenia, a daily conflict within individuals between the desire for autonomy and the compulsive impulse of consumerism. Infra-realism does not represent a school or literary tendency seeking out accommodation; it is a disruptive movement. That is where our unprecedented and daily reality is found, multi-centric and capriciously non-linear.

The option of infra-realism always meant living in the time in which we must live (with its undeniable circumstances) or in the time we choose, opposed to the homogenization of time. Barely two or three years before the appearance of the infra-realist movement, Deleuze and Guattari would call this condition of capitalist society schizophrenia, a daily conflict within individuals between the desire for autonomy and the compulsive impulse of consumerism. Infra-realism does not represent a school or literary tendency seeking out accommodation; it is a disruptive movement. That is where our unprecedented and daily reality is found, multi-centric and capriciously non-linear.

.

.

.

.

Remedios Zafra: El entusiasmo

El entusiasmo is a generational novel about those who were born at the end of the twentieth century. They grew up without an epic (but with expectations) until crisis created a new scenario that has become structural: instability and disappointment. This work portrays the forms of instability in the small details, intertwining ethnographic description with a literary one. It does so with unexpected characters, characteristic of a novel, who play the role of reflecting the complexity and contradictions of our time. The normalization of different forms of precariousness in the digital era is supported further by online lives. Time is linked with the web and with those who “live” online. An “us” emerges as the great creative product of today, at risk of losing that which is most valuable: the liberty that transforms human creativity into something transformative itself.

El entusiasmo is a generational novel about those who were born at the end of the twentieth century. They grew up without an epic (but with expectations) until crisis created a new scenario that has become structural: instability and disappointment. This work portrays the forms of instability in the small details, intertwining ethnographic description with a literary one. It does so with unexpected characters, characteristic of a novel, who play the role of reflecting the complexity and contradictions of our time. The normalization of different forms of precariousness in the digital era is supported further by online lives. Time is linked with the web and with those who “live” online. An “us” emerges as the great creative product of today, at risk of losing that which is most valuable: the liberty that transforms human creativity into something transformative itself.

.

.

.

.

Rafael Castillo Zapata: El semiólogo salvaje. Roland Barthes y la semiología

Alejandro Sebastiani Verdezza points out that there is a deep harmony between the essays of Rafael Castillo Zapata and his diaries, his reading “notes,” and his long strings of fragments. Sometimes they are classes, sometimes collages, and sometimes a mixture of both – an inquiry about Roland Barthes. This outlook touches upon and writes about its “object” for pleasure. Everything speaks for the wild semiologist: the menu of a restaurant, the advertisement of a store, the reread and marked page, the clothes and photographs, the melodies. Thus, Castillo Zapata assumes that knowledge can also be dramatized and put in doubt (it is recognized in what it looks at, it makes it its own) with his usual tone, full of ramifications, reflections of “amphibological spirit” within a “critical attitude based on the paradox”, always ready to enter the crisscrossed game of abductions and resonance.

Alejandro Sebastiani Verdezza points out that there is a deep harmony between the essays of Rafael Castillo Zapata and his diaries, his reading “notes,” and his long strings of fragments. Sometimes they are classes, sometimes collages, and sometimes a mixture of both – an inquiry about Roland Barthes. This outlook touches upon and writes about its “object” for pleasure. Everything speaks for the wild semiologist: the menu of a restaurant, the advertisement of a store, the reread and marked page, the clothes and photographs, the melodies. Thus, Castillo Zapata assumes that knowledge can also be dramatized and put in doubt (it is recognized in what it looks at, it makes it its own) with his usual tone, full of ramifications, reflections of “amphibological spirit” within a “critical attitude based on the paradox”, always ready to enter the crisscrossed game of abductions and resonance.

.

.

.

.

Samanta Schweblin: Kentukis

A new novel by prestigious Argentine author Samanta Schweblin reveals the most disturbing side of new technologies… It almost always starts in homes. Thousands of cases have already been registered in Vancouver, Hong Kong, Tel Aviv, Barcelona, Oaxaca … and it is rapidly spreading to all corners of the world. They are not pets, ghosts, or robots; they are real citizens. The problem is—it’s been reported in the news and shared all over social media—that a person living in Berlin should not be able to roam around freely in the living room of someone living in Sydney, nor should a person living in Bangkok be able to have breakfast with your children in your apartment in Buenos Aires—especially when the people we let into our homes are complete strangers.

