In Mother Archive: A Dominican Family Memoir (published by the University of Iowa Press in October 2024), writer and photographer Erika Morillo explores the connections between personal and political history. Her father disappeared in the Dominican Republic under the regime of Joaquín Balaguer, Rafael Trujillo’s successor. Shortly after the murder, her mother rid the house of all images of her deceased husband. Morillo’s mother also cuts herself out of photographs and is largely absent in the author’s life. Mother Archive is a reconstruction through text and image, a form of addressing the erasures in Morillo’s life.

The book covers a vast amount of territory—both geographic (the Dominican Republic, Chile, and the United States) as well as thematic. Morillo reflects on immigration, generational trauma, and healing. Motherhood is, as the title suggests, a dominant thread. It refers to homeland, to Morillo’s mother, and to the author’s own transition to motherhood. In one chapter, Morillo describes her own pregnant body as a “vessel,” a word that implies the ability to conduct or transport material. Mother Archive is a bridge between generations, between Morillo’s parents, “the children of long and bloody dictatorships,” and her son, who was born “free of this baggage.”

Victoria Livingstone: Throughout the book, you tie your family’s history to the larger history of the Dominican Republic. How did you navigate balancing political history and family history? Can you say more about your research process?

Erika Morillo: In writing this book, the political landscape in which my family’s history and my upbringing unfolded was of vital importance. In great part, this work is an attempt to understand the lacunae in my memory and to give a sense of order to the information I’ve collected from family members willing to share. The hard evidence of the oppressive regimes of Trujillo and Balaguer—which has been widely researched and documented—helped to counter the elusive nature of my recollections.

I did extensive research online and in books, asked family members for photos and videos, interviewed people, and collaborated with another artist to help me research the national archive in the Dominican Republic. In these archives, I found evidence of the horrors of these dictatorships, of other families whose relatives had been taken from them and disappeared. I found, in my own story, a larger societal pattern, a collective history.

