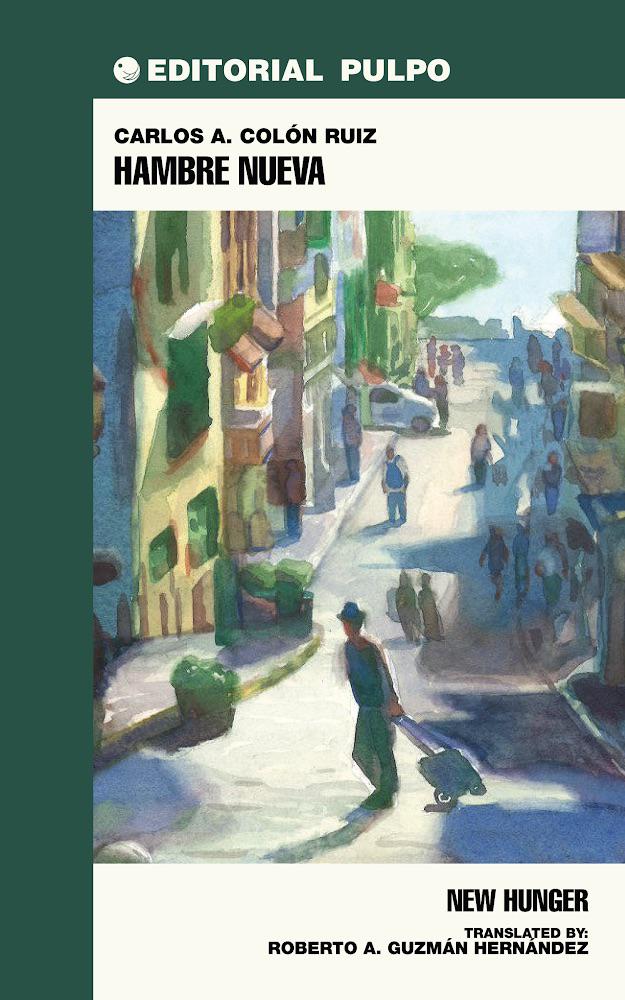

Puerto Rico: Editorial Pulpo. 2023. 76 pages.

Some hold the illusory belief that those who write poetry require “appropriate” places in which to practice their craft—that the poet writes only under “ideal” conditions in physical spaces that lend themselves to creativity. But, in fact, this is a mere fantasy; the reality could not be more different. Poets can, in fact, be insurance agents, taxi drivers, shopkeepers, servers, cleaners, engineers, baristas, and teachers. They can even work at the supermarket.

Some hold the illusory belief that those who write poetry require “appropriate” places in which to practice their craft—that the poet writes only under “ideal” conditions in physical spaces that lend themselves to creativity. But, in fact, this is a mere fantasy; the reality could not be more different. Poets can, in fact, be insurance agents, taxi drivers, shopkeepers, servers, cleaners, engineers, baristas, and teachers. They can even work at the supermarket.

Translated to English by Roberto Guzmán Hernández, Hambre nueva/New Hunger is the third book in the Oleajes/Waves collection. It is a second, extended edition of Hambre nueva (2019), the first book by Puerto Rican poet Carlos A. Colón Ruiz. Hambre nueva/New Hunger approaches everyday themes that seem unimportant, that seem to have been drawn from the most irresolute reality of certain human beings. But it is just there, in its “apparent everydayness,” where the poetry finds its substance, making of this day-to-day existence the poetics that run through the book: “Everything seems to end / leaving us with no final decisions / leaving us in a vacuum / that feeds on our doubt.”

The poet behind these texts leads a run-of-the-mill life, working jobs that seem entirely unpoetic at first sight in spaces that seem to contain no poetry. Perhaps there is truth to the verses cited by Carlos A. Colón Ruiz in one of his poems: “sometimes poetry comes in cans / you just have to get them out of the boxes / arrange them on the shelves / and hope some hungry person comes looking for it.”

Along the same lines, the work routine that does so much to chain us down as individuals is a recurring theme in Hambre nueva. As a reader, I feel the desire, the need of this young Puerto Rican poet to tell the story of this routine, which implies not only the irreducible schedule itself, but also what he observes in this commercial space, a supermarket, where he returns daily to work his shift.

“IN THESE POEMS, THE PRODUCTS IN THE SUPERMARKET COME TO LIFE. THEY MAY BE ON THE SHELVES, BUT THEY APPEAR STRIPPED OF THEIR REAL CONDITION AND IMBUED WITH HUMANITY”

The young Puerto Rican poet knows his surroundings: he smells them, he holds them in his hand, and then he lets them go. He lets them go in phrases, in verses that give us a glimpse of the literary scene of Puerto Rico, his homeland; but the scenes presented in this book also belong to other contexts and other geographies. This leads to an element of discourse between what is displayed on the outside and what is going on within, eventually turning the inhabited (or visited) territory into a set of images that call on us to observe a harsh, complex social landscape.

For this purpose the poet turns, at times, to irony. Or perhaps this is simple poetic honesty; we have no way of knowing. Cities (San Juan, Panama City, and Havana, to name a few), rivers, universities, public transport: all these spaces serve to bolster this literary project. Likewise, the characters who populate these poems demonstrate the hostility and challenge of living in these times when violence and despair seem to be on the daily to-do list.

Carlos A. Colón Ruiz makes use of varied cultural references: music appears in certain verses, like those where he mentions a song by Mumford & Sons, the names of other countries’ coins, and some names from professional wrestling, such as The Undertaker, to mention just one example: “Back then all I wanted was to sing / The Wolf—preferably in a convertible / between Utah and the complexity / of my calmness.”

This voice sees fit to tell us the poet looks at the world and tries to comprehend it, despite feeling like a cliff of shit teetering between the real world and his dreams. This character who traipses between the cans, aisles, and customers of a supermarket ends up being just like that coworker who walks without meaning. Here is a man who watches time pass, and might sometimes seem pessimistic. He is just someone who exposes what he is living through by means of his own personal experience, which is a long way from the “poetic ideal” to which some aspire.

In these poems, the products in the supermarket come to life. They may be on the shelves, but they appear stripped of their real condition and imbued with humanity. Perhaps this is the humanity of the voice that calls on us to observe these objects and these aisles from the plane of our own inner reality. These objects are, in these verses, “in the hands of dreamers and beings / that swap smiles and chocolates / in a San Juan that offers silence and pain / only understood by those / whom the city ignores.”

Hambre nueva refers not only to aisles, products, ignored city-dwellers, and conformist employees. It also puts forth a more intimate poetics, closer to the man and woman who are looking for something of themselves in these verses, even if this is not the reason they are reading. But there can be no doubt that, when we read poetry, nothing is certain: there is only the possibility of an encounter, which might be well received or not. This experience might just end in the desire to keep feeding the appetite of at least one reader.

We can surmise that Hambre nueva is the bringing-together of various appetites: the appetite of the voice behind these poems, the appetite of the characters they follow, the appetite of the reader who succumbs to the poetic act, and even the appetite of the author himself, who offers us so many appetites that we cannot be sure if this hunger is the product of an individual longing or of the vacuum of the world that will someday come and take away our hunger for ideas.