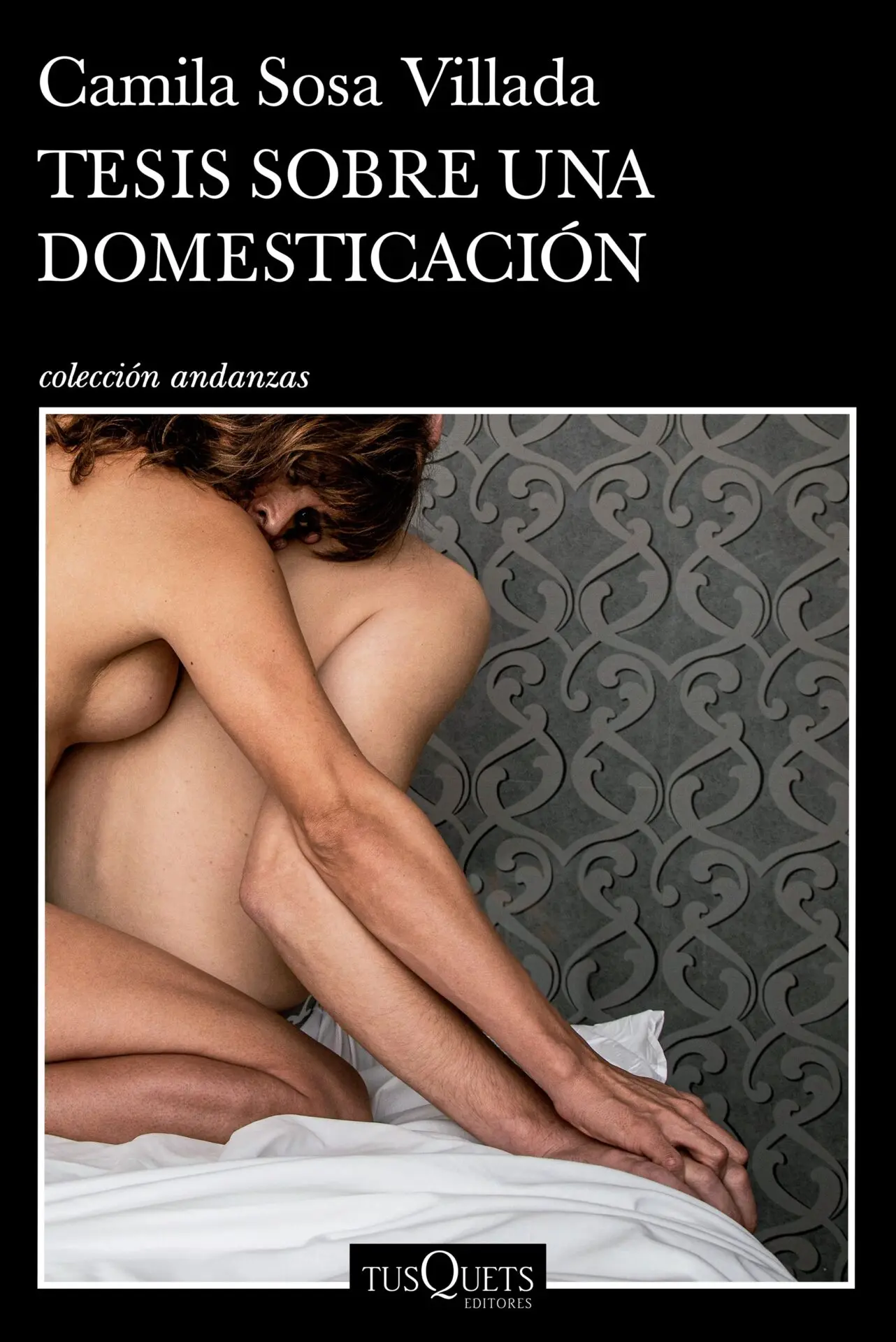

Argentine writer and actress Camila Sosa Villada, winner of the 2020 Premio Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz for Las malas (translated as Bad Girls by Kit Maude) and the 2021 Premio Finestres de Narrativa, is back with a novel in which tamed emotions struggle to break free, tender and fierce all at once, calling into question life’s façades, the familial roles we seek to play, and the acts we put on every day.

