Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from the chapter “Under Western Eyes: Visiting Friends & Artists” of Chakravarty’s forthcoming book, The Tree Within: Octavio Paz and India, Penguin Random House, 2025. It is published here with permission from Penguin Random House India.

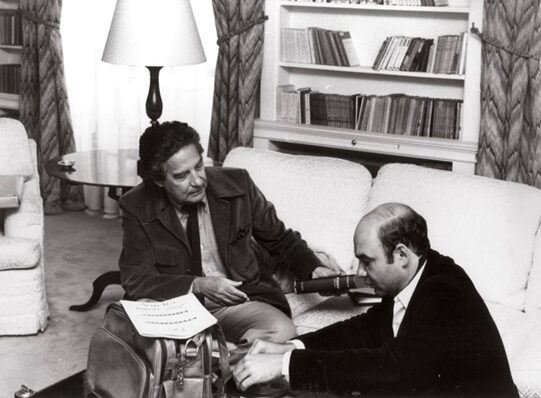

Among his Latin American contemporaries to whom Octavio Paz transmitted his passion for India was the Cuban writer, Severo Sarduy (1937–1993). Paz nurtured him, one of the most outrageous and baroque of the Latin American boom writers, into the world of India’s meditative exploration, which left a deep impact on Sarduy’s works. “Octavio Paz gave me India, the most extraordinary gift that anyone can give,” he wrote. Spurned by his own country for his homosexual themes, Sarduy repudiated the revolution and lived in exile in Paris, never returning to Cuba. He met Paz after his return from India following his resignation in 1968 when he spent some time in Paris composing renga in collaboration with Charles Tomlinson (one his English translators) and two other poets at the basement of the Hotel Saint-Simon. Sarduy met Paz through a common writer-friend at the hotel’s basement, which had become a hub of poets.

Sarduy, like most people, could never forget his first meeting with him. When he asked him about India, Paz told him that it is a culture that dissolved the binary oppositions which the Western mind grows up with: heaven and earth, matter and spirit, body and soul, life and death, sex and religion. (The latter was indeed the cause of Jung’s nervous collapse during his visit to India.)

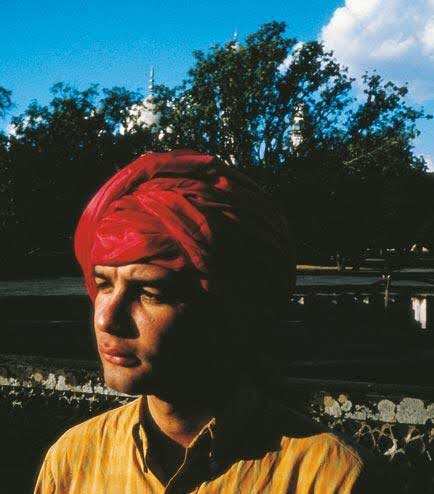

Sarduy read and re-read Paz’s essays in Conjunctions and Disjunctions (1969) to which he paid a tribute by using it on the cover of his own novel, Cobra (1972). First in 1971 and later in 1978, Severo Sarduy travelled extensively across Asia (“el Oriente”), centred around India. His appetite was continually whetted by the Mexican writer:

Without Octavio’s words and without his texts, I would perhaps never have travelled there. Or I would have gone the way others go, attentive only to the external details. Since India is not just a continent but also an enigma, at times a riddle, it is a constant challenge to perception, and to life. It asks questions to which the “barbarian” must find compelling answers.1

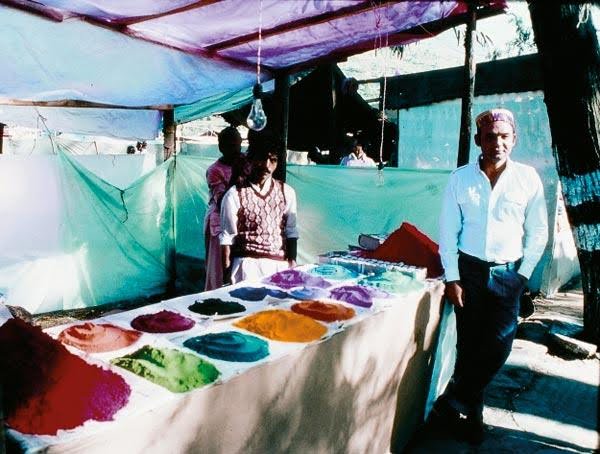

Sarduy walked along the banks of the Ganges and the streets of New Delhi, fascinated with the art, mythology, religious practices, intoxicated by smells, colours and flavours. He engaged in long conversations with Buddhist monks in the Himalayas and in Ceylon (Sri Lanka now). The final chapter of Cobra, titled “Indian Diary,” bears literary testimony to his experience. His novel Maitreya (1978) opens in Tibet, but the character in search of a messiah travels to Cuba and the United States, then ends up in Iran. In Cobra, the protagonist is a transvestite. Sarduy, being gay, positioned the transvestite as a metaphysical proposition with reference to a culture that celebrates the androgynous self. The metamorphosis of genders haunts most of his works.

