Those who have read Paola Gaviria, known by her pen name Power Paola, probably already know her life story. The new reader who is browsing curiously for the first time through the black and white comics about her family, love, trips, and cities, would need to use a little insight to understand her life. The Colombian-Ecuadorian author and artist used her life as raw material for her debut, the graphic novel entitled Virus Tropical [Tropical virus] (2011). This autobiography was the beginning of Paola’s career in the world of graphic narrative and relates the following story. Paola Andrea Gaviria Silguero was born on June 20, 1977 in Quito, Ecuador. Her parents—a priest and a mystic, both Colombians—had emigrated to the South American city along with their first two daughters shortly before they were surprised by their third pregnancy and the arrival of Paola in their lives. Then, while Paola is growing up and her older sisters experience adolescence, their father leaves the clergy aside, divorces their mother, and returns to his country. Their mother, meanwhile, who has to deal with all of these changes, remains in Ecuador, looking for a job to supplement the family’s income and raise her daughters with the help of a maid until they are old enough to become more or less independent. Virus Tropical doesn’t tell the story as to how Paola Gaviria (the girl) became Power Paola (the artist), but by studying her subjects and techniques, the new reader will learn how the features of her life have ignited an entire career dedicated to comic art.

Virus Tropical is a graphic novel that is constructed by panels organized in chapters. Each of these chapters is in turn a comic story that briefly details a part of the birth or the youth of the artist. These comics, however, do not account for the protagonist’s experience alone, but also aim to include parts of the experience of her parents, sisters, and their maid, the lives that surround and influence Paola’s formation process. This focus on various perspectives that contribute to the personal experience is one of the most characteristic qualities of this debut. We can see this in her art as well, through the lines of the drawings and the way she frames the action, the bubbles of dialogue and narration cartridges, the qualities that make the comic a unique and original means of expression. The artistic style that Power Paola uses in Virus Tropical highlights the way in which her comics communicate the personal experiences that form the core of her theme, always in relation to the spaces in which these experiences unfold.

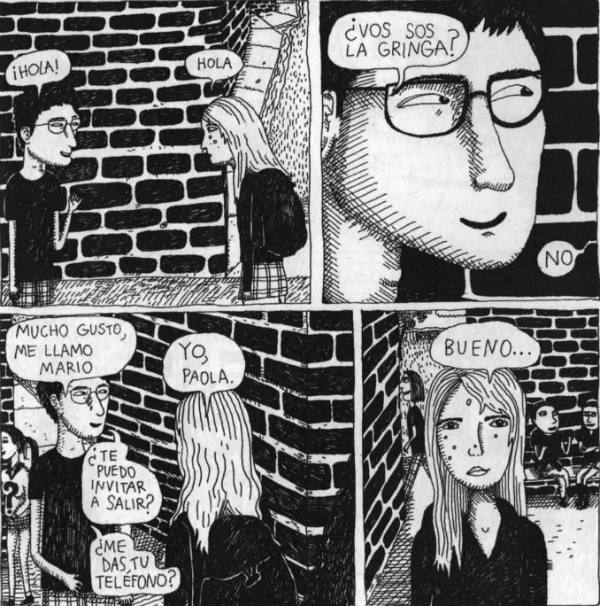

In order to recreate, with meticulous love, the scenarios, places, and times of her life, Power Paola uses a thin line and draws in ink, which she continues to use to this day. With her peculiar artistic style, full of visual information, the panels that frame the action of her comics take advantage of the flat, two-dimensional art of the comic to interweave the characters within their surroundings. In the monochromatic world of Virus Tropical, minimal shadows and plenty of texture emphasize the presence of materials such as wood, textiles, and brick in the background. The materiality of these scenarios attracts the gaze, since these places have the same level of detail as all the other elements of the page. Therefore, in her stories, the houses, streets, schools and buildings of Quito (and then Cali, Colombia) are almost as present as the people who occupy or travel through them, the dialogues they have, and the narrative that provides context. Because the specificity of these environments communicates to the reader the sociocultural sphere that is represented, the graphic novel emphasizes the location of its stories through the visual aspect. Seeing the different spaces through which the little Paola moves allows us to experience an important part of the process that led the girl to become the artist of the autobiography.