The actress has buried her past life in her happiness, and she doesn’t feel guilty about it. She has always made money with her body—once as a VIP prostitute, now as a theatre artist. Camila Sosa Villada tells us how, behind the scenes, the main character of Tesis sobre una domesticación (Tusquets) tends to scorn and ignore the whole world as a peculiar form of fondness, constantly suffering main character syndrome and badly in need of the spotlight. Sure, there was a time when she did what she wanted, how she wanted, and when she wanted, but now the travesti is married to an attorney who bores and stifles her just as he tries to tame her… lone she-wolf that she is.

With her distant, cynical mother, she walks a battlefield. She stands up to her father, ever-condescending, who lives life in shades of gray. Her son, adopted according to her husband’s decision, anchors her to tenderness. The actress has twisted the attorney’s life, and her hormone-treated body has forever disrupted the patterns of the man’s desire, since “one single travesti is enough to undermine a house’s foundations, to untie the knots of a commitment, to break a promise, to give up a life.” The actress knows that, in the end, whether tamed or not, “flesh rots the same as all living things on this earth.”

Natalia Consuegra & Juan Camilo Rincón: In the book’s first paragraphs, Valeria Vegas talks about theatre backdrops as a trap. What is the worst trap an actress can fall into?

Camila Sosa Villada: You know how there are actresses who never stop working? They make one movie after another and so on. I’m not that way; I need a little more time to get into and out of a character. So I think one of the biggest traps is directors. Another trap is thinking you can make a living from this profession (laughs). I think it’s better to live off something else and do what you want when you want. For example, I have friends who do up to four plays per week. The way I see it, that’s a job for martyrs, and I don’t think it’s right to sacrifice your life for a job.

N.C. & J.C.R.: Speaking of directors, at one point you say the actress ceases to be Cocteau’s madwoman. To what extent does an actress belong to a director?

C.S.V.: No, you belong to a character. There are actresses who end up belonging to a director because said directors are very cunning and manipulative—as you can see, I’m somewhat resentful of directors. Actresses don’t belong to directors, they belong to whomever created the character. Sometimes they belong a little to the author and sometimes they belong a little to themselves; sometimes they are just themselves, as has been the case for me in some theatre productions I’ve done. When I say she ceases to be Cocteau’s madwoman, I mean it inasmuch as the character is a woman who is mad, but still, she ends up wrecking the home, just as she does at the theatre.

N.C. & J.C.R.: You talk about the contrast between the luxury at the top and the dampness of the basement, which is, in the end, a metaphor for life in general. How does this contrast work in theatre life? We have the sparkling show up there, in contrast to what’s “below,” the off-stage reality.

C.S.V.: The stage is a rather miserable place either way, you know? It’s rare to find a theatre in good repair; they’re always quite run-down and dingy, the dressing rooms, the floors are full of splinters, even in big, important theatres like the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires; the dancers used to complain about the splinters in the boards. There’s not so much contrast between reality and misery in the theatre; both are miserable places, and that’s why they’re nice places too. That’s why you’ll sometimes give up your life and your health for it, above all, because they end up being places that remind you of yourself, of your miserable self.

N.C. & J.C.R.: Fans await the actress “to see who she is when she’s not acting.” That’s a really beautiful idea: getting to know the person behind the actress, how she sees the world when she’s not onstage, after the performance.

C.S.V.: That part’s awful. I feel completely vulnerable because there’s something else about the theatre, that way it has of somehow protecting you. You call on your saints, your dead loved ones, whatever beings you believe in, and there’s something about it that shields you; once you’re off, you’re alone, you are yourself, and they see you for what you are. Luckily, I’ve never been particularly vain in my acting; generally speaking, I prefer to be ugly rather than pretty, but I imagine all the actresses who have built their careers off being attractive have to stay mysterious, have to disappear, come out with a veil and dark glasses on. They have to learn to be that way. The question of how the world is when she’s not in it comes from the fact that she’s used to being the main character, to the world turning around her.

N.C. & J.C.R.: And you put it well: “main character syndrome.” It’s a question of how the world works, what people are doing when she’s not there.

