excerpt from the most beautiful place in the world

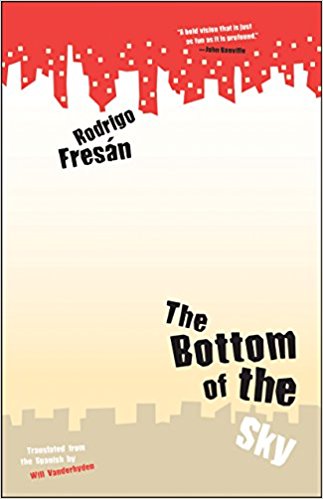

An Excerpt from The Bottom of the Sky

Rodrigo Fresán

Editor’s Note:

Editor’s Note:

Open Letter is a nonprofit literary translation press based at the University of Rochester. The press is dedicated to making world literature available in English and to cultivating an audience for international works of fiction and prose. Latin American Literature Today is excited to partner with Open Letter to present an exclusive excerpt from Rodrigo Fresán’s The Bottom of the Sky, translated from the Spanish by Will Vanderhyden and set to be released in May 2018. LALT extends a special thank you to Chad W. Post of Open Letter for making this collaboration possible.

III

THE OTHER PLANET

And so, sometimes, this planet becomes another planet.

Thus, we travel from one planet to another without having to cross space.

It is just a matter of crossing time and not letting it be time that crosses us, that crosses us out, that erases us from the map.

It’s not easy, no simple thing to achieve.

And yet, I could do it.

But—not to confuse you—I’m not especially happy about that.

I didn’t choose it.

They chose me.

If there is anybody out there, please, stayed tuned.

We’ll keep reporting.

But I know that there’s nobody here and nobody out there.

There’s nothing left.

End of the World News.

And yet I—and nobody is further away from everything than I am—keep transmitting.

Ghosts, echoes, reflections, traces of voices and landscapes.

I can’t help it, it wasn’t part of any equation; yet, somehow, I remain turned on, broadcasting all shows at the same time, all episodes of all seasons, trying to find the only one that interests me.

But it’s no easy task.

There are many, too many chapters.

And the one I’m looking for is neither the most interesting nor the most successful.

But it is my favorite.

In that episode, I appear and they appear and it is just one scene. But it is, for me, the best possible scene, the most important moment of my life, of our lives.

Someday—I swear—I’ll find it, I’ll be able catch it, I’ll get to replay it.

Over and over.

Until the end of the world, until the ending of all the ends of the world.

Welcome to the ends of the world.

The first end of the world—the first of the many ends of your world, which is also, in part, my world—took place in the very instant of its beginning.

Which is to say: nothing happened.

More a Big Crack than a Big Bang

Or better yet: a Big Pfff.

Something like the snap of fingers in a dark bedroom. Just a quick pop of pure energy that found nothing to burn and feed on and grow into a raging blaze, happy to live and to burn. So, merely, an order to be disobeyed; because you simply cannot obey it, no matter how badly you want to.

Thus, the curtain that is opened or raised to reveal nothing but an empty stage without props or actors, barely illuminated by a small lamp that someone forgot and won’t even come back to find, because it doesn’t matter, because nothing matters, because it doesn’t matter to anybody: not a single ticket has been sold for this dysfunctional function that doesn’t and won’t start when all of you don’t show up.

There are no seats left because there is no theater.

The second end of this world was duly recorded. The second end of the world that I’ve heard of had at its center the small island of Santorini—Aegean Sea, about one hundred fifty kilometers from Crete—christened thusly in honor of Saint Irene of Thessaloniki, who burned, ecstatic, at the stake in the year 304 AD for refusing to renounce her Christian faith. The Greek nationalists refer to the place as Thera, in homage to the first Spartan commander to come ashore after the great disaster.

It’s approximately the year 1500 BC—I’m using, so you can understand better, this banal and inexact temporal notation—when the inhabitants of the island who didn’t refer to it as Santorini or Thera but, indistinctly as Kalliste (the most beautiful island of all the islands) or Strongili (better known as “the circular island”) wake up to a roar that seems to burst from the throat of a thousand sea lions.

The island’s volcano has opened its eye.

Some of them run to the beach and there they see it: a wave that comes rushing toward them as if driven by the love of a mother who longs to drown her children in an embrace. And the great wave drowns them and embraces them and never lets go. And not satisfied with that, the great wave completely covers the island (they’d never seen anything like this, but it’s not like they had much time to think about what a terrible marvel it was either) and then recedes in search of a new destination, and in that way goes on to sink, one by one, all the islands in the Aegean. And when it finishes with them, the wave continues on its way toward new seas and new lands and new civilizations. That wave is like a razor slitting the throat of the world from one side to the other and, somewhere, in this version of the story of History, that same wave, so many years later, keeps rolling around, always on the prowl, ready to wipe out with its foam any sign of solidity, of solid ground.