Sarduy’s homosexuality and literary or figurative transvestism may have been the reason why Paz’s conversations with him revolved around these themes. He pointed out that while there were no homosexual gods, male or female, in Hinduism, gay and lesbian characters appear frequently in Greek mythology. This may have been due to the central archetype in Western culture, which is masculine:

Compare Christ with Buddha. Christ is made of straight lines, there is not a single curved feminine form in him. No wonder Christianity has also been the religion of the Crusades, the Inquisition and capitalism. Islam, the religion of the sword, is also predominantly masculine. On the other hand, in the figure of Buddha and Shiva we find a certain femininity that is integrated into their virility. Indian goddesses are the epitome of the feminine—round and wide hips, huge breasts—and yet they ride tigers and lions, fight monsters: they are virile warriors [like Durga]. In India there was an interpenetration between virility and femininity. We should aspire to be more feminine men and more masculine women. The drama of American feminism is that its archetype is masculine.2

While supporting the rising power and voice of women in the seventies, Paz was critical of how the genders were reshaping themselves: women were being deformed and men mutilated.

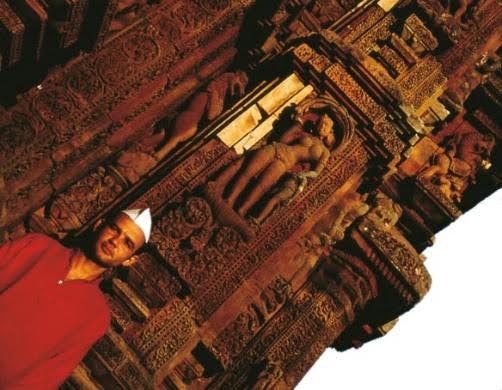

Perhaps under Paz’s influence, Sarduy felt increasingly drawn to the “feminine masculinity” of Buddha. At Sanchi, a few kilometres away from Varanasi, where the Buddha gave his first sermon, Sarduy wrote:

There is nothing permanent or true,

nor oblivious to deterioration and old age.

What is, dissolves into what is not,

and in the iris all that you see…3

Apart from poetry, a major connection between Paz and Sarduy was their common interest in the structuralist movement. Sarduy was the only Latin American associated closely with the journal Tel Quel, which disseminated structuralist ideas and experimental writing. He was a close friend of one of its leading figures, the French intellectual star, Roland Barthes, with whom he travelled across Morocco. Paz too was clearly under their spell from the mid-fifties till the seventies, and that interest was reflected in several essays he wrote during his India-years.

Any critical thinking that fostered artistic creation enthused Paz. Not otherwise. He adored surrealism and dadaism but despised existentialism. “Where is existentialist painting, existentialist poetry, sculpture?” he would ask Sarduy. When Barthes’ Writing Degree Zero was published in 1953, or Mythologies came out soon thereafter, Paz was captivated by his thinking. He dedicated one of his poems to Roman Jakobson, the Russian pioneer of structural linguistics who had a seminal influence on Barthes and Lévi-Strauss. Paz discovered Jakobson through Lévi-Strauss, on whom he wrote a book in 1967 titled Claude Lévi-Strauss o el nuevo festín del Esopo (literally, “Lévi-Strauss or the New Feast of Aesop,” but the English translation is called Claude Lévi-Strauss: An Introduction).

Jakobson had argued that poetry successfully combines and integrates form and function; it turns the poetry of grammar into the grammar of poetry, so to speak. His insights inspired Paz to reflect upon the use of language in poetry and in translation:

Between what I see and what I say,

between what I say and what I keep silent,

between what I keep silent and what I dream,

between what I dream and what I forget:

poetry.

It slips

Between yes and no,

says

what I keep silent,

keeps silent

what I say,

dreams

what I forget.

It is not speech:

it is an act.

It is an act

of speech.4

Paz thus gave poetic form to structuralist thinking about language, speech and writing. A brief poem, “Homage to Claudius Ptolemy,” acknowledges that even as one speaks, one is spoken. It was one of his personal favourites that he recited during his Nobel acceptance speech, a poem written in a dark night in the open field when he realised an unspoken correspondence between stars in the sky and the individual on earth:

I am a man: little do I last

and the night is enormous.

But I look up:

the stars write.

Unknowing I understand:

I too am written,

and at this very moment

someone spells me out.5

Paz continued to explore structuralist ideas in his theory of poetry elaborated in Signos en rotación (“Rotating Signs”) about how poetry searches for “ceaselessly elusive meaning.”

“Where is the Orient?” Barthes had once asked his friend Severo Sarduy after returning from a trip to Japan. Sarduy in turn posited the same question to Paz. It would be a mistake to believe that the “Orient” is a place far away from us, Paz told him.

The popular interest in Buddhism and other Oriental religions and doctrines betrays the same sense of deprivation and the same appetite. It would be a mistake to believe that we are looking to Buddhism for a truth that is foreign to our tradition: what we are seeking is a confirmation of a truth we already know. The new attitude is not a result of a new knowledge of Eastern doctrines, but a result of our own history. No one ever learns a truth from outside: each person must think it through and experience it for himself.6

Paz thus suggested to Sarduy that the “Orient” was not just out there, but within us. To reach it, the Latin American writer needs to overcome the imposed binary mode of Western thought. The questions he poses underlie the deepest part of our being.

Notes:

1 Guerreo, Gustavo & Xosé Luis García Canido (2008), p. 240.

2 Guibert, Rita (1973). OC, vol. VIII, p. 1056.

3 Palabras del Buda en Sarnath/“Words of the Buddha at Sarnath,” 1991.

4 Gavilla/“Sheaf,” tr. Eliot Weinberger.

5 Hermandad/“Brotherhood,” tr. Eliot Weinberger.

6 Alternating Current: 102, tr. Helen Lane.