C.S.V.: Look, my dad used to say, “In this house, nothing works if I’m not here; work with me. If I’m not here, everything falls apart.” My mom, on the other hand, would say, “If I’m not in this house, nothing gets done, nothing gets cleaned…” I think we all suffer from a little bit of main character syndrome, from believing the world stops turning without us. It also has to do with a somewhat anthropocentric way of thinking, I believe. It comes down first to egotism, but also to the idea that human beings make the world go around, when in fact all they do is slow it down. When the fires were happening in the Amazon, and people were crying over the trees and animals, a friend of mine who’s an environmental journalist told me the Amazon was formed by human beings, who had come there in the Ice Ages, bringing seeds on their feet; that is to say, human beings change the climate for themselves. All species do, not just us, but at any rate, we tend to believe we are the masters of the world.

N.C. & J.C.R.: Recently you were speaking about your parents, and in the novel there’s a clear difference between the idea of the home and the idea of the family, though we tend to think they’re one and the same.

C.S.V.: That has something to do with the fact that it’s the lawyer who has these ideas stuck in his head. There comes a time when she loses her sovereignty over her decisions because she’s somewhat seduced by him, because she’s in love with him and love has always been a tool by which women, especially, get lost in the family, in responsibilities, in commitments. But that’s his deal; it belongs to him and to his class. She is much freer, and her mom has always known it. She tells her something like, “I told you not to get married; being alone really suited you.” I think it’s his problem more than it is hers. I love the actress, I’m totally indulgent toward her. The narrator may judge her a little, but I love her very much. Out of all the characters I’ve written, I like her the best.

N.C. & J.C.R.: There are some short snippets where the actress speaks in the first person, and then there’s her mother’s monologue, and her father’s. Where did that narrative decision come from?

C.S.V.: I argued about it a lot with my editors because they didn’t like the italics. I really had to fight for it. My editor in France told me it was a battle that needed fighting, because he thought that was the best part of the book, when the actress speaks. I said to him, the fact is, it’s a thesis: the narrator has her cell phone with testimony from the actress before she was killed, so the narrator transcribes it. I really like that about the book. There are two versions of this book: the first is from December of 2019. I wrote the novel in six months but I didn’t want it to come out; I talked to the editor and told her, “We’re making a mistake, this book shouldn’t be released.” It struck me as very pornographic, something that could never exist in the real world. So I decided to rewrite it. The book still starts and ends the same way, the characters are all exactly the same, there are no new characters, and I didn’t change anything about the book’s composition, but I did dig deeper into some things regarding the director’s relationship with the actress, the actress’s relationship with her half-brother, and the actress’s relationship with herself. That’s where I got the idea to turn it into testimony. They told me, “We can make it dialogue or it can go straight into the third person.” I said, “No! Because you have to hear her speak, not arguing with the husband, saying one thing or another, but listening to her reflect on her existence.”

N.C. & J.C.R.: One of the novel’s most valuable aspects is how it guides us through the general idea of domestication, of being tamed, and we gradually realize how this process is happening to us all.

C.S.V.: You know, they say human beings didn’t domesticate dogs, but rather dogs domesticated human beings. There’s a lovely book, Pigs: A Portrait by Thomas Macho, that talks about the domestication of pigs. He says they used to live in forests, and then they lived free in towns, wandering through the streets until they started being put in pens; one of the most important tools is being able to keep a species locked up. That’s why foxes and flying birds can’t be domesticated; only animals that can be enclosed can be domesticated.

N.C. & J.C.R.: You’ve spoken about gender transition as a metamorphosis, as an uprooting, as a departure. How have you dealt with it in your fiction?

C.S.V.: In Las malas, I say to cross-dress is always to depart. And, well, I mean it literally. You have to know how to leave places. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake says, “Expect poison from the standing water.” You have to know how to leave, you have to know how to change, you have to know how to change your skin. When I was a kid, I lived in the country with my mom—I think I talk about this in El viaje inútil, too—and the snakes used to shed their skin by our front door. That image was always very powerful to me, opening the door in the morning and finding an empty skin, a whole snake with no flesh inside. It looks almost like a snake made of paper, a clear snake, a glass snake. That was very important to me. I don’t think you always have to be the same person, or the same thing, or in the same place. Marrying yourself to an identity is alway a prison sentence, a domestication. I say the same thing in my new book, La traición de mi lengua, about identity as a prison. And I believe it.