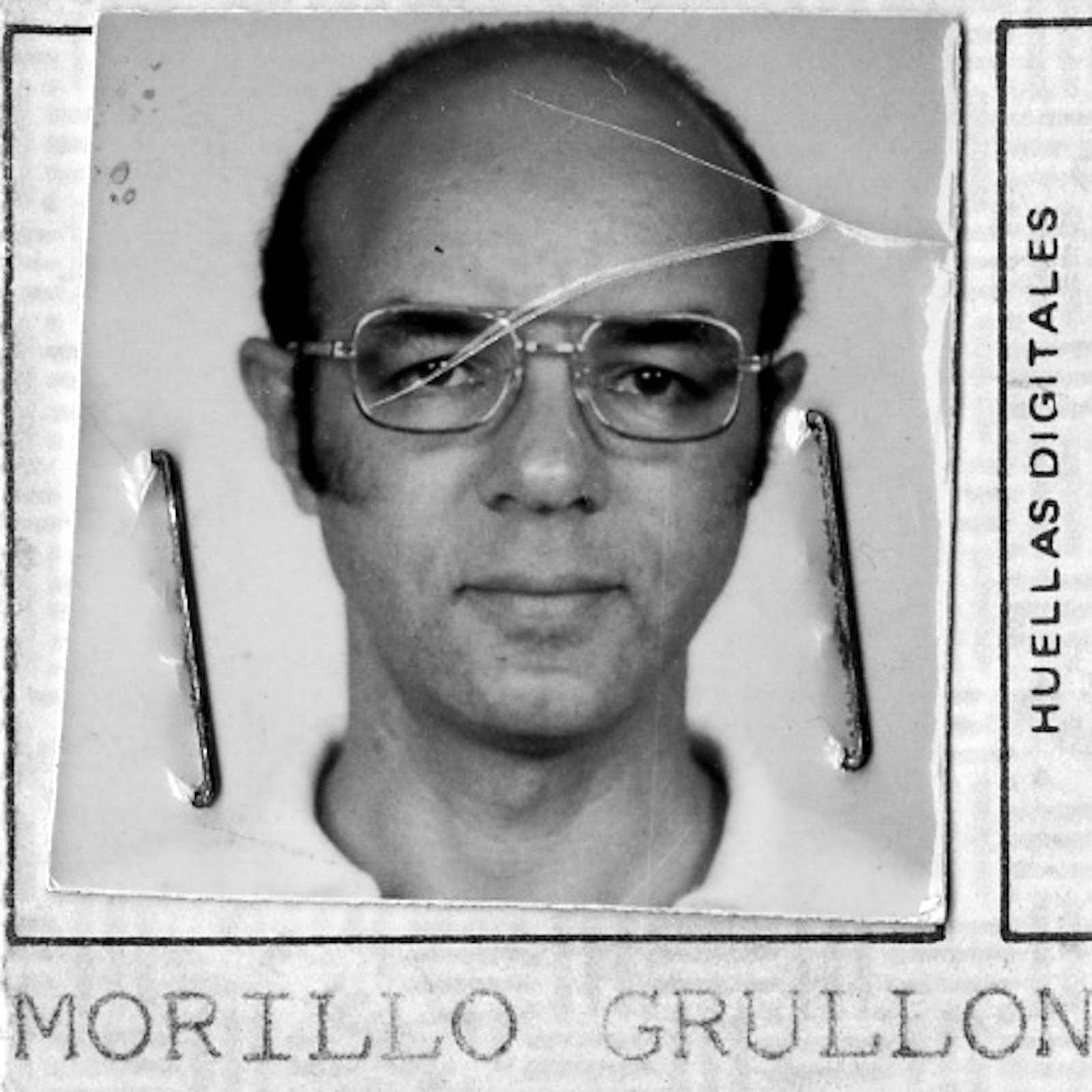

I also found images. Photographs of my mother over the course of six decades; images of me as a child at home with my siblings while being interviewed by the media; film stills of my mother and me on TV denouncing my father’s disappearance; the headshot of my father used in all the newspapers, looking straight at me through the screen; digitized article after digitized article. I looked straight into his eyes and still could not remember him. Doing research for this project validated my experience, but also—by collecting information obsessively from a myriad of sources—complicated its telling.

V.L.: You are a photographer. You write that you started photographing your family in part to reverse your mother’s “systematic erasing of [your] family history.” How else do you see the interplay between text and image? What can photography do that text cannot, and vice versa?

E.M.: Only in hindsight, while writing this book, did I realize that the photographs I was taking served a deeper, more subconscious purpose than documenting the reality in front of me. When I gathered all the photos I’ve taken and collected for this work, I realized the accumulation of them, this archive I’ve built, was the direct opposite of what my mother did when she disposed of all our family’s photographs.

Photographing is a hunger; a desire to participate in my own experience. A way to kill the silence that was so pervasive throughout my childhood. I see these images as a tool to understand my thinking and my sensibility. To discover what matters to me and what I am lacking. They are the springboard for clarifying what I want to say in my writing.

In Mother Archive, I think the writing is complicated—and thus strengthened—by the images. They embody the push and pull of collecting and discarding, symbolizing the tension and ambivalence in my relationship with my mother.

V.L.: You do not caption your photographs in the book, but there is a clear connection between text and image. I am interested in this photograph that follows a description of your mother’s “pervasive absence” and the instability it caused in your life:

V.L.: Could you say more about this image and the surrounding text? And about the interplay between text and image in the book in general?

E.M.: While writing the book and working with the photographic archive I gathered, I tried different photo experiments. I did not want to rely so heavily on family photos from the past, but rather find a way to make new images based on them, to add another layer of meaning to this archive. I dipped photos in honey, made large prints of these photos and plastered a whole wall in my home, projected photos on the walls, and made self-portraits alongside my mother this way, indirectly.

That image happened by accident, as I was testing my camera’s shutter speed (in preparation for making a self-portrait) and placed my hand in front of the photo projection on the wall. I was struck by the resulting image: the hand that, as it reaches for the mother, grasps only a void. And the more it reaches, the more elusive the mother becomes. My intention behind these images in the book—including the recent self-portraits I took with my mother at her home in Florida (below)—are all an attempt to get close to her, to stage the bond I wish existed between us in real life. The text surrounding this image speaks of these frustrated attempts at closeness.

V.L.: What about your process? Do you begin with text or image?

E.M.: Most of the time, it is an image—or lack thereof—that inspires the writing. In this work, the variety of images—from various periods and sources, and in different formats—provided many different entry points for the text. In a way, they informed its chronological displacement; I would look at a recent portrait I made of my mother and compare it to portraits from her youth. Other times, the writing came to fill in the gaps of time in this photo archive by recounting, speculating, or imagining.

V.L.: This text is so richly textured—and not just in terms of text and image. Your prose is highly sensorial in other ways too. In one chapter, you reflect on what can happen in two seconds, “[the time] it takes to hit someone with the butt of a gun and leave him unconscious [your father’s murder]… Two seconds. I replace the blow with the sound of Papi’s sneeze, with a sprinkling of sugar over my grapefruit, his way of getting me to eat it. Two seconds. Fat drops of tropical rain filling my inflatable plastic pool in our backyard, the clean slash of his machete cutting through coconut husk before turning it upside down to fill my glass, white speckles of coconut meat floating in the cloudy water.” Can you say more about your process reconstructing these memories, and the emotional weight of doing so?

E.M.: There is such absurdity in unexpected death. At first, you try to make sense of it by asking questions that often lack answers: Why did this happen to our family? Why him? How did they kill him? In my case, since I was only five when my father disappeared and because my mother dealt with her grief by never mentioning him again, my young mind skipped the questions and severed him from my memory. During my childhood, I think this served a purpose. It shielded me from indescribable pain that might have undone me. But, as an adult, this void filled me with anxiety, and my frustrated attempts to remember my father only led to a sense of powerlessness.