That wave is the same wave that shakes my bed night after night and turns me into a raft that someday, with any luck, will run aground and turn into an island where one solitary palm tree will grow. And there I am, writing messages like this one, waiting for the tide to bring me a bottle I can slip them into.

Here it goes, here I go.

Then—I miss my island so much—I wake up so the nightmare can continue.

The whole world is made of mud and is surrounded by the water that the ice cubes become as they melt in my glass.

Another whiskey double for me, please, and there’s nothing more unsettling than the light on in an empty kitchen, in the middle of the night, and someone rummaging through cupboards, trying to remember where she hid that bottle that now she can’t find anywhere.

The third end of this world that I’ve managed to tune in (now, all alone, I pick up glimmers of the old transmissions of ancient transmitters, of those who preceded me in this task) took place at some point during the Roman Empire.

The gods—angry or happy over one of those oh so capricious and childish matters that tend to make the gods angry or happy—descended from the heights, all together, all at once. So many gods on the surface of a planet that, weighed down by such divine weight, shifted in its orbit and got too close to the Moon and . . .

. . . forgive me, but I’m going to pour myself another drink. A long and deep drink. A drink almost as deep as my thirst and, of course, almost being the operative word here, because nobody drinks to feel satisfied. You drink to be able to keep on drinking. Everyone gets a turn (though there’s nobody left to take a turn) and here I am taking my turn, like a glove, like a costume you take off and let fall to the side at a party, in a room on the top floor, in a house that isn’t yours. And suddenly you’re cold and, so, another drink to warm you up and to keep you here a little longer, to dream more dreams of glasses full of floating ice cubes. To dream of drinking down one of those long and tall drinks in a glass made to accommodate about a fourth of the bottle.

Now I enter—soon I will enter—markets empty of people but full of bottles to empty. I empty bottles—I’ve found that alcohol lets me feel, at least for a while, that I feel nothing but what I feel—just so I, the perfect excuse, can fill them with messages that read “I empty bottles just so I, the perfect excuse, can fill them with messages and . . .”

. . . the fourth end of the world took place when the Knight Templar Enric Coriolis de Vallvidrera returned home—near the Pyrenees, on a rocky hillside, in a place where centuries later the luminous scepter of a very tall communications tower would rise—from the Crusades clutching a piece of wood that, he’d been told, originally belonged to the supposed cross that a supposed Messiah had been nailed to.

The piece of wood was, in reality, the abode of toxic and exotic spores. A virus as old as the world.

Enric de Vallvidrera falls ill—fevers and deliriums slipping through the rusted cracks of his suddenly softened and disarmed armor—and infects first his family and then the village at the base of his castle. Soon the virus is traveling in the coughs of travelers and before long, when it clings to the wings of birds and the backs of fish, the die is cast.

A disease doesn’t differentiate between the Old World and the New.

The rules of the game don’t change.

The board is the same.

And the game has ended.

And everyone loses.

The fifth end of the world . . . I don’t remember which was the fifth end of the world. Something to do with a mass suicide, with a multitude of deranged prophets.

But it doesn’t really matter anyway.

What I refer to here are the ends of the world that I’ve seen, of which I’m certain. But there are many I know nothing about, that are like a whisper at the end of a hallway of a last supper whose invitation never came, and yet, I know that it’s taking place, so near and so far.

Like an echo of an echo of an echo.

The sixth end of the world was cooked up over a low flame in the laboratories of the talented mad scientists of the Third Reich. Flashes and lightning bolts and electrodes and bubbling beakers and griffins in the form of swastikas and the scenography of sloping rooftops and, just like that, a race of supermen. Giant Aryans nearly three meters tall. Invincible soldiers.

First the Tristan series and then the Siegfried series.

And, the ones and the others, magnificent.

Spotless boots, perfect uniforms, and Cyclopes’-sized monocles that, perfectly synchronized, march on Washington D. C. and throw the wheelchair-bound President Roosevelt down the White House stairs. Soon, bored, having conquered the entire world and eliminated all the inevitably inferior races one by one, the Tristans and the Siegfrieds return from all points around the globe and march on Berlin and execute the pathetic and oh so imperfect Adolf Hitler, throwing him in a cauldron of bubbling lava.