A new novel by prestigious Argentine author Samanta Schweblin reveals the most disturbing side of new technologies… It almost always starts in homes. Thousands of cases have already been registered in Vancouver, Hong Kong, Tel Aviv, Barcelona, Oaxaca … and it is rapidly spreading to all corners of the world. They are not pets, ghosts, or robots; they are real citizens. The problem is—it’s been reported in the news and shared all over social media—that a person living in Berlin should not be able to roam around freely in the living room of someone living in Sydney, nor should a person living in Bangkok be able to have breakfast with your children in your apartment in Buenos Aires—especially when the people we let into our homes are complete strangers.

.

.

.

.

David Toscana: The Enlightened Army. Translated by David William Foster.

“The Enlightened Army tells the story of Ignacio Matus, a public school history teacher in Monterrey, Mexico, who gets fired because of his patriotic rantings about Mexico’s repeated humilliations by the United States. Not only did Mexico’s northern neighbor steal a large swath of the country in the Mexican-American War, but according to Matus, it also denied him Olympic glory. Excluded from the 1924 Olympics, Matus ran his own parallel marathon and beat the time of the American who officially won the bronze medal. After spending decades attempting to vindicate his supposed triumph and claim the medal, Matus seeks an even bigger vindication—he will reconquer Texas for Mexico! Recruiting an army of “los iluminados,” the enlightened ones, Matus sets off on a quest as worthy of Don Quixote as it is doomed.” (University of Texas Press)

“The Enlightened Army tells the story of Ignacio Matus, a public school history teacher in Monterrey, Mexico, who gets fired because of his patriotic rantings about Mexico’s repeated humilliations by the United States. Not only did Mexico’s northern neighbor steal a large swath of the country in the Mexican-American War, but according to Matus, it also denied him Olympic glory. Excluded from the 1924 Olympics, Matus ran his own parallel marathon and beat the time of the American who officially won the bronze medal. After spending decades attempting to vindicate his supposed triumph and claim the medal, Matus seeks an even bigger vindication—he will reconquer Texas for Mexico! Recruiting an army of “los iluminados,” the enlightened ones, Matus sets off on a quest as worthy of Don Quixote as it is doomed.” (University of Texas Press)

.

.

.

.

Armonía Somers: The Naked Woman. Translated by Kit Maude.

“On her thirtieth birthday, Rebeca Linke uproots herself from her well-to-do existence by taking a train into the forest, discarding her clothing, and metaphorically beheading herself. As she wanders the countryside, her surreal presence haunts a nearby village and drives its misogynistic inhabitants to madness. Rebeca’s subversion of the male gaze and ontological awakening leads to devastating consequences within a hostile society, unwilling to let go of its small-mindedness.” (Feminist Press)

“On her thirtieth birthday, Rebeca Linke uproots herself from her well-to-do existence by taking a train into the forest, discarding her clothing, and metaphorically beheading herself. As she wanders the countryside, her surreal presence haunts a nearby village and drives its misogynistic inhabitants to madness. Rebeca’s subversion of the male gaze and ontological awakening leads to devastating consequences within a hostile society, unwilling to let go of its small-mindedness.” (Feminist Press)

.

.

.

.

Hugo García Manríquez: Lo común

The first chapbook from Meldadora, a new press based in Monterrey, Mexico, Lo común is a long, powerful poem, claiming a place in the new panorama of radical poetry alongside Estilo by Dolores Dorantes, Antígona González by Sara Uribe, and Widescreen by Victor Cabrera. According to Inti García Santamaría, “the poetry of Hugo García Manríquez is very probably the most unpredictable and the most indispensable currently coming out of Mexico.”

The first chapbook from Meldadora, a new press based in Monterrey, Mexico, Lo común is a long, powerful poem, claiming a place in the new panorama of radical poetry alongside Estilo by Dolores Dorantes, Antígona González by Sara Uribe, and Widescreen by Victor Cabrera. According to Inti García Santamaría, “the poetry of Hugo García Manríquez is very probably the most unpredictable and the most indispensable currently coming out of Mexico.”

Compiled by Claudia Cavallin

Translated by Juliana Giusti Cavallin

Edited by Michael Redzich