Reconstructing these memories out of that void and through this archive, part-documentary and part-imagined, gave me agency. These images—how I picture my father, how I imagine him from what others told me and from what, at times, seeps into my brain—quell that part of me that is endlessly seeking. This is how I make sense of the absurdity.

V.L.: I am very interested in the decisions you make about language. Your first language is Spanish, but you write in English. You mention that, in English, your mother’s words “lose their teeth.” You also say that English is a form of “self-exile.” However, you also leave many words and phrases untranslated in Spanish. Could you say more about your decisions about language?

E.M.: Writing the book in English—and deciding to write solely in English for all my work—is a way to create distance and space from my experience growing up in the Dominican Republic, from my upbringing. I initially tried writing this book in Spanish, and I felt a disconnect to my mother tongue and to my voice reading the writing aloud. It is not a coincidence that, when I lived in la isla, I had issues standing up for myself, expressing my feelings, and finding my anger when it was necessary and purposeful. In Spanish, I had no voice and no practice with which to understand and articulate my experience. This kind of endeavor was discouraged constantly and severely in my family.

Conversely, in my current life, English is new territory; the language of other possible worlds, a tongue free of emotional memory for me. My English was very mediocre when I moved to the United States two decades ago, and it has been one of the most joyful experiences to learn this new language by filling small notebooks with new words as I discover them. When I remember in Spanish, there is a lump in my throat. My words are stuck in the never-ending cycle of the past. In English, I am able to articulate my experience so much more eloquently, using words and sounds that were never spoken to me in my family, words that, at the brief moment of writing, are mine and mine only and cannot be taken away from me.

The inclusion of the Spanish words, this Spanglish, for me speaks directly to the space in my memory I want to give to the place where I come from, to my lineage. I want to acknowledge my roots, to give evidence that they shaped me, but not allow them to dictate all that I am.

V.L.: Much of this book is written in the second person, addressed to your mother. Often the second person is a way for writers to gain distance from events described, but that does not seem to be the case here. Can you say more about the decision to address the book to your mother?

E.M.: I think the second-person address in the book was not about creating distance—quite the contrary. It was purely confrontational, and at times coaxing.

This book is addressed to my mother, yet she is not its audience. I find these contradictions really fruitful for talking about the inner workings of our relationship, how we give something only to take it back, how when we truly face each other, we can’t stomach what we see. I wanted this epistolary form written in English, a language my mother doesn’t speak, to represent those dynamics.

V.L.: A major theme in the book is your mother’s harshness and neglect. You write that she is like “the third rail beneath [your feet], always vibrating with lethal electricity.” Your mother is still alive. Were you worried about writing about her and revealing the trauma of your upbringing? What are your thoughts on the ethics of memoir regarding writing about living people?

E.M.: I went through a wide range of emotions while making this work. Guilt and shame were always at the forefront. Shame for exposing the dysfunctional environment that made me, and the shortcomings I see in myself as a result. But guilt has been the toughest emotion to contend with. It is because of this guilt that the name of each family member in the book is reduced to only a letter. My mother and her siblings—especially her sisters, the women in my maternal family—had never faced what happened to them as children. They never spoke or processed that my grandmother, their mother, was a victim of femicide at the hands of her husband, their father. This horror, so hermetically preserved, hardened them as women in their lives, especially in their motherhood. This festering wound turned into anger and violence towards their children.

While I was writing and researching, the women in my maternal family were angry and constantly reminded me that this was not my story to tell. How dare I expose our family’s tragedy for the world to see? But the subtext, what I read between their words, was “This is our fault; we are damaged goods,” a feeling I know so well because, unexamined, it had been passed on to me.

When I look at my son and recognize my upbringing coming up in my own parenting, the only thing that helps me do right by him is this work, this time spent in front of an empty page making sense of my family history so as not to repeat it. Writing this memoir wasn’t frivolous; it was not an endeavor for art’s sake. It was about survival and cutting the link with a painful past. These are the ethics behind my work, and I am at peace with them.

V.L.: What about your son? The book is addressed to your mother, but your son was your first reader. How did his feedback shape your writing? Did you feel you were writing partly for him? Do you have an ideal reader in mind?

E.M.: My son is a very close reader, and I trust his instinct and grasp of narrative. Sharing the writing with him as chapters came to life was, in part, about finding which parts were not engaging, or too dreamy or abstract. Since English is his first language and I still write at times with a Spanish syntax at the forefront, his feedback was really helpful in ensuring clarity and sticking to the point.

I did not write the book for him, but as he read the work, he was also learning details about our family for the first time, about his grandparents and great-grandparents, and also about his mother. He asked questions, but I never sensed my hunger “to know and understand” in him. I sensed that he was curious but already at peace with this new information.

My ideal reader is curious and unafraid of experimental forms, someone who is inclined to do their own research when they are unfamiliar with the language or culture described. A reader who is moved by form and language as much as the story being told.

Main photo from Mother Archive: A Dominican Family Memoir (Erika Morillo, 2024).

Erika Morillo

Erika Morillo