Soon, almost immediately, there’s nothing left for them to do. And the Tristans and Siegfrieds languish and die out listening to Wagner operas in empty palaces; because the talented mad scientists of the Third Reich forgot to create Isoldes and Kriemhilds.

And this is a joke, this didn’t happen, I just happened to think it up right now and I swear if there were someone to apologize to, I’d apologize.

And even invite them to have a drink.

Two.

Three.

The seventh end of the world—and in the twentieth century, the successive ends of the world take place more and more frequently, as if the planet wanted to test all possible goodbyes, as if it didn’t know which bonbons were still in the box—took place that morning in Los Alamos, New Mexico. Trinity Site. Heavy dark sunglasses and the desert sand and the buzz of the cameras recording all of it; because man has learned how to record historical events and it’s this power to record them that, in a way, compels him to provoke them, so he can have something to record.

And so, Earth has become a dangerous place and Robert Oppenheimer and company (who know him as “Oppie” and who hear him say something about being the destroyer of worlds, something extracted from a sacred and exotic text); and the massive explosion that was thought to be controlled but wasn’t; and the joke-hypotheses of the catastrophist Enrico Fermi turned out to be true but not at all funny.

The atomic explosion ignites the nitrogen in the air and in the oceans, and the atmosphere is stripped bare like a woman tearing off her dress all at once—one of those dresses that functions more to undress than it does to dress whoever’s wearing it—after a whole night spent dancing fast and fiery dances knowing, fiercely happy, that everyone is watching her and can’t stop watching at her.

Just like they can’t stop watching that mushroom shaped cloud that climbs into the skies and grows and grows until it blots out the light of the sun with its light of a thousand suns.

The eighth and ninth end of the world are a lot alike.

An American satellite that suddenly decides to drop from the sky and that the Russians confuse for a missile coming straight at Moscow.

And that makes the rapid and ephemeral art of pressing red buttons after shouting into red telephones easy and at the same time oh so complex.

Before or after that, President John Fitzgerald Kennedy survives the assassination attempt in Dallas and reassumes his duties somewhat changed and erratic. And one night—on a guided and unscheduled visit to the Oval Office, to impress a young university student—he gives the incendiary and terminal and burning order and forgets to turn it off, to cancel it.

The tenth end of the world that I know of . . .

I should stop here to clarify that not all the ends of the world I’ve heard about (a voice describing them to me that sounds like a wind blowing in reverse, like those supposed inverted satanic messages on old LPs from back in the sixties) are so spectacular and histrionic.

There are other ends of the world—or, even though all finality implicitly carries the will and destiny to attain and obtain an end, should I say endings?—that are almost secrets: accidents, blunders, tumbles down the stairway of History.

Ends—like the previous ones—that I learned of, like I said, reviewing my operator’s files, my antenna picking up lost waves and tuning them in.

Ends suspended by the action—sometimes subtle and almost secret, other times bumbling and rushed—of those who occupied my role before me.

I didn’t meet any of them personally, but I knew their existence to be undeniable, because I couldn’t be the only one, because, half closing my eyes, I detected their presence everywhere, their secret as desperate as my own.

Like when I saw that painting that hangs now—or that once hung—in the living room of my house in Sad Songs; and more details about this coming soon.

Now, again, another of those ends of the world (ends, like I said, more private, almost domestic) shows a boy of about eight playing with one of those introductory toy sets to the marvelous world of chemistry. You know the kind: small and oh so fragile test tubes, a rudimentary microscope, a harmless burner, and multiple little beakers containing supposedly innocuous substances to which the boy adds a small piece of chewing gum, of the gum he’s chewing, combined with the reactants in his saliva and . . .

In another, a deranged rabbi, interned at a psychiatric hospital in Manhattan, discovers, after years and years of research, the exact way to reunite the loose and broken fragments of the vessel that once contained the divine presence of God and he starts to levitate, to float up into the heavens and . . . I don’t really know what happens next. The image is lost. All I know is that his story doesn’t end well, that they say he committed suicide, falling from on high, or that they threw him out a window, who knows . . .

Another one takes place at a rural airport. A passenger who has already checked his bags doesn’t appear at the gate of departure and an employee calls him over the loudspeaker—the passenger’s last name is complicated, packed full of consonants—and he reads it poorly and, without knowing it, pronounces the name of He-Who-Awaits-On-The-Other-Side-Of-All-Things-And-Whose-Name-Must-Never-Be-Pronounced because, to do so, would free him and—to the joy of Phineas Elsinore Darlingskill—he would come here from his dwelling in a golden hole in time and space to bring about an end of everything and . . .