In order to recreate, with meticulous love, the scenarios, places, and times of her life, Power Paola uses a thin line and draws in ink, which she continues to use to this day. With her peculiar artistic style, full of visual information, the panels that frame the action of her comics take advantage of the flat, two-dimensional art of the comic to interweave the characters within their surroundings. In the monochromatic world of Virus Tropical, minimal shadows and plenty of texture emphasize the presence of materials such as wood, textiles, and brick in the background. The materiality of these scenarios attracts the gaze, since these places have the same level of detail as all the other elements of the page. Therefore, in her stories, the houses, streets, schools and buildings of Quito (and then Cali, Colombia) are almost as present as the people who occupy or travel through them, the dialogues they have, and the narrative that provides context. Because the specificity of these environments communicates to the reader the sociocultural sphere that is represented, the graphic novel emphasizes the location of its stories through the visual aspect. Seeing the different spaces through which the little Paola moves allows us to experience an important part of the process that led the girl to become the artist of the autobiography.

On the other hand, the small amount of shadows mentioned above can also flatten the reality represented in her art. This is one of the ways in which the design of Power Paola’s characters favors caricature over quasi-photorealism. Another way we can appreciate this feature is in the way she draws bodies. The anatomy of the characters suggests the qualities of a cartoon, where faces are formed by minimal stripes and bodies behave in unreal but expressive ways. When they cry, their eyes are flooded with thick drops; when they shout, their tongues lengthen until they look like the tongue of a serpent. Caricaturizing facial expressions, however, serves to emphasize the emotions and experiences of the characters. In other words, the design of the character’s faces sacrifices the naturalistic simulacrum to take advantage of a sense of intimacy and immediacy to the maximum, attracting readers to the caricature and allowing them to identify with what is supposed to be the experience of a stranger. In this way, Power Paola’s drawings play with the human body, instill the scenes with emotion, and create a bond of emotional nostalgia that communicates the perspective of childhood and domestic surroundings. This perspective allows the reader of Virus Tropical to experience the growth of a girl, as well as the lives that surround her, her family, and her cities. Power Paola’s art therefore transmits the importance of this network of symbiotic interrelationships so that the focus on the personal can resonate with the entirety of the work. This graphic novel expands the genre’s thematic limits, transforming what could be a simple bildungsroman into a reflection on the everyday life of the immigrating Latin American family and the social discourses that establish it.

The graphic novels of Power Paola—read Virus Tropical but also QP (éramos nosotros) [QP (it was us)] (2014), Todo va a estar bien [Everything is going to be fine] (2015) and Nos vamos [We’re leaving] (2016)—share a similar interest in the subtopics of spirituality, class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. However, these topics only reveal the relationship that these concerns bear with the autobiographical information of the plot in its subtext. In Virus, her father’s religion, for example, does not come into direct conflict with her mother’s mysticism, but both elements reiterate the great amount of knowledge and perspectives that could form a personality, suggesting to the reader that the personal experiences of the little Paola are as unique as they are universal. Intertwined with the artistic style, this way of exploring the personal and the everyday in connection with the universal defines a large part of the artist’s corpus. Consequently, the previously mentioned graphic novels sprout like flowers off the tree that is this first book. Taken together, they also reveal a process of artistic evolution that is worth discussing briefly in conjunction with the debut.

The graphic novels of Power Paola—read Virus Tropical but also QP (éramos nosotros) [QP (it was us)] (2014), Todo va a estar bien [Everything is going to be fine] (2015) and Nos vamos [We’re leaving] (2016)—share a similar interest in the subtopics of spirituality, class, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. However, these topics only reveal the relationship that these concerns bear with the autobiographical information of the plot in its subtext. In Virus, her father’s religion, for example, does not come into direct conflict with her mother’s mysticism, but both elements reiterate the great amount of knowledge and perspectives that could form a personality, suggesting to the reader that the personal experiences of the little Paola are as unique as they are universal. Intertwined with the artistic style, this way of exploring the personal and the everyday in connection with the universal defines a large part of the artist’s corpus. Consequently, the previously mentioned graphic novels sprout like flowers off the tree that is this first book. Taken together, they also reveal a process of artistic evolution that is worth discussing briefly in conjunction with the debut.

Firstly, all these texts, including Virus Tropical, have a strong diaristic intention. A large part of the individual comics that fill their respective pages carry the date of the event that is represented (or the date when they were put on paper), the name of the city where it occurred, and/or a subtitle. However, we witness the moments of Paola’s life in and out of order, like the episodes of a TV series which we only watch sporadically. The chronology of these graphic novels is one that changes but is always present. In addition, although these episodes are always guided by the impetus of recording the small interactions that form the day to day, they are rarely geared toward the creation of singular, imposing plots. Like Virus, the rest of the works function as accumulations of formative incidents gathered around a few recurring topics.

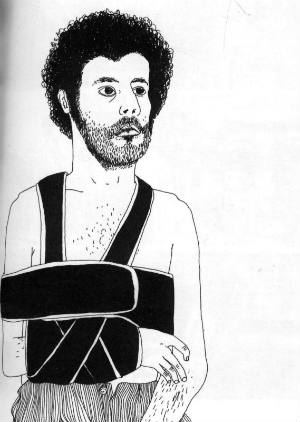

QP (éramos nosotros) cements the style and the format that was inaugurated in Virus. In her second work, Power Paola presents the reader with a diary of her travels and long absences abroad, carried out between 2006 and 2012 with her partner at the time, a man named Quique. This story is of an adult Paola, one who deals with the expectations of an adult relationship and her desire to live an itinerant life. Some of the stories are drawn in color, but the majority are still in the same black and white art as before. Here we also witness a recurring technique in the work of Power Paola, her page-wide portraits. In one of these, Quique appears with his arm in a cast held by a sling. As we see in a previous comic, he hurt himself by drinking and dancing with Paola on one of their many trips together. Looking at the horizon, isolated from the context of the story and its incident, his face also serves to recall the presence of other imbricated experiences in Paola’s life.

QP (éramos nosotros) cements the style and the format that was inaugurated in Virus. In her second work, Power Paola presents the reader with a diary of her travels and long absences abroad, carried out between 2006 and 2012 with her partner at the time, a man named Quique. This story is of an adult Paola, one who deals with the expectations of an adult relationship and her desire to live an itinerant life. Some of the stories are drawn in color, but the majority are still in the same black and white art as before. Here we also witness a recurring technique in the work of Power Paola, her page-wide portraits. In one of these, Quique appears with his arm in a cast held by a sling. As we see in a previous comic, he hurt himself by drinking and dancing with Paola on one of their many trips together. Looking at the horizon, isolated from the context of the story and its incident, his face also serves to recall the presence of other imbricated experiences in Paola’s life.

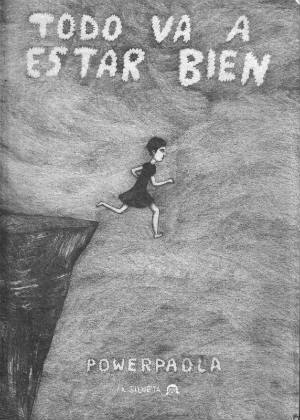

Todo va a estar bien is a book that, although it has a similar theme to the previous one, draws attention for its materiality. The first edition of this graphic novel is created to be touched. The cover is a pencil drawing by the artist in which the caricature of an adult Paola takes a step forward from a cliff, floating in the air just like Wile E. Coyote, the enemy of the Roadrunner, did before falling into a bottomless hole. Around the scene, the sky is all gray—a shadow effect that is achieved by rubbing a pencil on the page—and the letters of the title appear in the form of white clouds, hanging over the top. It is a soft cover book, about the size of a magazine, with legal-sized pages folded in the center and inwards, printed on both sides and attached with glue. These elements turn the graphic novel into an object-book since, due to its cover and the thickness of its pages, it looks like the notebook of an adolescent, a document full of images and secrets close to the heart. Something that would be rolled up and carried in the back pocket of a pair of pants, a backpack full of books, pencils, and pens, or under the arm to be reread a thousand times. Similar to Syllabus (2014) by Lynda Barry or Playground (2013) by Berliac, Todo va a estar bien is Power Paola’s version of stories like the one in the film Y tu mamá también (2001), where the bittersweet experiences of adulthood are mixed with travel and sex in a kind of a visual essay.