The last of the most personal and domestic ends of the world I remember has as protagonist a man who is brushing his teeth in front of the bathroom mirror. His wife has left him, she’s taken his little daughter with her, and he’s just been fired from his job. It hasn’t been a good day. All of a sudden, the toothbrush breaks inside his mouth with a snap. Too much. He can’t take it. The man goes out onto his apartment balcony and jumps off and dies unaware that he is the person responsible for his time, that someone like him is born only every so often, and that the lives of all humanity depended on him. Around him, as the man is dying in the street, everyone starts jumping out of windows. Some of them, from lower floors throw themselves off again and again until, finally, a blow to the head brings an end to their suicidal zeal. Others throw themselves down stairways of subway stations or jump hilariously over ship rails or open the doors to airplanes in mid-flight. All of them, in one way or another, fall and fall and keep on falling. People falling from on high, people who one morning find themselves in a lawless world and, as their last and only comfort, embrace the Law of Gravity.

There’s another variation of the end of the world that is the one that, I suppose, will produce the most pleasure in readers of techno-thrillers, gun collectors, and people addicted to the insomnia of war games in which the white of day melts into the black of night and, when all is said and done, they end up inhabiting that timeless and space-less gray that is the unmistakable and mistaken color of paranoia.

This particular end-of-world scenario takes place in the final and hottest days of a Cold War that has gone on past its thaw date. The Wall hasn’t come down and now there won’t be time for it to come down and in the White House a man sighs and sweats and descends into the depths of a bunker where other men await him with tense faces and perfectly ironed uniforms and an acute agitation that they barely conceal under grave voices. Screens and files with seals that read TOP SECRET and so much information. American satellites have stopped broadcasting and are now—wounded and fallen—classified as missing in action. Satellites with supposedly clever names like OLD BLUE EYES or SPACEY LOOK or STAR STRUCK. Then, details and movements of Russian satellites that, all of a sudden, seem to have taken over the frequencies of the MIA satellites, coloring the white noise with inverted and Cyrillic letters. Satellites named VODKA or MISHKIN or TOVARICH. And the concise summary of everything that’s been happening, assimilated by the president like a movie projected in fast forward, with the supposedly fun but oh so sad rhythm of vertiginous, silent slapstick. Like one of those short films where everyone falls down and gets up and does it again just for the pleasure of running into another wall, into another cake that comes flying into their smiles.

And so, the fall of Afghanistan, the homemade atomic bomb blowing up in a Beirut apartment, the fundamentalist groups howling that Allah is great and fighting to earn the reward of heavenly virgins (because there can’t be that many virgins up there), India attacking Pakistan and Pakistan counterattacking and the sky furrowed with nuclear contrails and those red and violet sunsets so similar to the sunsets of another planet, to the colors of certain paintings.

Then, Iran launches Soviet- and American-made missiles at Iraq—or was it the other way around?—while Africa devolves into machete-blow border wars and the ground is strewn with arms and legs and heads.

Meanwhile, a group of Mexican narcotraffickers under the command of Moises Mantra, having invested a great deal of their earnings in high caliber weapons, amid blood and fire cross the border at El Paso, resolved to retake the Promised Land of Texas and California.

And an American pilot aboard a bomber decides the voice that he’s been hearing in his head for weeks—and that the pills don’t silence—is the voice of God telling him that he is the Avatar of the Last Days, and he fires on a flotilla of Russian submarines docked in the port of La Guayra, Venezuela. Several large Caribbean cruise ships disappear en route to Miami and fail to respond to calls and no one even considers the whole Bermuda Triangle thing anymore and confirmation comes in that, near Curaçao, wreckage belonging to the S. S. Sunflower has been spotted. On the round conference table the lights blink and the dates extend across the screen, and the president recalls his youth, his days of training to be an astronaut, the first time he looked down, from the surface of the Moon, at the face of this planet, ready to fall out of orbit, to be forever and irrevocably altered. The president wonders why it has fallen on him, he says to himself that maybe it would have been better not to survive the two assassination attempts, and in the end he convinces himself that there’s no turning back now. All he wants is to put an end to all of it. To rest. To rest in peace. The president breaks the seal of a metal folder and reads and types numbers and letters into a computer. Then he presses ENTER and shuts his eyes and, in a low voice, recites the prayer of a countdown.

Happy?

Had enough?

Having fun?

Want some more?

Translated by Will Vanderhyden