Todo va a estar bien is a book that, although it has a similar theme to the previous one, draws attention for its materiality. The first edition of this graphic novel is created to be touched. The cover is a pencil drawing by the artist in which the caricature of an adult Paola takes a step forward from a cliff, floating in the air just like Wile E. Coyote, the enemy of the Roadrunner, did before falling into a bottomless hole. Around the scene, the sky is all gray—a shadow effect that is achieved by rubbing a pencil on the page—and the letters of the title appear in the form of white clouds, hanging over the top. It is a soft cover book, about the size of a magazine, with legal-sized pages folded in the center and inwards, printed on both sides and attached with glue. These elements turn the graphic novel into an object-book since, due to its cover and the thickness of its pages, it looks like the notebook of an adolescent, a document full of images and secrets close to the heart. Something that would be rolled up and carried in the back pocket of a pair of pants, a backpack full of books, pencils, and pens, or under the arm to be reread a thousand times. Similar to Syllabus (2014) by Lynda Barry or Playground (2013) by Berliac, Todo va a estar bien is Power Paola’s version of stories like the one in the film Y tu mamá también (2001), where the bittersweet experiences of adulthood are mixed with travel and sex in a kind of a visual essay.

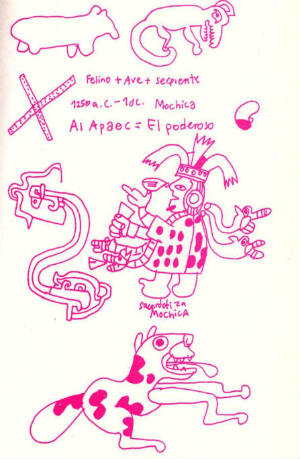

The colors of Nos vamos are the first sign that this book marks a transition in the artist’s comics. Instead of being printed with the black ink of the previous books, the drawings appear in pink, orange, green, and other colors, all in neon tonality. The colors give new life to the subjects explored: trips through Argentina, Bolivia and Peru that not only include the usual conversations that the artist likes to capture, but also give way to notes on historical traces of the Inca and pre-Inca cultures. Although Nos vamos includes comics done as far back as 2013, in this graphic novel we can notice how the artist begins to dismantle the diary format that usually organizes her work. This is because Nos vamos includes even more vignettes that dismantle the narrative, comics that float in the ether and portraits of strangers, scenes that underline the themes of the book or suggest others only to then vanish, windows that become anathemas of the plot organized into acts. Together, both the use of color and the looser, relaxed, or unstitched narrative structure, could be considered indicators of what is to come from Power Paola.

The colors of Nos vamos are the first sign that this book marks a transition in the artist’s comics. Instead of being printed with the black ink of the previous books, the drawings appear in pink, orange, green, and other colors, all in neon tonality. The colors give new life to the subjects explored: trips through Argentina, Bolivia and Peru that not only include the usual conversations that the artist likes to capture, but also give way to notes on historical traces of the Inca and pre-Inca cultures. Although Nos vamos includes comics done as far back as 2013, in this graphic novel we can notice how the artist begins to dismantle the diary format that usually organizes her work. This is because Nos vamos includes even more vignettes that dismantle the narrative, comics that float in the ether and portraits of strangers, scenes that underline the themes of the book or suggest others only to then vanish, windows that become anathemas of the plot organized into acts. Together, both the use of color and the looser, relaxed, or unstitched narrative structure, could be considered indicators of what is to come from Power Paola.

Virus has been published in Colombia, Peru, Brazil, Chile, and Spain, among other countries, has been translated into English and French and now has an adaptation to an animated film that began screening at international festivals in October 2017. Power Paola spends her time publishing more comics, giving workshops on the subject and helping to spread the work of others. If we look at the last five years of her career, she doesn’t show any signs of pausing the continual record of her stay in this world, through her recognizable diary-comics.

Iván Pérez Zayas

Northwestern University